Two issues therefore arise:

First, the mechanisms of encoding. These are perhaps successive. For instance, what happens as pain is expressed or transmitted first affectively (paradigmatically, in the scream; see John Holloway on this), then narratively (say, in testimonio), and then as a legal plaint (taking rights discourse to be a version of juridical deliberation)? How, in other words, is the discourse of rights produced? Looking at this would involve understanding the ways in which struggle and repression become encoded, enter into various types of representation. I think it's out of a concern with this process that Deleuze argues for the importance of jurisprudence:

Creation, in law, is jurisprudence, and that's the only thing there is. So: fighting for jurisprudence. That's what being on the left is about. It's creating the right.One would have therefore also to think further about the theory of representation at work here. Deleuze argues in terms of "creation" rather than a perhaps more customary emphasis on the dislocation between referent and sign.

One would also consider all the various groups, institutions, and (in short) agencies in all senses of that word that contribute to the mechanics of rights discourse: the role of human rights groups, for instance; or the relays between international bodies such as the OAS or the UN; or the part played by truth commissions and the like.

Second, however, why think of rights discourse as the final text, as an end product? Indeed, though rights as often presented as goal as they are assumed as origin--hence the notion of "fighting for" or seeking to gain rights--it's surely best to see them as an instrument, as one more cog or chain in a much broader arrangement. After all, does anybody really care about the right to (say) shelter, privacy, or free speech? No, they care for the achievement of those goals. In rights discourse, this is finessed as the distinction between an exercised and an unexercised right; but an unexercised right is dead, useless.

What then (and here I'm inspired by some discussion at Serena's blog) of rights discourse as one part of a broader mechanism of social justice? Rights here (as Peggy implies) would be the abstract moment bridging two concrete practices: crime and its punishment.

A few concerns:

First, all this sounds worryingly dialectical, as the abstract universal mediates concrete particulars.

Second, would the above not also apply to law tout court? (What difference is there between rights and law? Are rights not just a (fictitious) model for an entire legal constitution?)

Third, such talk of mechanisms seems to obscure the importance of interpretation.

Fourth, we shouldn't forget the sovereign instance (state or divinity, or even the idea of the human) that ultimately guarantees the possibility of any such mediation.

OK, for a moment there I thought I might be on the road towards salvaging rights, now as mechanism rather than discourse. Perhaps not.

But it might be worth figuring out how the machine of rights discourse functions, and how it compares with the machine of state power or sovereignty.

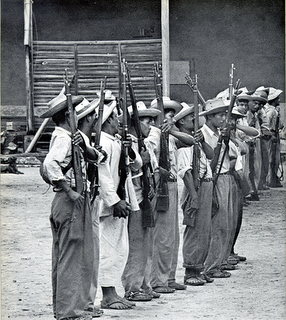

But it might be worth figuring out how the machine of rights discourse functions, and how it compares with the machine of state power or sovereignty. Reading about the 1954 Guatemalan coup, I'm struck by how much what the CIA cobbled together was a Heath Robinson contraption (Rube Goldberg machine for North Americans) constantly in danger of breaking down, but finally anchored by US President Eisenhower's say so.

How different is that from (what would be more charitably described as) the network by means of which human rights abuses are charted, publicized, and acted against? I'm thinking here for instance of Amnesty's decentralized collection of letter writers, assiduously (as I imagine them) sending postcards off to jailors and generals throughout the Third World. But again, does this network not also depend upon a sovereign instance as anchor?