Reading this text was very interesting. Firstly because football is the national sport in my country and growing up, football games were all around me, embedded in the Italian culture. It has been a while I have not seen any match and this article brought me back to the good old times.

Secondly: I did not know anything about the Brazilian Maracaña match of 1950! I knew Brazil was very attached to football as a nation, but this explains so much more.

It struck me how important the 1950 defeat has been for Brazilians. It sounded almost as an obsession. I can’t believe so many different literacies have been written about it. I didn’t finish reading the text so this is all I can say. All in all it was very pleasing to read as well as informing. It makes me think how sports are nowadays related to specific cultures all around the world. Almost every nation has a national sport, (I guess?), and it is so interesting to see how much they make up people’s identities as part of a country, a culture, a nation.

Monthly Archives: March 2017

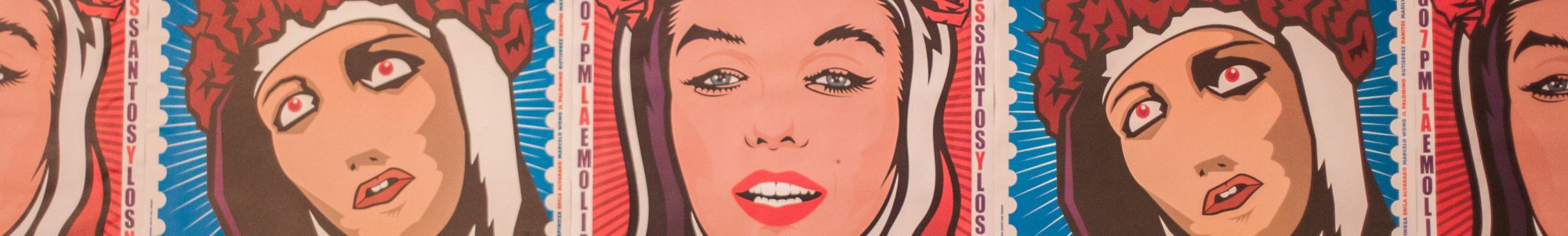

Reality and its Mirrors

I love melodramatic trash TV (not necessarily saying telenovelas are trash, they sound like quite the opposite but don’t worry i will get to that ) and not in some ironic way (still seriously don’t get how it’s possible to like something genuinely and ironically?) I truly truly love it (the good trash that is.) I think everybody does to some degree (this may be my bitterness speaking but I feel as though “male” targeted trash programming is less villified/condemned than it’s “female” targeted counterparts…looking at you “history channel” you are in no way superior to Kardashianess ) there are elements of melodrama in almost all modern modes of communication from what we read in magazines, see on the news or even project with our internet “selves.” I moved to the U.S. when I was 8 and went from a tiny town with one elementary school of like 50 children straight into a giant “middle school” and more importantly into the world of television, which I only ever saw movies/cartoons/news on before (cus my cheepo parents refused to pay for things like cable and air-conditioning and still do.) My older sister and I both became obsessed with our tv because a) we had no friends after moving b) there was so much yet to be discovered on that thing c) it was all so over the top and ridiculous and exciting. Also we had our own “play room” in the basement where we could vegetate in front of our disturbing programming undisturbed by our parents and quickly hit the “last channel” button whenever we heard their footsteps down the stairs. So with one small change in circumstance my sister and i went from arguing over which one of us was D.W. and which one was Arthur to contemplating “A Shot at Love with Tila Tequila” (a google search will tell you what you need to know, the shame still haunts me.) Also we would watch reruns of american sitcoms that we didn’t even know existed before moving because most were canceled before we were born like “full house” “sister, sister” “family matters” “7th Heaven” etc, all equally awful and cheesy but it was on this very rerun channel where I first encountered soap operas and on occasion, telenovelas (which, upon reflection were probably but not certainly Mexican.)

There is something so distinct about the set/lighting/costumes/general aesthetic of these programs which makes them easily recognizable as their genre. Maybe it has to do with the powder-coloured extravagant interiors with lace curtains, high ceilings and candelabras- the obvious artificiality which provides a perfect backdrop for the very realistic elevated emotional rollercoaster which is the dialogue. Also this may be inappropriate and a mere matter of preference but I have always found the female protagonists of telenovelas to be more beautiful/better actors than in English soap operas, or at the very least better at delivering a convincing portrayal of dialogue (that i don’t even understand) and vivid emotion. Though I can’t say I ever stuck around long enough to consume a full telenovela (or that I ever knew what was going on) they are certainly visually superior to American/British soap operas. Also, interesting to note the difference between the content of “soaps” in individualist, money hungry societies, such as ours tend to focus more on business, scandal, prestige, and opulence i.e. issues of REPUTATION where the Latin American versions seem more concerned with familial dynamics and private as opposed to public forms of betrayal i.e. issues of COMMUNITY. The genre itself seems to be refined to perfection by its Latin American incarnation. They are proliferated through time by their ability to represent different kinds of people and “bridge the gap” of opera and drama portraying only the upper classes this “insists on the importance of the ordinary” – melordrama. The english name of the genre would imply this is it’s entire aim- Opera being a form of “high culture” with many conventions going along with the title, soap implying that it is being brought down to the common level (and also referencing it’s female audience) and should be consumed by everyone. Both high and low- another example of “mixture” at work! I was also really intrigued by the tropes we think of like inter-family drama and extra marital affairs being placed alongside traditional myths, stories and songs- wow, much mixture, very cool! Issues of representation are important, and the bad behaviour of only rich and untouchable people being glamourized can get stale after too long, I think people really are interested in confronting depictions (however dramatic) of issues that are real to them as well as a variety of characters which may represent them or be relatable to them. The dependency of the structure of the program on the structure of it’s society (seen in the different carnations of telenovela for different countries) as well as the many genres inside the genre (Political, ecological etc) prove how far reaching this genre is within Latin America, and just how successful it is in reflecting an artificial yet tangible mirror of reality for people to relate to and possibly learn from. Also, it’s worth noting how American reality and sitcom tv could take a nod from telenovelas, i need better, more realistic trash to consume!

Reality and its Mirrors

I love melodramatic trash TV (not necessarily saying telenovelas are trash, they sound like quite the opposite but don’t worry i will get to that ) and not in some ironic way (still seriously don’t get how it’s possible to like something genuinely and ironically?) I truly truly love it (the good trash that is.) I think everybody does to some degree (this may be my bitterness speaking but I feel as though “male” targeted trash programming is less villified/condemned than it’s “female” targeted counterparts…looking at you “history channel” you are in no way superior to Kardashianess ) there are elements of melodrama in almost all modern modes of communication from what we read in magazines, see on the news or even project with our internet “selves.” I moved to the U.S. when I was 8 and went from a tiny town with one elementary school of like 50 children straight into a giant “middle school” and more importantly into the world of television, which I only ever saw movies/cartoons/news on before (cus my cheepo parents refused to pay for things like cable and air-conditioning and still do.) My older sister and I both became obsessed with our tv because a) we had no friends after moving b) there was so much yet to be discovered on that thing c) it was all so over the top and ridiculous and exciting. Also we had our own “play room” in the basement where we could vegetate in front of our disturbing programming undisturbed by our parents and quickly hit the “last channel” button whenever we heard their footsteps down the stairs. So with one small change in circumstance my sister and i went from arguing over which one of us was D.W. and which one was Arthur to contemplating “A Shot at Love with Tila Tequila” (a google search will tell you what you need to know, the shame still haunts me.) Also we would watch reruns of american sitcoms that we didn’t even know existed before moving because most were canceled before we were born like “full house” “sister, sister” “family matters” “7th Heaven” etc, all equally awful and cheesy but it was on this very rerun channel where I first encountered soap operas and on occasion, telenovelas (which, upon reflection were probably but not certainly Mexican.)

There is something so distinct about the set/lighting/costumes/general aesthetic of these programs which makes them easily recognizable as their genre. Maybe it has to do with the powder-coloured extravagant interiors with lace curtains, high ceilings and candelabras- the obvious artificiality which provides a perfect backdrop for the very realistic elevated emotional rollercoaster which is the dialogue. Also this may be inappropriate and a mere matter of preference but I have always found the female protagonists of telenovelas to be more beautiful/better actors than in English soap operas, or at the very least better at delivering a convincing portrayal of dialogue (that i don’t even understand) and vivid emotion. Though I can’t say I ever stuck around long enough to consume a full telenovela (or that I ever knew what was going on) they are certainly visually superior to American/British soap operas. Also, interesting to note the difference between the content of “soaps” in individualist, money hungry societies, such as ours tend to focus more on business, scandal, prestige, and opulence i.e. issues of REPUTATION where the Latin American versions seem more concerned with familial dynamics and private as opposed to public forms of betrayal i.e. issues of COMMUNITY. The genre itself seems to be refined to perfection by its Latin American incarnation. They are proliferated through time by their ability to represent different kinds of people and “bridge the gap” of opera and drama portraying only the upper classes this “insists on the importance of the ordinary” – melordrama. The english name of the genre would imply this is it’s entire aim- Opera being a form of “high culture” with many conventions going along with the title, soap implying that it is being brought down to the common level (and also referencing it’s female audience) and should be consumed by everyone. Both high and low- another example of “mixture” at work! I was also really intrigued by the tropes we think of like inter-family drama and extra marital affairs being placed alongside traditional myths, stories and songs- wow, much mixture, very cool! Issues of representation are important, and the bad behaviour of only rich and untouchable people being glamourized can get stale after too long, I think people really are interested in confronting depictions (however dramatic) of issues that are real to them as well as a variety of characters which may represent them or be relatable to them. The dependency of the structure of the program on the structure of it’s society (seen in the different carnations of telenovela for different countries) as well as the many genres inside the genre (Political, ecological etc) prove how far reaching this genre is within Latin America, and just how successful it is in reflecting an artificial yet tangible mirror of reality for people to relate to and possibly learn from. Also, it’s worth noting how American reality and sitcom tv could take a nod from telenovelas, i need better, more realistic trash to consume!

Mass Culture

Big Snakes on the Streets and Never Ending Stories: The Case of Venezuelan Telenovela

Ortega begins the passage my asserting that “the telenovela is an important expression of Latin American popular culture not only because of its success with public, but also because it reflects this public’s symbolic and affective world.” In Venezuela the genre is divided into two phases, the “proto-novela” (1953-1972) and the contemporary telenovela(1973-1992). These genres break down further into the “cultural novela” and the “urban novela.” The author positions the telenovela in context to the North American soap opera claiming that both “coincide, in a general way, in thematic treatment of family, power relations, the bad woman… etc.” The distinction therein is that, “the central motivations of the soap opera are money and sex, whereas the motivation for the telenovela, according to Jose Antonio Guevara, is the continuation of a family: to fall in love, to marry, to have children.” The telenovela works to contrast extremes (rich, poor, good, and evil) to yield melodrama. The author later sites Peter Brooks regarding melodrama, claiming that, “[it] is a popular form not only because it is favoured by the audience, but also because it insists– or tries to insist– in the dignity and importance of the ordinary.” Ortega believes that, melodrama included, the purpose of the telenovela is to illuminate problems within “contemporary society” directly opposing soap opera’s entertainment purposes. Telenovelas also depart from soap operas in their diverse audiences and evening broadcasting times

Structurally speaking, the telenovela has the classic beginning, middle, and end that characterize fully-resolved stories, unlike soap operas. Making reference to William Rowe and Vivian Schelling, the author cites these two saying, that the telenovelas origins “can be traced through a series of popular forms, beginning with folletin, or newspaper serial, itself transitional in that it was a first step whereby traditional oral themes and styles entered the medium of print at the same time as their audience negotiated literacy”. The most important influence, according to the author, was the radio soap opera. Ultimately this passage worked to emphasize the role of telenovelas as “technological apparatus to recreate the country as fiction.”

Popular Culture as Mass Culture

This week I decided not to summarise the readings as much, but instead write down my personal reactions to the pieces as a whole:

For both pieces, it was incredible to see the depths at which popular culture can be embedded within a society. In the case of Latin America, it is embedded in ways that are not detached and languid as seen more commonly within other societies. Instead it is integrated in through greatly personal and emotional attachments to the pop culture (ie. sport/telenovela). Yes, these passionate attachments to a ‘pop-culture’ are also seen within Western and other societies (most commonly in sport, politics, religion music and art) however, these attachments are not as all encompassing in terms of the mass population. Latin American culture continues to merge and explore the polarities of their people and unite them in a love and passion for something (an aspect of pop-culture), making that ‘something’ core to everyday life and to what it means to be from that country.

These readings fascinated me as the lines between the experience of the mass and the experience of the individual are very shared. On their own accord people are passionate about something and that is shared in the masses making them insanely powerful. The power of the people is seen in the political unease created by the telenovela and the mourning of Brazil’s 1950 world cup loss. It was interesting to see how emotion, passion and simply loving something A LOT, dictate to some extent the political actions, decisions and social order.

Futbol and Telenovelas

I really, really enjoyed the reading Futbol this week! I felt that’s what I had in mind I would learn about when I signed up for this course, so it felt good we finally were ready to learn about football and telenovela culture.

I had read and heard numerous time that football is akin to “religion” in Brazil, but I feel I had still underestimated how magnanimously important the sport is for Brazilians. Brazilians compare the loss at the 1950 World Cup (the Maracanazo) to the bombing of Hiroshima. The event is touted as the single worst national tragedy in Brazil’s sovereign history. The reason Brazilians were and still are so deeply affected by the loss is not only because of the passion they have for football, but also because a loss was projected by the media as unthinkable, the impossible. Newspapers, politicians, and radios had already hailed the Brazilian players the new world champions. Additionally, there were no televisions, therefore, most of the Brazilians had paid to watch the team play live, and thus watched the heartbreaking goal scored by Gigghia right in front of their eyes too. It was an image that never faded away from their memories. What made the loss worse was that rather than brushing off the defeat as a freak result, the Brazilians accepted it as something they “deserved”, that the “Brazilians were a naturally defeated people”. The loss reinforced a sense of inferiority and shame.

But putting aside the heartbreak of the general populace, the three players to suffered the most in the event’s aftermath were Barbosa (the goalkeeper), Bigode and Juvenal, coincidentally, all of them black. Therefore, the event reignited theories that “Brazil’s racial mixture was the cause of a national lack of character”. I really empathized with these three players while reading the text. The entire blame for the defeat fell on Barbosa, who was never allowed to forget 1950. He was labeled as “the man that made all of Brazil cry”. I cannot fathom how difficult and heartbreaking it must’ve felt to be made to feel the cause for millions of heartbreaks. Despite being voted as the best goalkeeper during the 1950 World Cup, he was shunned by his colleagues and called bad luck. Zizinho, another member of the 1950 Brazilian squad, described how adversely the event affected Barbosa, Bigode, and Juvenal. Bigode didn’t leave his house and Juvenal left Rio for good. It’s even sadder to realize that much of the reason why the blame fell completely on their shoulders was because of their skin colour, and not so much their football. It’s also interesting how, even though Zizinho says he moved past the event, he still has drawings of football systems lying around in his house. None of the players, even half a century later, were ever able to really put the fateful match behind.

Also, it was really interesting to find that Aldyr, the man who designed Brazil’s characteristic yellow football uniform after the 1950 World Cup, actually supports Uruguay, the team that caused the need for his design in the first place. Not only this, but Aldyr doesn’t particularly take much pride in his creation. I mean, sure he grew up on the Brazil/Uruguay border, and that explains his love for Uruguay, however, he literally is the designer of the most recognizable and famous jersey in sports!! Forget gloating, he doesn’t even take any pride in it?!

Finally, it was interesting to read what Gigghia, the guy who scored that fateful goal, had to say about the event. He is the poorest of all the surviving 1950 veterans, quite an irony. As much as I right now sympathize with the Brazilians, he deserved better treatment from the Uruguay government. He doesn’t feel much guilt for scoring the goal, but that’s hard to believe. That single goal he scored thrashed millions’ of people’s hopes, morales and self-esteems. He literally is the cause of Brazil’s Hiroshima. The worst part though is that the team that won that day, Uruguay, no longer remembers the much about the event, “In Uruguay, [they] lived the moment. Now it’s over.” But 5 years later, in Brazil, they “feel it in their hearts every day”. Actually, in hindsight, it was overall a very fun sad read and Barbosa deserved more love. I think I got too into it …

It was also very interesting to read about the Telenovelas produced in Latin America. Telenovelas are different from American soap operas in that while soap operas are driven by money and sex, telenovelas revolve around more family-oriented concepts, i.e. falling in ove, marrying and having children. It reveals a lot about the culture of Latin America, and what they value the most in life. Unlike soap operas, telenovelas also have a beginning, a development and an end, “because its goal is to “solve” life and provide it with a happy ending”. Ortega discusses Venezuela’s “Por estas calles” at length as an example of a modern telenovela and its theme, structure and characters and genres. The show was so interwoven with the national/political events in Venezuela, that it never enjoyed the same success in other countries that imported it. It was “too foreign” for them, highlighting how telenovelas are usually centred around contemporary political, affective and social issues.

Futbol and Telenovelas

I really, really enjoyed the reading Futbol this week! I felt that’s what I had in mind I would learn about when I signed up for this course, so it felt good we finally were ready to learn about football and telenovela culture.

I had read and heard numerous time that football is akin to “religion” in Brazil, but I feel I had still underestimated how magnanimously important the sport is for Brazilians. Brazilians compare the loss at the 1950 World Cup (the Maracanazo) to the bombing of Hiroshima. The event is touted as the single worst national tragedy in Brazil’s sovereign history. The reason Brazilians were and still are so deeply affected by the loss is not only because of the passion they have for football, but also because a loss was projected by the media as unthinkable, the impossible. Newspapers, politicians, and radios had already hailed the Brazilian players the new world champions. Additionally, there were no televisions, therefore, most of the Brazilians had paid to watch the team play live, and thus watched the heartbreaking goal scored by Gigghia right in front of their eyes too. It was an image that never faded away from their memories. What made the loss worse was that rather than brushing off the defeat as a freak result, the Brazilians accepted it as something they “deserved”, that the “Brazilians were a naturally defeated people”. The loss reinforced a sense of inferiority and shame.

But putting aside the heartbreak of the general populace, the three players to suffered the most in the event’s aftermath were Barbosa (the goalkeeper), Bigode and Juvenal, coincidentally, all of them black. Therefore, the event reignited theories that “Brazil’s racial mixture was the cause of a national lack of character”. I really empathized with these three players while reading the text. The entire blame for the defeat fell on Barbosa, who was never allowed to forget 1950. He was labeled as “the man that made all of Brazil cry”. I cannot fathom how difficult and heartbreaking it must’ve felt to be made to feel the cause for millions of heartbreaks. Despite being voted as the best goalkeeper during the 1950 World Cup, he was shunned by his colleagues and called bad luck. Zizinho, another member of the 1950 Brazilian squad, described how adversely the event affected Barbosa, Bigode, and Juvenal. Bigode didn’t leave his house and Juvenal left Rio for good. It’s even sadder to realize that much of the reason why the blame fell completely on their shoulders was because of their skin colour, and not so much their football. It’s also interesting how, even though Zizinho says he moved past the event, he still has drawings of football systems lying around in his house. None of the players, even half a century later, were ever able to really put the fateful match behind.

Also, it was really interesting to find that Aldyr, the man who designed Brazil’s characteristic yellow football uniform after the 1950 World Cup, actually supports Uruguay, the team that caused the need for his design in the first place. Not only this, but Aldyr doesn’t particularly take much pride in his creation. I mean, sure he grew up on the Brazil/Uruguay border, and that explains his love for Uruguay, however, he literally is the designer of the most recognizable and famous jersey in sports!! Forget gloating, he doesn’t even take any pride in it?!

Finally, it was interesting to read what Gigghia, the guy who scored that fateful goal, had to say about the event. He is the poorest of all the surviving 1950 veterans, quite an irony. As much as I right now sympathize with the Brazilians, he deserved better treatment from the Uruguay government. He doesn’t feel much guilt for scoring the goal, but that’s hard to believe. That single goal he scored thrashed millions’ of people’s hopes, morales and self-esteems. He literally is the cause of Brazil’s Hiroshima. The worst part though is that the team that won that day, Uruguay, no longer remembers the much about the event, “In Uruguay, [they] lived the moment. Now it’s over.” But 5 years later, in Brazil, they “feel it in their hearts every day”. Actually, in hindsight, it was overall a very fun sad read and Barbosa deserved more love. I think I got too into it …

It was also very interesting to read about the Telenovelas produced in Latin America. Telenovelas are different from American soap operas in that while soap operas are driven by money and sex, telenovelas revolve around more family-oriented concepts, i.e. falling in ove, marrying and having children. It reveals a lot about the culture of Latin America, and what they value the most in life. Unlike soap operas, telenovelas also have a beginning, a development and an end, “because its goal is to “solve” life and provide it with a happy ending”. Ortega discusses Venezuela’s “Por estas calles” at length as an example of a modern telenovela and its theme, structure and characters and genres. The show was so interwoven with the national/political events in Venezuela, that it never enjoyed the same success in other countries that imported it. It was “too foreign” for them, highlighting how telenovelas are usually centred around contemporary political, affective and social issues.

Mass Culture

Marta Colomina describes the significance of the telenovella (and, I suspect, the reason we are reading this article as part of our class) that lies in its dialogue between the commercial language and the language of popular culture.

– The way the article describes it, the telenovella seems the perfect fusion of the terms we have used to describe the popular, ‘commercially produced and popularly received.’ Not only is it at the forefront of commercial culture, but it is sanctioned by the people whose lives it portrays.

– The way the telenovella acts almost as an account of Venezuela’s history, offering live commentary on events as they transpire. Specifically, the article mentions the exposure of ‘Great Venezuela’ for what it is, the ‘Poor Venezuela,’ and how the telenovella was a method of popular resistance to the propagandized image the government portrayed.

– Even the telenovella offers a take on hybridity. The article describes it as the method through which complex characters relate to ones that are simply good or evil. Hybridity in the case of the telenovella is not racialized, however, as Mark Millington would claim.

– The telenovella also portrayed governmental figures in ways accessible by the common people. By bringing them down to a ‘popular’ level, the telenovella resisted the sacrilized image of government officials ‘Great Venezuela’ sought to portray.

– The telenovellas also carry with them a sense of ‘orality,’ with characters offering exposition central to the plot of the ‘great snake.’ Here we do not see a conflict between a historically oral folkloric culture and a colonial written culture that insures immortality, but rather a synthesis of art and merchandise into the paradoxical telenovella, which reflects on life in Latin America as it is, not as it was.

– The telenovella is also a response to modernity. By focusing on the traditional values of continuing the family and homebuilding rather than the soap operatic (undeniably modern) values of sex and money the telenovella offers an entry point for pre-modernismo values into the modern popular. The medium of the telenovella is tied right into modernismo, and yet it reflects timeless values. In creating something modern, it does not seek to repress the past.

Alex Bellos’ article on the national importance of Futbol in Brazil was one of the easier readings we’ve had this year. I got the impression that Bellos is a football fan writing for football fans – he deeply indulges in the details of the game throughout his writing – yet I was able to get a lot from the reading fairly easily. One thing that stood out to me from the reading was how Futbol in Brazil dictated the popular as much as the popular supported Futbol. Bellos spends a good deal of his article describing the fallout of the 1950 World Cup and how it has come to be as definitive a divide of early and late 20th century as the World Wars were for Europe, supporting the argument that Futbol is as much an indicator of the popular in Brazil as anything.

On the contrary, it seems that other countries rely less heavily on the sport for national identity. Uruguay, as Bellos writes, hardly remembers the 1950 Cup.