The biggest thing I came away with from this week’s readings is the intense melodrama surrounding Latin American mass culture.

When I read the quote on the very first page of Ortega’s piece about the game of 1950 being “Our (Brazil’s) catastrophe, our Hiroshima” (43), I was put off. When the United States bombed Hiroshima in 1945, upward of one hundred and fifty thousand people died within the first year and many Japanese civilians who survived continued to suffer the effects of intense radiation exposure for years afterward. I’m sure the quote did not explicitly intend to downplay the gravity of Hiroshima. I am also both Japanese and American so I think I am particularly sensitized to the issue. But my bottom line is that I was skeptical as I started reading the first few pages.

Continuing with the reading, however, it became clear to me that in some ways there actually are odd parallels between Japan and Brazil in terms of their lasting fascination with their respective “catastrophes”. Moving forward from the bombing, Japan viewed itself as a victim of World War II, and consequently has channeled much energy into tying it’s national identity to the concept of peace. For Brazil, the loss of 1950 was a manifestation of Brazilian’s underlying worry that they “were naturally a defeated people”(55). As large scale, public example of the country’s “stray dog complex”(55), the game of 1950 solidified Brazil’s national identity as one of a people destined to fight an uphill battle against their inherent bad luck. The most painful piece for me was when I read how the Maracana stadium “gave Brazil a new soul”(46) as it attempted to establish itself in the modern world. I don’t know if Bellos adopted some melodrama himself in assessing whether the game caused or was the cause of Brazil’s upward battle mentality, but importance of the game in Brazilian history is certainly not lost.

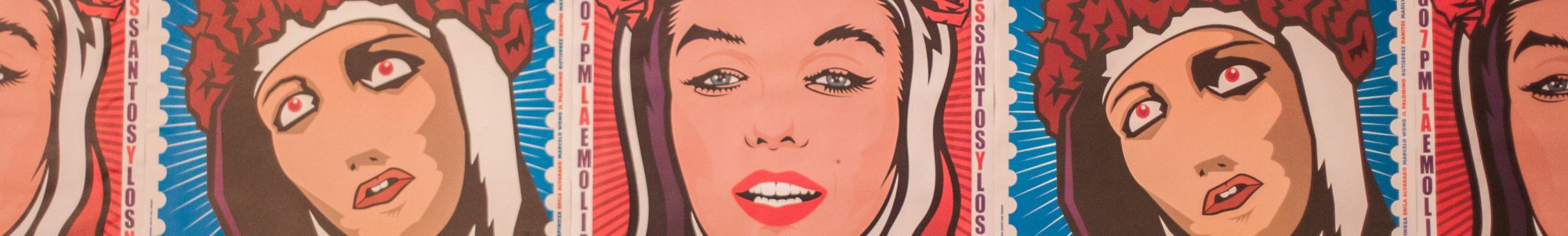

The Ortega reading gave me a new respect for the Telenovela. At home, my family used to sometimes turn on Univision, and I was never able to get over my sensitivity to the cheesiness of the shows. I was unaware of the role that Por estas calles played in shaping Venezuela’s national identity or political climate. It was striking to me that the show was not totally censored for contributing to the volatile political climate.

Collectively from the two readings, I have realized that melodrama is not something to be seen necessarily as a negative thing, since it can play a crucial role in the development of identity in a way I did not previously recognize.