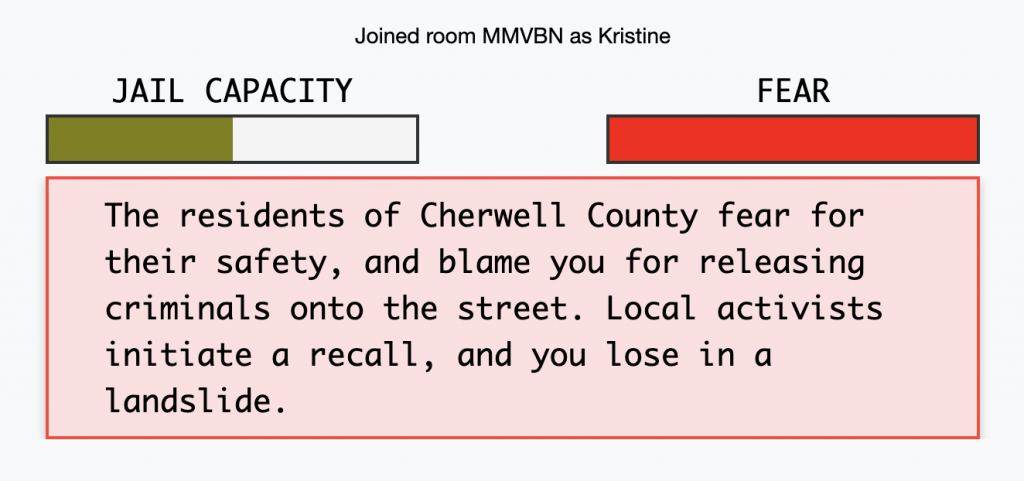

The Detain/Release is an AI (Artificial Intelligence) simulation game that works as an algorithmic risk assessment tool. I found this task difficult to complete in part because even though it is a simulator, there was still a feeling of “stress” involved in the decision-making process. Each time I made a verdict, I wondered what the ramifications might be for the defendant and/or the general public, or for those in direct relationship with the defendant (i.e. family, children). At every trial, I was torn. For each final decision I made, I wondered if it might result in a bigger consequence such as homicide, rape, loss of a home or job, or even death by suicide. Being given limited information on each defendant made the scenario even more difficult. I wondered what the program was learning from each of my decisions. What was it determining? Was it choosing specific people based on my previous decisions? The program also has you considering whether the defendant will re-offend if released from custody. It also wants you to consider public opinion, demonstrated by local newspaper articles and the fear level of the general public.

Reflecting on the simulation process, I can’t imagine using a risk assessment tool in isolation for decision-making in the judicial system, as it pertains to this task. Considering that algorithms are created using mathematics, it is limited. Algorithms fail to have human thought, compassion, and nuance.

One of the creators of Detain/Release notes that, “the mere presence of a risk assessment tool can reframe a judge’s decision-making process and induce new biases, regardless of the tool’s quality” (Porcaro, 2019). Because the simulation uses machine learning, there is potential for biases from the data and algorithm used to make predictions. This simulation brings up an important point of noting that AI biases, although not necessarily intentional, do exist. Human biases inform algorithmic development. Since computer data is processed using identified patterns, the data continues to grow based on these patterns.

Biases are evident with respect to real-life applications with AI. The article “Justice in the Age of Big Data” provides an example of the predictive crime model called PredPol system. PredPol uses data that targets crime in geographical locations. When the program is setup, police have the choice on how to setup the program. The program can include data on Part 1 crimes (violence, homicide, arson, assault) and/or Part 2 crimes (vagrancy, aggression, panhandling, selling/consuming small quantities of drugs). Typically, Part 2 crimes would not be recorded. “These kinds of crimes are endemic to many impoverished neighborhoods” (O’Neil, 2017). Patrolling police officers visit these areas more frequently based on the amount of data. “These low-level crimes populate their models with more and more dots, and the models send the cops back to the same neighborhood” (O’Neil, 2017). This in turn, justifies more policing. Prisons fill up with more people who are convicted of victimless crimes, mainly black and brown people. “PredPol, even with the best of intentions, empowers police departments to zero in on the poor…and they have cutting-edge technology (powered by Big Data) reinforcing their position”. The aspect of fairness when determining a verdict in the judicial system is also difficult to quantify because it is a concept because programs “tend to favor efficiency” over fairness. The author points to programs like PredPol as being weapons of math destruction (WMD) “that encode human prejudice, misunderstanding and bias into their systems”. Equality also plays a key role. “The biased data from uneven policing funnels right into this model. Judges then look to this supposedly scientific analysis, crystallized into a single risk score. And those who take this score seriously have reason to give longer sentences to prisoners who appear to pose a higher risk of committing other crimes” (O’Neil, 2017).

An article in Fordham Law Review suggests when using AI for decision-making processes, the implications are important to understand and have real consequences. The author (Liu, 2019) notes the following concerns:

- Bias and discrimination – the inherit biases of the creators or the data sets are trained, which can result in discriminatory outcomes for certain groups/people

- Lack of transparency – difficult to understand how a decision was made based on the complexities of AI algorithms, making it difficult to identify and correct errors

- Ethical concerns – relying solely on AI can raise concerns about morality. There is a risk that the use of AI could normalize and exacerbate human rights abuses

- Systematic change – relying on AI for decision-making in the criminal justice systems could lead to shifts away from human judgment and discretion.

In the article “How Can We Stop Algorithms Telling Lies”, the author suggests that, “When we find problems we need to enforce our laws with sufficiently hefty fines that companies don’t find it profitable to cheat in the first place. This is the time to start demanding that the machines work for us, and not the other way around” (O’Neil, 2017).

Gary Marcus, is an author and cognitive scientist who is known for his extensive research in AI and machine learning. In a 2017 article, Marcus stated that, “there’s a huge bias in machine learning that everything is learned and nothing is innate, which ignores human instincts and brain biology. In order for machines to form goals, determining outcomes, and problem-solve, algorithms need to emulate human learning processes much more accurately. And that will take some time” (Marcus, 2017).

References:

Liu, J. (2019). The limitations of using artificial intelligence in decision-making in the criminal justice system. Fordham Law Review, 88(2), 617-654.

Marcus, G. (December 6, 2017). Gary Marcus probes AI’s limitations. MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy. Retrieved from https://ide.mit.edu/insights/gary-marcus-probes-ais-limitations/

O’Neil, C. (April 6, 2017). Retrieved from Justice in the age of big dataLinks to an external site. TED. Retrieved August 12, 2022

O’Neil, C. (July 16, 2017). Retrieved from How can we stop algorithms telling lies?Links to an external site. The Observer

Porcaro, K. (2019). Detain/Release [web simulation]. Berkman Klein Center.

Porcaro, K. (January 8, 2019). Detain/Release: simulating algorithmic risk assessments at pretrial.Links to an external site. Medium.

Sarah Ng

March 25, 2023 — 12:49 pm

Hi Kristine,

Although this assignment focuses on detaining or retaining criminals, I couldn’t help but think about how AI affects regular people. It wasn’t until about three years ago that I learned companies use AI to filter through job applications. I quickly knew that I had to rethink and redo my job application documents because AI concluded that I wasn’t an appropriate applicant for the jobs I was applying for. Just like when we were playing the simulation game of determining someone else’s fate, AI already decided the applicants’ fate before reaching the recruiters. It looks like AI is here to stay, what needs to be done to ensure all applicants are being provided with an equal chance of applying for a job?