There are many legislations and policies today in Canada. Arguably, the most important are the: Royal Proclamation 1763, Indian Act 1876, Immigration Act 1910, and Multiculturalism Act 1989. In this blog I choose to focus on the Royal Proclamation, the one that started it all.

There are many legislations and policies today in Canada. Arguably, the most important are the: Royal Proclamation 1763, Indian Act 1876, Immigration Act 1910, and Multiculturalism Act 1989. In this blog I choose to focus on the Royal Proclamation, the one that started it all.

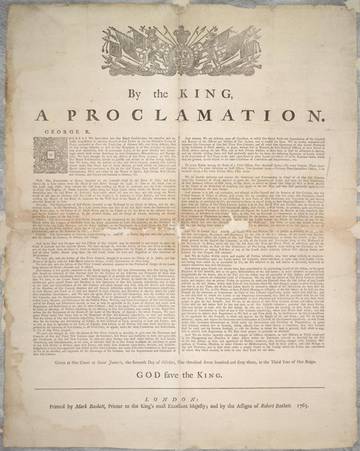

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 is a document issued by King George III to “officially” claim British territory in North America after Britain won the Seven Years War. This document set out guidelines for European settlement of Aboriginal territories. Regardless of King George’s claim to North America, the Royal Proclamation explicitly states that all land would be considered Aboriginal land until ceded by treaty. Settlers were prohibited from claiming land from Aboriginal occupants. The only way a settler could claim land was through purchasing said land from the Crown, who were the only ones able to buy land from the Natives.

The Royal Proclamation was an important first step towards the recognition of existing Aboriginal rights and title. Once the Proclamation was introduced, it set a foundation for the process of establishing treaties. The good intentions were initially there, however what was to come in the later years was unimaginable.

Despite the British consideration for Aboriginal rights and title, the Royal Proclamation was premeditated and written by British colonists. There was no Aboriginal input, and it clearly establishes control over Aboriginal lands by the British Crown. Regardless of having preexisting inhabitants, both the French and British tried to claim Canada as their own with little or no thought or consideration to the Natives.

Is the Royal Proclamation still valid? At the same time: yes and no. Since technically there is no law that has overruled the Proclamation, it is indeed still valid in Canada.

The Proclamation applied to all of North America, including the United States. Since American independence from Great Britain, the Revolutionary War rendered the Proclamation no longer applicable. However, the United States created its own similar law in the Indian Intercourse Acts.

One author that can correlate to the Royal Proclamation is Daniel Coleman; he offers us a term deemed “fictive ethnicity,” in his White Civility: The Literary Project of English Canada, which is defined as the British whiteness in English Canada, both in the past and future (6-7). He goes on to argue that this British whiteness still occupies the position of normalcy and privilege in Canada.

One author that can correlate to the Royal Proclamation is Daniel Coleman; he offers us a term deemed “fictive ethnicity,” in his White Civility: The Literary Project of English Canada, which is defined as the British whiteness in English Canada, both in the past and future (6-7). He goes on to argue that this British whiteness still occupies the position of normalcy and privilege in Canada.

He also suggests that beginning with the colonials and early nation-builders there has been a “literary endeavor” to “formulate and elaborate a specific form of [Canadian] whiteness based on the British model of civility” (5). Coleman argues that British whiteness is a “fictive ethnicity” that still occupies normalcy and privilege in Canada today (7). One example, the British Commonwealth. Canada is still a part of it and we still have Queen Elizabeth II as our queen (even though she has no authority). The Royal Proclamation supports Coleman’s statements.

How did the normative concept of English Canadianness as white and civil come to be constructed in the first place? Over a long period of time, with European-centric ideas and mass genocide. Our nation seems to have forgotten the very uncivil acts of colonialism and nation-building. There is a quote that I find completely applicable to this blindness: “ignorance is bliss.”

———————————————————————————————————————-

———————————————————————————————————————-

http://www.ammsa.com/publications/windspeaker/map-maker-provides-pre-contact-look-canada

https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1370355181092/1370355203645

You make some good and important points here – and indeed, it is the Royal Proclamation of 1763 which is foundational to protecting the rights of territory for the First Nations and Inuit who have not ceded their land to the crown via treaties. Exactly right, thank you.

Hey Kayla,

I actually grew up outside of Canada, so a lot of this was new information to me, and I found it both incredibly interesting and useful.

Some of this made me think of the introduction to Frye’s The Bush Gardens, in which Linda Hutcheon states the Frye’s view of Canada as “initially less a society than ‘a place to look for things'” (xvi), which completely erases the existence of any peoples prior to the arrival of the white settlers. Canada was judged by its usefulness to white colonists, and not as a land in which people were already living and belonging.