There is so much I learned from our experiences in Steveston. There’s something about being outside, feeling the cool air, and seeing the river delta so connected to the histories and peoples here that engages a more complete way of learning, and a more full part of myself, than what I usually experience in a classroom setting. While my experiences there were larger than one essay, this reflection brings together some of the connections, feelings, and highlights from that day.

Race and discrimination

One of the themes that struck me during our time in Steveston is the layers of racism and discrimination that are a huge part of its context. Throughout most of Steveston’s settler history (Indigenous peoples have been living in the region for thousands of years), work was separated based on gender and perceived race. White women could have certain jobs while Chinese men could have other jobs; pay was largely based on one’s job and thus, race and gender. Local discrimination and segregation impacted who fished in the community, where people worked, who was paid for their work, and what options and opportunities one had. I imagine that this context might have been similar along the B.C. coast and I wonder what kinds of legacies or ongoing patterns of racism and discrimination are still being felt today and how to change these (e.g. the often unpaid work that many women do was something that came-up as a current pattern).

I was also struck by the impact of Japanese internment (1940s) on the Japanese-Canadian and other Steveston community members. Around two-thirds of Steveston residents were of Japanese descent before internment, including all boat makers and many of the business owners. Most of the interned Japanese-Canadians never returned to Steveston, partially because their assets (e.g. boats) had been auctioned off by the government (there was little to return to) and partially because there was a two year ban on their return to the area after internment ended (resulting in many people settling elsewhere in that time).

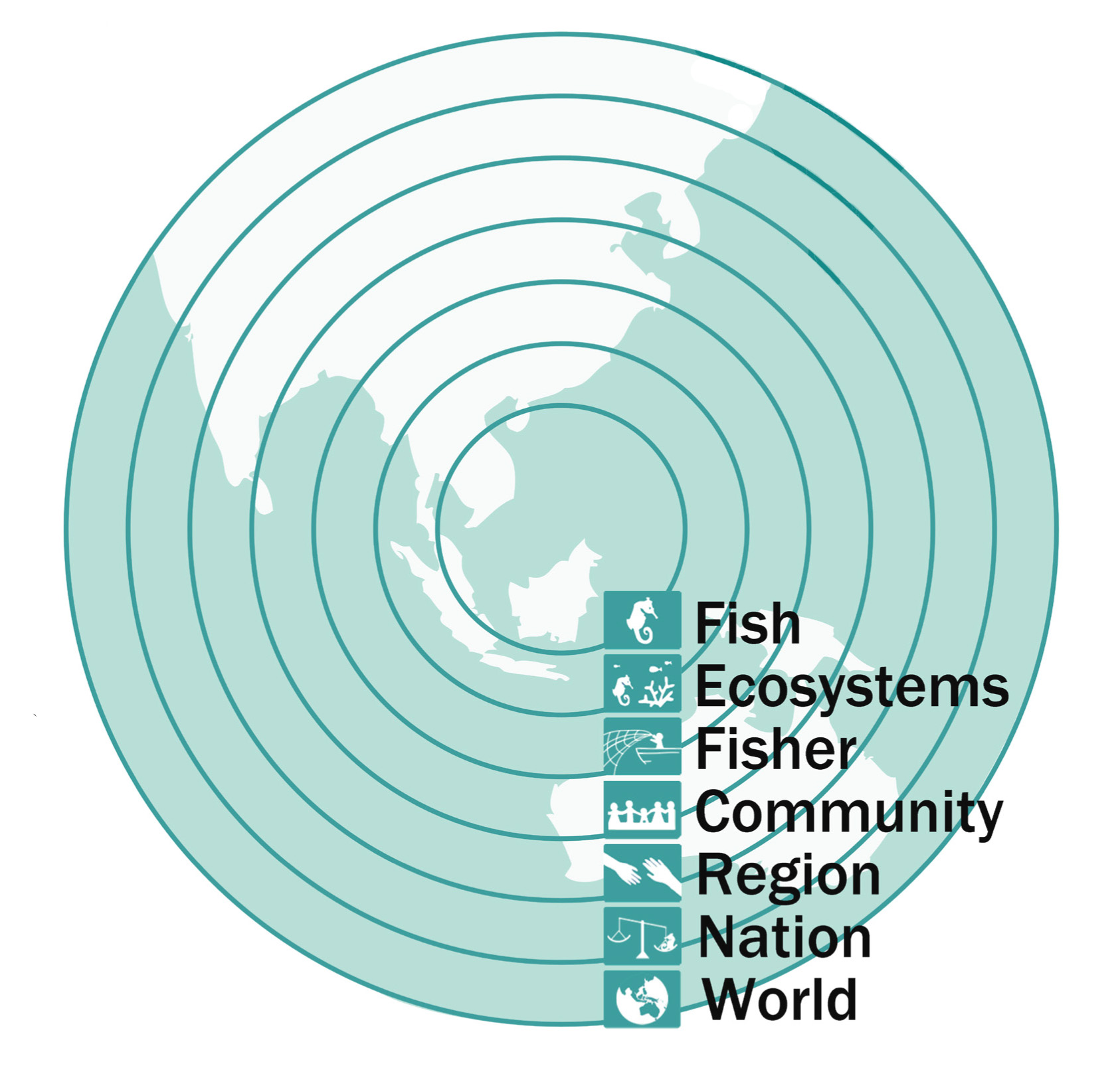

Within our class themes, this racial and gender discrimination can be tied into the onion world model — with fishers being impacted by broader community and government policies and actions. For instance, Chinese workers in the early 1900s, had little choice in what they did for work or how they were paid, especially as they were required by racist government policies to pay a hefty head tax (up to 500$). While this may seem like a social and moral problem, this reminds me of how these broader layers of communities and governments impact conservation options and individuals. For these Chinese men, the head tax debt and other forms of racism limited where they could work, resulting in them having few choices in what they could do or where they could go at the time. Similarly, as mentioned in lecture, people relying on the oceans may have few opportunities to shift out of fishing, for instance, even if it is not economically or ecologically viable (e.g. if you don’t have land, are in debt, and only have your fishing gear, it can be near impossible to find other options). If these kinds of larger policies facilitate cycles of debt/poverty and reduce options of what people can do for a living, I wonder how policies at the government or community level could help to support the social side of conservation instead, considering the ways it impacts different people in differently.

Conversations with Erik

Another part of the field trip that stood out to me was our conversations with Erik W. This part of the field trip was a highlight for me and I feel so much gratitude toward Erik for having taken the time to share his incredible reflections, knowledge, and experiences with us.

One big idea I learned from this is the very limited role that observers can play in monitoring Canadian fish stocks. Between the limited trawlers types they are on, the short hours they work, and the legal weight to the captain’s logbook over their own, the observer role seems more hypothetical than actual in terms of its potential impact and regulation. It was also interesting to hear a fisherman’s perspective on trawlers as Erik did not seem happy with their presence on this coast. Based on what I know of them, this solidified the idea that trawlers should be banned entirely.

Besides this annoyance with trawlers, there were a number of commonalities between Erik, a fisherman, and what I’ve been learning about ocean conservation. I was struck by how Erik thought that fisheries should be more tightly managed (not just “managed to death”). This similarity — that fishers and conservationists both want sustainable fish stocks — seems obvious in some ways, but I hadn’t concretely realized that commonality before. Based on our conversation with Erik, fishers want fair, sustainable regulations around fishing so that people can fish for years to come in a way that fairly benefits those involved.

Along these lines, our conversation around quotas, specifically individual and individual transferable ones is lingering with me as well. The non-individual quota, or in Erik’s words, “madhouse fishery,” does not seem good from a fishers’ or a conservationists’ perspective as it creates a dash to get as much fish as possible before your competitor does. This does not lead to best practices or prices, and can result in huge amounts of waste. However, when quotas are individual, it was interesting to learn how the transferable part could lead to larger, more wealthy people and businesses purchasing all these licenses, which does not seem like a good outcome for the smaller scale fishers and I imagine could lead to other issues too. I wonder what the best way to manage fish stocks is and if there are other methods that have better results.

Overall, this was a hugely impactful field trip and was one that I’m very thankful to have had the opportunity to be a part of!

Acknowledgements

There are so many people who helped shape my learning journey and facilitate our experiences in Steveston. I’m hugely grateful to Erik W., Kimberly, Rachel, Jane, and Andria for taking the time to share the Britannia Shipyards, Gulf of Georgia Cannery, Steveston docks, and their wealth of knowledge and experiences with us during our field trip. Thank you to Dr. Amanda Vincent and Tanvi Vaidyanathan for facilitating this incredible opportunity and our learning journey so far — it has been such a privilege to learn from you!

Beyond this gratitude, I would also like to acknowledge that I am a white settler and while unintended, the writing of this reflection will have been affected by my experiences and positionality. To the best of my knowledge, the writing of this reflection and the place where the field trip occurred took place on the unceded, ancestral, traditional, and current lands of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh peoples. While this reflection has mostly focused on settler-colonial histories, this is not with the intention of dismissing the incredible depth of stories and experiences or presence of these nations and peoples. I feel incredibly privileged and grateful for the opportunity to live and work in this place.

Thank you for reading!

Image Sources (listed in order of image appearance)

@linneamorgan_14. “Had the pleasure of getting a tour of @Steveston for #OceanConsvnUBC on Tuesday. Came out of that field trip having a much better understanding of the socioeconomic side of fisheries here in BC.” Twitter, 14 Mar. 2019, https://twitter.com/linneamorgan_14/status/1106243868989759493.

“Fishermen’s Reserve rounding up Japanese-Canadian fishing vessels on 10 Dec. 1941.” CBC/RadioCanada, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/lost-fleet-exhibit-shows-how-racist-policies-devastated-b-c-s-japanese-fishing-community-1.4041358.

Vincent, A. Ocean Conservation and Sustainability: Content, n.d., https://blogs.ubc.ca/biol420ocean/content/.

@AmandaVincent1. “Eric Wickham, commercial fisherman and author of Dead Fish and Fat Cats, gives my BIOL420 class a wonderful introduction to the realities of fishing. @Steveston. #OceanConsvnUBC @UBCoceans.” Twitter, 12 Mar. 2019, https://twitter.com/AmandaVincent1/status/1105605792105783296.

@AmandaVincent1. “So glad to be @Steveston with the outstanding students from my BIOL 420 class @UBC. Marine conservation comes alive in hearing from people who depend on the sea. #oceanConsvnUBC. @TanviVaidyanath.” Twitter, 12 Mar. 2019, https://twitter.com/AmandaVincent1/status/1105602085540655105.