Lera Boroditsky’s SAR lecture from May 2017 was fascinating and thought-provoking, prompting numerous connections to my own experiences and ideas. She begins (00:35) with a powerful image—language as a ‘magical’ ability unique to humans. This struck me immediately, especially as she explained how language allows us to plant ideas in one another’s minds. For me, this concept resonated deeply with my role as a teacher. The words I choose in the classroom are not just communication tools; they are seeds that can shape how students think and view the world. I reflected on my responsibility to use language thoughtfully, knowing that it can either nurture or limit a student’s ability to think critically and creatively. As I watched the rest of the presentation, I continued to make connections mostly with my teaching experience.

At the 11:18 mark, Boroditsky discusses how different languages organize time. She shares an example from the Aymara people of the Andes, who view the past as in front of them and the future as behind them. This perspective is grounded in the idea that the past is known and the future is unknown. I found this notion compelling. It made sense—yet, of course, I had never considered it, likely because my own language shapes my thinking. In English, we say ‘looking back’ when referring to the past and ‘looking forward’ when discussing the future. These expressions have shaped my perception of time to such an extent that I never imagined an alternative way of thinking about it.

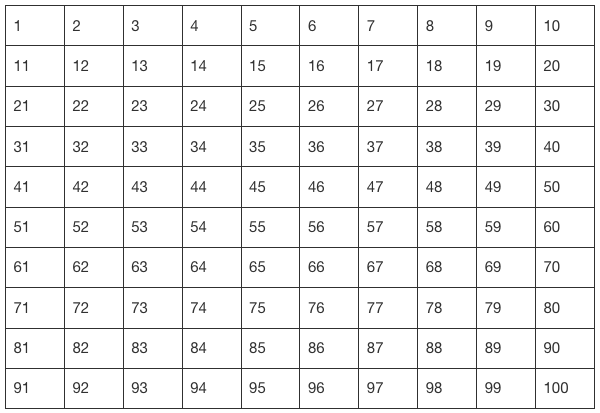

All the talk about how different languages organize time led me to reflect on a change I made in my classroom a few years ago—one that relates to how we perceive information and the language we use. The hundred chart is a common tool for developing early numeracy skills, particularly in grades K-2. In most classrooms, the chart looks like this (Figure 1), where students learn to see patterns, such as counting by 2s, 5s, and 10s, and to explore math concepts like ‘one more/one less’ and ‘ten more/ten less.’

Figure 1

A Typical Hundred Chart

However, there is a problem when students use directional language in relation to the chart. For example, if a student is asked to add 10 more while pointing to 46 on a typical hundred chart, they would move their finger down the chart to land on 56. While the number is increasing, the visual movement on the chart contradicts the language—’ up’ for increasing and ‘down’ for decreasing—which can create confusion. This ‘directional conflict’ can be especially problematic for students with disabilities (Randolph & Jeffres, 1974, p. 203, as cited in Bay-Williams & Gletcher, 2017). In response, I began using a bottom-up version of the hundred chart (Figure 2).

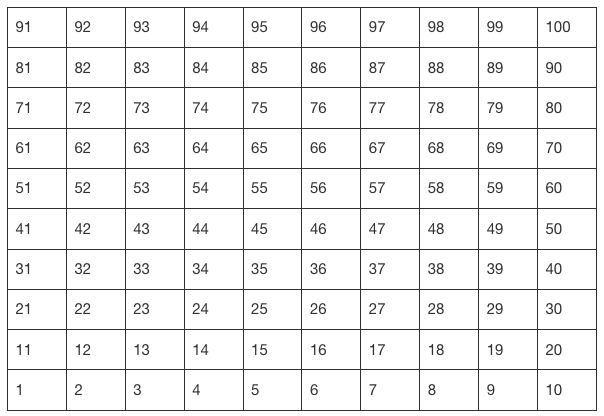

Figure 2

A Bottom-Up Hundred Chart

Now, when students talk about adding 10 more, they move their finger ‘up’ the chart, and the language matches the movement—’ going up’ corresponds with the number value increasing. Bay-Williams & Gletcher (2017) suggest that this alignment between language and visual representation helps students more easily grasp concepts of ‘more’ and ‘less.’ This change has made a noticeable difference in my classroom. By matching the directional language to the chart’s visual movement, students gain a better understanding of mathematical concepts. And while this solution works well for English speakers, it highlights how language plays a crucial role in shaping our cognitive processes. For example, in right-to-left languages, a different hundred chart orientation would be necessary to align with their directional language. This reinforces the idea that language influences not just communication but the way we think and understand the world around us.

Boroditsky says that “the kind of language that swims around you, the grammatical forms that swim around you and that are in your environment change what you attend to, even when you’re looking at new events, unrelated to what you’ve just been hearing about” (SAR, 2017, 33:52). In this example, Boroditsky is referring to test subjects identifying who committed an act, with their perceptions shaped by the grammatical structure of the language they had been exposed to prior to the experiment. However, this also resonated with me in terms of the power teachers wield. The words I choose, the order in which I say them, and even my tone may influence what my students focus on and how they interpret information. It’s mind-blowing to consider the extent of that impact.

At the 34:05 mark, the conversation shifts to the language of counting and numbers, which is something I have often thought about. In grade 2, the expectations for students jump drastically—from knowing numbers 1 to 20 to knowing numbers 1 to 100. This is a huge leap, and it has caused me to wonder how other languages handle counting. The only other language I am somewhat familiar with is French, and I have wondered if the French approach to numbers over 50 allows French students to have a better, worse, or the same number sense of numbers between 50 and 100. When counting in French, understanding the computation behind larger numbers is essential. For instance, the number seventy-two is translated as “soixante-douze” (sixty-twelve), making me wonder whether this method helps French speakers develop better number sense.

Additionally, in my experience teaching grade 1 students to count between 11 and 20, I’ve often felt that there should be a better system. Numbers 11 and 12 are especially tricky, 13-15 are slightly easier, but even 16-19 present challenges. What exactly is a “teen”? Why don’t we have a counting system that works more like “10-1, 10-2, 10-3” to help students build a clearer understanding of numbers 11-19? Schiltz et al. (2024) discuss this in terms of “the transparency of the number system of a particular language (e.g., in Russian’ ‘one-ten’ for ’11’ is transparent, while “eleven” in English is not)” (p. 2416). From my experience teaching grade 1 students, I have found that the English words for 11 to 19 make numerical thinking more challenging for young students. I suspect that Russian-speaking students, with their more transparent system, might develop number sense more easily.

At 42:47 in the recording, Boroditsky explains one method of researching for causality between language and thinking. This process involves training people to speak in new ways and then observing changes in their thinking. I find this idea fascinating, and it reminds me of the work I do with my students around growth mindset language. Instead of letting a child say, “I can’t do that,” I encourage them to say, “I am still working on learning how to do this,” or “I can’t do this yet.” To help emphasize the power of the word “yet,” I use the picture book The Magical Yet by Angela DiTerlizzi. This book introduces students to “a most amazing thought rearrange-er” (DiTerlizzi & Alvarez, 2020, p. 8)—the magical creature known as The Magical Yet. The story shows how language can change how we think, or as the book puts it, how it can act as a “thought rearranger-er.”

During the Q&A session, Boroditsky responds to a question from the audience about whether teaching literature can enhance brain development. The answer given by Boroditsky is that “there’s some suggestion that reading fiction improves your theory of mind, so theory of mind is this ability to read other people’s minds and infer their intentions and think about what it is they might be thinking” (SAR, 2017, 53:32). This was an intriguing concept for me to hear. As an elementary teacher, I practice this every day. I read to my students, and we discuss the characters’ emotions and motivations. Although research on this is still in its early stages, hearing Boroditsky’s statement reinforced just how powerful literature can be.

Although not in chronological order, I have saved what I think is the most powerful statement of the talk for the end. At the 18:38 mark, Boroditsky states, “Language has this causal power. You can change how people think by changing how they talk” (SAR, 2017). This is the key takeaway, and as an elementary educator, I find it extremely profound and encouraging.

References:

Bay-Williams, J. M., & Fletcher, G. (2017). A bottom-up hundred chart? Teaching Children Mathematics, 24(3), e1-e7. https://doi.org/10.5951/teacchilmath.24.3.00e1

Boroditsky, L. (2011). How language shapes thought. Scientific American, 304(2), 62-65.

DiTerlizzi, A., & Alvarez, L. (2020). The magical yet (First ed.). Disney-Hyperion.

SAR School for Advanced Research. (2017, June 7). Lera Boroditsky, how the languages we speak shape the ways we think [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iGuuHwbuQOg

Schiltz, C., Lachelin, R., Hilger, V., & Marinova, M. (2024). Thinking about numbers in different tongues: An overview of the influences of multilingualism on numerical and mathematical competencies. Psychological Research, 88(8), 2416-2431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-024-01997-y

Hi Natalie, I really enjoyed reading your reflections on Boroditsky’s lecture and how they connect to your teaching, particularly the numeracy component. Your example of the hundred chart and how directional language affects perception is quite interesting, and the way you redesigned the chart makes me reconsider the normative aspects of the diagrams and images we use in the classroom. For instance, as a Socials teacher, it reminded me of how we use timelines and phrases like “looking back” or “looking forward,” which subtly shapes how we think about time and history. Other cultures view history as cyclical rather than linear, and so might use completely different language or imagery. Have you come across any other classroom tools or practices where language might be unintentionally reinforcing a particular worldview?

Thanks for your feedback. To clarify, I didn’t redesigned the chart, I revamped the one I use in my classroom after reading an article by Bay-Williams and Fletcher (2017). I am going to keep thinking on your question but welcome all other member of the course to also comment on this as well.

References:

Bay-Williams, J. M., & Fletcher, G. (2017). A bottom-up hundred chart? Teaching Children Mathematics, 24(3), e1-e7. https://doi.org/10.5951/teacchilmath.24.3.00e1