I really, really enjoyed the reading Futbol this week! I felt that’s what I had in mind I would learn about when I signed up for this course, so it felt good we finally were ready to learn about football and telenovela culture.

I had read and heard numerous time that football is akin to “religion” in Brazil, but I feel I had still underestimated how magnanimously important the sport is for Brazilians. Brazilians compare the loss at the 1950 World Cup (the Maracanazo) to the bombing of Hiroshima. The event is touted as the single worst national tragedy in Brazil’s sovereign history. The reason Brazilians were and still are so deeply affected by the loss is not only because of the passion they have for football, but also because a loss was projected by the media as unthinkable, the impossible. Newspapers, politicians, and radios had already hailed the Brazilian players the new world champions. Additionally, there were no televisions, therefore, most of the Brazilians had paid to watch the team play live, and thus watched the heartbreaking goal scored by Gigghia right in front of their eyes too. It was an image that never faded away from their memories. What made the loss worse was that rather than brushing off the defeat as a freak result, the Brazilians accepted it as something they “deserved”, that the “Brazilians were a naturally defeated people”. The loss reinforced a sense of inferiority and shame.

But putting aside the heartbreak of the general populace, the three players to suffered the most in the event’s aftermath were Barbosa (the goalkeeper), Bigode and Juvenal, coincidentally, all of them black. Therefore, the event reignited theories that “Brazil’s racial mixture was the cause of a national lack of character”. I really empathized with these three players while reading the text. The entire blame for the defeat fell on Barbosa, who was never allowed to forget 1950. He was labeled as “the man that made all of Brazil cry”. I cannot fathom how difficult and heartbreaking it must’ve felt to be made to feel the cause for millions of heartbreaks. Despite being voted as the best goalkeeper during the 1950 World Cup, he was shunned by his colleagues and called bad luck. Zizinho, another member of the 1950 Brazilian squad, described how adversely the event affected Barbosa, Bigode, and Juvenal. Bigode didn’t leave his house and Juvenal left Rio for good. It’s even sadder to realize that much of the reason why the blame fell completely on their shoulders was because of their skin colour, and not so much their football. It’s also interesting how, even though Zizinho says he moved past the event, he still has drawings of football systems lying around in his house. None of the players, even half a century later, were ever able to really put the fateful match behind.

Also, it was really interesting to find that Aldyr, the man who designed Brazil’s characteristic yellow football uniform after the 1950 World Cup, actually supports Uruguay, the team that caused the need for his design in the first place. Not only this, but Aldyr doesn’t particularly take much pride in his creation. I mean, sure he grew up on the Brazil/Uruguay border, and that explains his love for Uruguay, however, he literally is the designer of the most recognizable and famous jersey in sports!! Forget gloating, he doesn’t even take any pride in it?!

Finally, it was interesting to read what Gigghia, the guy who scored that fateful goal, had to say about the event. He is the poorest of all the surviving 1950 veterans, quite an irony. As much as I right now sympathize with the Brazilians, he deserved better treatment from the Uruguay government. He doesn’t feel much guilt for scoring the goal, but that’s hard to believe. That single goal he scored thrashed millions’ of people’s hopes, morales and self-esteems. He literally is the cause of Brazil’s Hiroshima. The worst part though is that the team that won that day, Uruguay, no longer remembers the much about the event, “In Uruguay, [they] lived the moment. Now it’s over.” But 5 years later, in Brazil, they “feel it in their hearts every day”. Actually, in hindsight, it was overall a very fun sad read and Barbosa deserved more love. I think I got too into it …

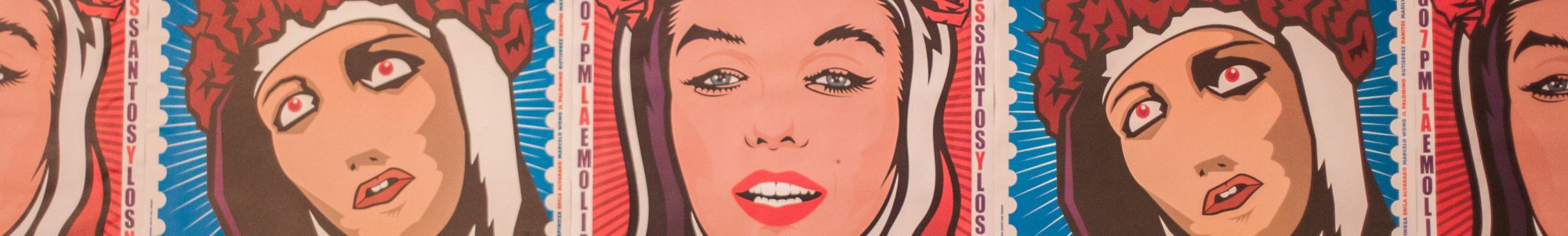

It was also very interesting to read about the Telenovelas produced in Latin America. Telenovelas are different from American soap operas in that while soap operas are driven by money and sex, telenovelas revolve around more family-oriented concepts, i.e. falling in ove, marrying and having children. It reveals a lot about the culture of Latin America, and what they value the most in life. Unlike soap operas, telenovelas also have a beginning, a development and an end, “because its goal is to “solve” life and provide it with a happy ending”. Ortega discusses Venezuela’s “Por estas calles” at length as an example of a modern telenovela and its theme, structure and characters and genres. The show was so interwoven with the national/political events in Venezuela, that it never enjoyed the same success in other countries that imported it. It was “too foreign” for them, highlighting how telenovelas are usually centred around contemporary political, affective and social issues.