I really liked the Campbell reading, especially how it broke down the murals in terms of their historic significance and their implicit symbolism. The following are some of my thoughts I wrote down as I was reading the passage.

On pages 30-31, Campbell quotes Arnold Belkin lamenting the “fall” of Mexican muralism, saying, “If mural painting is being developed with increasing vigor in other countries, how can we allow it to die here? Earlier in this century Mexican muralism was an inspiration for the rest of he world. Now it is up to us to restore that inspiration.” This idea of creating or restoring inspiration struck me as funny, since inspiration usually seems to me to be something organic and highly individualised. Fabricating or forcing inspiration misses the point.

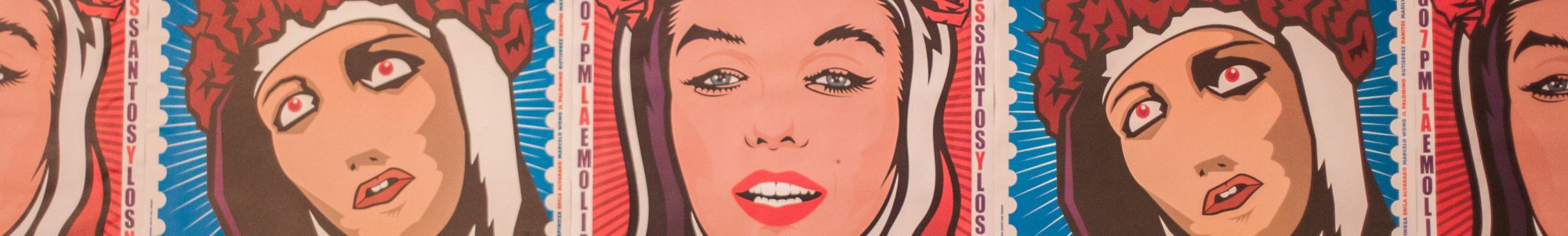

I was intrigued by the conflict between Hijar and Ehrenberg over the question of whether H20’s murals were “Mexican muralism”. Hijar argued that Ehrenberg’s murals took a scientific direction, deviating from the Mexican muralism’s “two basic tendencies” of “institutional muralism and an oppositional muralism integrated to communities of struggle” (p. 32-33) and thus undermining the art form. Ehrenberg responded by embracing this notion of deviation. To me, the entire argument seems arbitrary, since it seems to me that murals painted in Mexico by Mexicans should logically be considered “Mexican muralism” regardless of whether they follow the Mexican school or not; getting caught up in the technicalities of defining art takes away from the art itself.

On p. 35 Campbell writes that the text on Diego Rivera “is enjoined mythically by the editors of the collection through a suppression of standard historical points of reference such as a bibliographical data or contextual information for the selected texts. Hence the anthology positions Rivera and his muralism within the same timeless national cultural space as the archaeological digs and pre-Colombian pyramids on the tourist maps.” This idea of authors working collectively to create build up an artist who transcends a time stamp is kind of cool but also makes you consider the influence of historical framing in the process of popularizing or highlighting certain aspects of culture.

The quote “there is a salient contradiction between the mural image as monument of an official national identity and that of tendentious re-motivations of national cultural patrimony,” (p.36) resonated a lot with me. While I agree that there is this inherent contradiction in the government using a symbol of uprising as a unifying national image, the fact that there is conflict embedded in the national symbol of a nation ravaged by conflict is kind of perfect. Furthermore, the fact that both the people and the government created and defaced one anothers’ murals adds to the perfection in my mind.

Lastly, Vasconcelos’ image of a post-racial society sounds less racist and more aesthetically pleasing the way it is framed in this reading. When you remove yourself from the details of his writing, it does seem creative to combine the encouragement of the arts and nationalism into one project. This is not to say, however, that I don’t still take issue with what he wrote in his paper.

Ran out of words/time for Taussig. Looking forward to class discussion.