Hello!!

As my final post, I really wanted to focus on a wrap-up of everything we have learned, especially in regards to outside influence in Latin America. As we have seen through this week’s documents as well as Jon’s discussion on corruption and how it opens up possibilities, Latin America is still often considered by westerners as ‘blank slate’ where anything can take place and the rule of law of another country must be implemented in order to get people to listen to injustices, like it happened with the Texaco case.

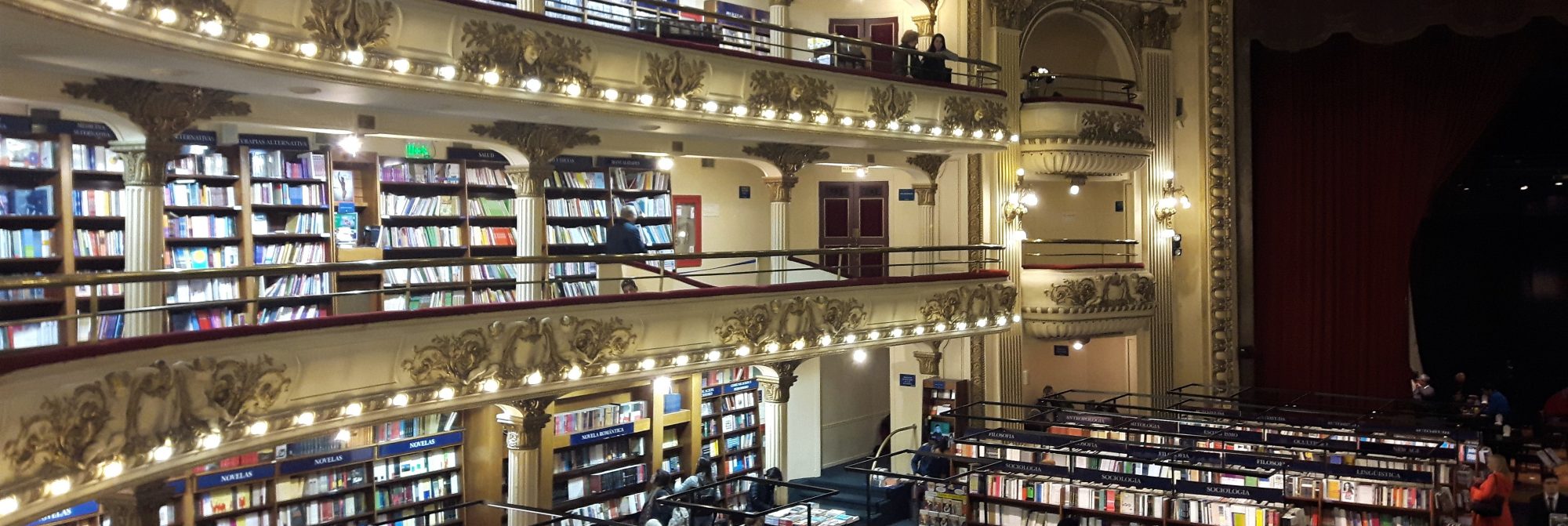

The legacy of corruption, misuse of the environment, wars, and other largely negative experiences have plagued Latin America for centuries and it will certainly continue to take place, as one cannot escape their past. However, it is so worth remembering that the ‘Kodak’ images of ‘happiness’ often portray individuals or groups in Latin America living their lives or celebrating calendar events. I mention this because more than anyone else, in my opinion, Latin Americans are resilient and will never stop fighting for what they believe is right. It is narrowing down the focus of ‘what is right’ within each country that has to be worked on, since the area’s past has created such division, but in a large part from what I have lived and what we have studied, Latin Americans are fighters and do not stop living because the conditions they are in are less than ideal.

I think there is a lot we can learn from Latin American’s past and present. We live in a country that presents itself as a haven for immigrants and refugees, but have so much to work on. Canada covers its dark past and ignores it in a large part, rather than engaging with it head on like Latin Americans have had to do in many instances. There is much we can learn from Latin America and it’s time we listen…