Marcos and the EZLN

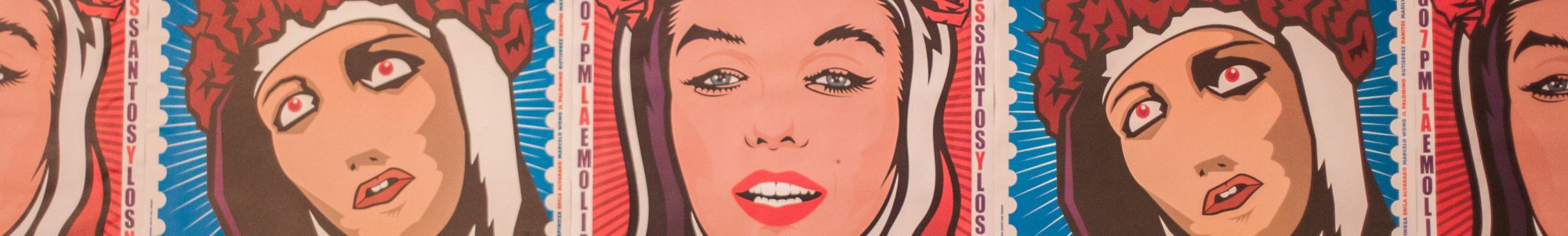

Guillermo Gomez-Pena’s article on Sumcommandante Marcos and the 1994 Zapatista resistance in Chiapas resonated with me on two levels. First, mythic resistance figures to me scream popular culture. You can’t walk twenty feet without seeing either a real-life or fictional example on someone’s shirt (Che, Bernie Sanders, Rosa Parks, Luke Skywalker). When discontent brews within a sector of the population, these leading figures become public templates for the people to imprint their hopes for a better future onto. Much in the same way that the Zapatista adoption of the ski mask enabled Mexicans to see themselves in the face of Marcos, similar figures become idealized figures, gaining a level of anonymity similar to that of Marcos simply by separating their public lives from their private. We don’t know what Che ate for breakfast, we don’t know if Elvis showers in the morning or at night. This public anonymity creates space for popular movements, defined more by the people and their discontent than any single figure at the front.

Second, this article interests me as not the end of popular culture and the movements it inspires but as rather the first tentative steps into a new form of popular culture. The hybridization that Canclini talked about in his article is here the source of Marcos’ hold on the popular. Close control of his public image in the media enabled Marcos to cultivate an insurrection. His failure to hold the attention of the public demonstrates the movement of popular culture into a new age. Marcos, I believe, was ahead of his time. In the internet age, popular culture entirely revolves around popular personas (we have one as the ‘president’ of the ‘free’ world for fuck’s sake). It is also possible, however, that Marcos would be entirely unable to maintain anonymity were his movement to happen now. Regardless, the rise and fall of Marcos from the public eye marks – at least for me, in the context of this class – a distinct shift in the form and attention (span) of popular culture as it entered the 21st century.

I see this Zapatista movement and the image Marcos cultivated in direct contrast to Peronism, interestingly enough. In Argentina, Juan and Evita cultivated their own images based on ideals that would resonate with the people, rather than allowing the people to see themselves in the couple. Perhaps they knew that these mythic figures were doomed to fail, at least in their own lives. For people, even in discontent masses, are afraid of change. As the article puts it, the Zapatista movement spiraled out of the spotlight because a “‘vote for no change’ was in fact a ‘vote of fear.'”

Cultural Identity and Salsa

A question I found myself asking when reading this article harkens back again to our discussions of hybridization and hybridity; when does a culture cease being what it is and become something new? And, more specifically, does an adoption – or translation – of a cultural practice into a new context carry enough weight to change the culture the practice originated from?

According to Canclini’s arguments about hybridization, the first question is truly pointless. With cultures constantly in a state of flux, there are no static cultures to measure against. Yet, on perhaps less nuanced terms than Canclini is dealing with, I found myself pre-occupied with the question in the context of Salsa dancing; When does Salsa stop being ‘Latin,’ and become ‘Latino-British’? To a certain extent it was always ‘Latino-British’ because it inherently carried the latent ability to be adopted into a British context. But it was also never ‘Latino-British’ because that as soon as Salsa dancing became that, it ceased to be ‘Latin.’ Interesting.

The second question – can British interpretations of Latin culture have an impact on Latin culture itself? – I find even more interesting. You could argue that the process Ortiz names ‘transculturation’ comes into play here. Transculturation implies both a cultural inflow and cultural outflow, where a practice shared by more than one culture acts as a sort of tug-of-war between the two (although not exactly reciprocal). But could a relatively niche London Salsa scene have an impact on something as monolithic as “Latin American Culture.” It certainly informs people’s perceptions of it – both people who participate in London’s scene and those who witness it – and that’s an impact, however small. Either way, I do not see this as the end of popular culture, just a step in its widespread globalization.

jLO

When has popular culture not revolved around fetishes? I would argue that objects of popular culture are just that, objects. Of course they exist in another realm. Jennifer Lopez exists as a talented and successful actress, as a woman, as a human being. But popular culture has turned her into an object. As it has done with so many others. Many forget that Justin Beiber, when he blew up, was a sixteen year old with the ability to write and perform pop hits. Drake is like 50 and he can’t even do that. All people saw Beiber for, though, was his hair. It inspired a regrettable hair trend that seventh grade me definitely did not participate in.

Jennifer Lopez’ identity as a Latinx actress does play an important role in this. Her fetishizement in the eyes of the popular, however expected, marginalizes her as a representative of an identity that is constantly being marginalized. While Beiber and his hair moved into the realm of popular object, you could rely on ten million other white guys with guitars to fulfill any need you could have for white guy representation in the music industry. Jennifer Lopez doesn’t have that luxury. Hollywood especially hasn’t represented Latinx identities particularly well, and objectifying jLO doesn’t exactly help.

The end of popular culture? I’d again say no, that popular culture has done this before and will continue to do this until the end of time. But perhaps it is not in the realm of popular culture that Hollywood – and the media in general, to be really oblique – needs to strengthen its representation of Latinx identities, so that jLO’s butt can win TIME Magazine’s Person of the Year without further marginalizing cultures that have been shoved to the side of the road again and again.

).

).