Monthly Archives: November 2011

Case Study Guatemala II

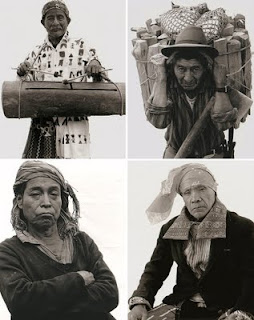

This week we continue our examination of Guatemala. In this selection, author Victor Perera outlines his efforts to discover evidence of army activity in the country’s western highlands known as the Ixil Triangle (aka Operation Ixil) , and the resulting findings. This operation was said to have taken place between 1978 and 1983, and to have resulted in the deaths or displacements of at least “25, 000 Ixil residents of Mayan descent” (p 62). If the allegations made by human rights and church groups were true, then the Operation would basically have been a genocide.

The Ixils had been used by the Spanish colonists as cheap labour when the coffee plantations arose in the late 19th century, and the legislative enslavement of the indigenous migrant labour has remained basically changed until today. In other words, the rights of the Ixils have been violated for a long time. They were ‘recruited’ by contratistas who were charged with hiring as many labourers for the coffee plantations as possible, often using liquor or debts as a way to basically force the Ixils to sign up.

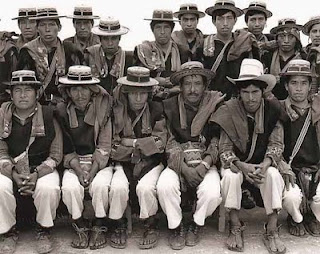

Ixils themselves are not the only ones who have been enraged by the treatment they have received. Two Spanish priests, Fathers Xavier and Luis Gurrurian were appalled by the exploitation of the Ixil labourers and between 1955 and 1975 worked to establish agricultural and craft cooperatives, installing indigenous people as the heads of them. However, in 1975, the army identified them as Marxist subversion, despite many of the priests’ alliance with anti-communism. Although the priests ended up needing to flee the area, the army could not stop the peasant labour movements which had emerged in the Ixil Triangle from the priests’ time spent there, the largest of which was called the Committee of Peasant Unity, or CUC.

The CUC’s major concerns were the treatment of Mayan workers in the highland coffee fincas and the working conditions of ladino and indigenous peons on the West coast’s sugar, coffee and cotton plantations. One human rights violation that frequently occurred on these plantations was the illegally frequent spraying of DDT on cotton plants, which caused hundreds of workers to die from liver and lung diseases, as well as infiltrating and intoxicating the breast milk of nursing mothers. All of this and more led to several strikes in the 1970s, which ended up succeeding in that the minimum wage was raised (to $3.20 daily), but many employers found ways to avoid this law, and most coffee and cotton workers only ended up collecting about $0.80 to 1.00 daily. From these examples, it is clear that the Guatemalan property and plantation owners were majorly taking advantage of the indigenous peoples, who were either willing to work for little wages due to their prior living conditions, or forced into it in some way.

Case Study Guatemala I

The selections for this week were focused on the United Fruit Company, or la frutera as it was known in Guatemala. United Fruit was an American company based in Guatemala, and basically dominated Guatemala’s international commerce from the 1800s and still has a presence today. The concept of human rights comes up a couple times within this selection. On page 71, the living conditions and situations of the workers employed by United Fruit is discussed. Basically, the employees had better living conditions and pay than many other Guatemalan labourers. However, they were basically dependent upon the company, including living in the which made a disproportionate profit from conducting business in Guatemala, then selling the product in the United States. The company is described as “benevolent and paternal” (p 71), a term reminiscent of colonists and missionaries who ‘know what’s best for the people’, etc. Indeed, United Fruit provided housing and medical facilities for their workers as well as education for the employees’ children. However, the company’s employees worked seven-day work weeks, and the company continually refused to allow their workers to join any kind of independent labor union, and for a time I’m sure they were okay with that due to the benefits that they received from the company already. However, in 1945, Jose Arevalo’s administration began to target United Fruit, and strikes broke out, with workers demanding better pay and working conditions, fuelled by the Labor Code of 1947. In fact, at one point the Labor Code almost motivated United Fruit to withdraw from Guatemala.

Many Guatemalans were aware of the negative affects that United Fruit had upon their country. The Minister of Labor and Economy believed that the company was “the principal enemy of the progress of Guatemala, of its democracy, and of every effort directed at its economic liberation” (p 73). It seems as though the company had the country in a economic hold, as it had managed to make deals with a great number of politicians which did seem to impede the country’s progress, for example, their deal with General Ubico, who signed a 99 year long deal with the company which guaranteed them “exemption from internal taxation, duty-free importation of all goods and a guarantee of low wages” (p 70). Ubico seemed to think that the benefits the company would bring to Guatemala would outweigh the accompanying drawbacks, as well as probably wanting to extend good relations with the United States, an obvious international power.

Indeed, the matter of the United Fruit Company in Guatemala became an international issue. In an effort to undermine the Guatemalan government, United Fruit officials informed the American government that there was a possibility of communist influence in Guatemala. President Eisenhower appointed ‘The Liberator’ of Guatemala, Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas, and the CIA dispatched 170 troops to Guatemala through Honduras. Meanwhile United Fruit was providing the US military with access to its railroads, its communications systems and even places to stay on its properties in order to counteract the rebellious forces. This entire process led to a coup in 1945, and afterwards the United Fruit company lost its power within Guatemala, as the government of the US had lost its faith in the company, and without that they could not continue on the same level as before. All in all, the United Fruit Company had an unfathomable impact upon the citizens of Guatemala, mostly due to it bringing the country to international attention and linking it to the United States.

Nov 21 – News Article

Peruvian authorities reopen investigation into forced sterilizations

In this article, Rafael Romo discusses the number of women who were unwillingly and unknowingly sterilized during Alberto Fujimori’s presidency in the nineties. The special prosecutor investigation the issue, Victor Cubas, estimates that there are thousands of undocumented cases of forced sterilization, and at least 2000 documented cases. These investigations were opened first in the years following Fujimori’s term, but were shelved in 2009 by Alan Garcia’s government. It wasn’t until Ollanta Humala was elected in July that the investigations were ordered to be opened up once again. Under Fujimori, doctors, gynaecologists and nurses had a quota to fill, consisting of sterilizing three women a month. Marino Costa Bauer, the Peruvian health minister between 1996 and 1998 insists that although the campaign was ‘perhaps’ poorly executed, the sterilizations were all voluntary, citing many signed documents as proof. However, a woman says that she and her husband were forced to sign such a document, indicated that even if there was signed consent, it was not voluntary. Costa Bauer also denies that this campaign targeted poor, indigenous women in isolated communities, although human rights groups have insisted that this is the demographic that seems to be mostly effected.

Gunmen Execute Indian Chief in Western Brazil

This article illustrates the age old battle between land owners and Indigenous people in Latin America. In this case, gunmen hired by cattle ranchers were sent into an Indigenous village in the hope of brutally repressing land claims and getting the people to move. Evidently, the more tims go on, the less things change.

Gunmen Execute Indian Chief in Western Brazil

This article illustrates the age old battle between land owners and Indigenous people in Latin America. In this case, gunmen hired by cattle ranchers were sent into an Indigenous village in the hope of brutally repressing land claims and getting the people to move. Evidently, the more tims go on, the less things change.

The Right to Truth

Recently I have been wondering about the theme of Truth Commissions and what some people have called the right to truth. If it is truth as it has been argued that the rights to truth is a fundamental component of international humanitarian law, particularly when gross violations of human rights have been committed. In Brazil, president Dilma Rousseff has established a Truth Commission that will look into the human rights abuses and disappearances that occurred during the military regime that went from 1964 to 1985.

Six commissioners who beyond subpoena powers will not be able to prosecute or recommend charges against the perpetrators of the human rights violations will integrate the Commission. Although, it is an interesting discussion to have, namely what is the purpose of having a truth commission if there are no prosecutions, not even under transitional justice parameters, particularly when the existence of the Commission is premised on the right to justice. But again it seems that if there was a fear of prosecution the Military will have not supported the creation of the commission.

Even if one disagrees with a truth commission with a sanitized sense of justice, it seems an interesting discussion to have. On the one hand, one could argue that it is a purely bureaucratic endeavor, which only aims at saving face, but that lack of prosecution could also open the door for confessions that would have not emerge if the fear of prosecution was present.

Human Rights and Trade with Columbia

The above article is simply about how Columbia is trying to bolster trade with England and show itself as an economic power in Latin America. What’s really interesting about it is that England has said that they will sign a Human Rights agreement with Columbia as part of starting to trade with them. It was pointed out in another article on the topic that England has put Human Rights at the forefront of it’s international policy (so it says), but Columbia is accused of some of the worst Human Rights abuses especially against trade unionists. It will be very interesting to see what the Human Rights agreement actually says when it is signed by the two countries as trading partners. It is one thing to have a bilateral trade agreement but it is very interesting to see a bilateral Human Rights agreement as well.

The ‘Christian’ Sides of Conflict

While this week’s readings highlight many interesting thing about the Guatemalan military conflict in the Western Highlands, one thing that really struck me was the ‘battle’ between evangelical and catholic forces and how those two branches of christianity played so heavily into different sides of the conflict.

Obviously, missionaries have been a persistent force in Latin America since the arrival of European colonists. Also, the ‘christainization’ of indigenous peoples has been shown as a ‘justification’ for colonization many times. However, it is interesting how this piece highlights that the evangelicals and the catholics were distinctly on the side of either the military or the EGP.

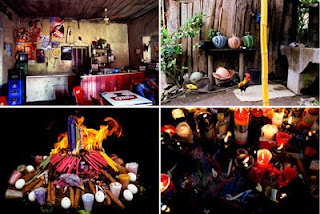

Interestingly, it was the strong community bond of the Ixils which was bolstered by Catholic Priests which drew the EGP to the area in the first place. From there on out the catholics seem to be synonymous with people who are in the EGP and as a ‘communist’ force in the area. It’s interesting how the priests felt the need to intervene on more than a religious level in order to start socially organizing the people in political ways, like how Father Xavier created the indigenous agricultural and craft co-ops. On the other side, the evangelicals are helping to sponsor the military and to invest in the landowners who are going bankrupt. One incredible example of the evangelical example is that of Luis Arenas who had the audacity not to really pay his workers, but to still accept money from christian groups abroad as the representative for ”Americans for Freedom in Central America.”

It is fascinating to look at the discourse on both sides of the aisle. On the Catholic side it seems to be that the priests and their well intentioned initiatives are just portrayed as part of the cause adding to EGP power. While it’s probably safe to say that the ‘progressive’ actions of the priests were intended to provide solidarity to the indigenous people, it would be very interesting to see if they actually intended to become so tied to something seen as a ‘guerilla’ movement. As described on page 86 the catholics went from being conservative, to a ‘progressive’ christian base to being regarded by the military as “hotbeds of insurgency.” I find it hard to believe that the priests truly wanted to be so polarized in their work; however, they found themselves so tied to the EGP that they eventually had to leave the area for a period of time.

The rhetoric surrounding the evangelical movement is slightly disturbing. If you think about it, “Americans for Freedom in Central America” could easily be a slogan on Fox news tomorrow just replace Central America with Middle East, or actually you might not even need to change it. These kind of campaigns always seem to be dangerous and the idea that foreign investment in militarized regimes so easily follows such campaigns is alarming. It also should be noted in this piece how every time an evangelical group was mentioned, so too was their funding source. Some came from landowners gaining investments from abroad, others came from “reformed real estate brokers” etc. Then of course the percentages of people subscribing to one religion or the other is noted as well, as if it too were an economic statistic. Of course, President Regan gives his blessing to the movement as well showing the presence of reganomics within the situation.

Essentially the idea of catholics alining with co-ops and evangelicals with investors shows how this religious debate is just another factor in the polarization of both sides. In fact, the religious differences between the two sects aren’t highlighted once, just the economic and political differences. This is also demonstrated well in statements, like that about Mayor Guzman, which state that he is an evangelical who still smokes and drinks; this shows that being evangelical had little to do with religious practice and much more alignment with politics.

Overall, it’s interesting to look at how the military verses the EGP is framed. For while they are obviously two separate groups politically virtually everything else, like religion, seems to be polarized around them as well.

Guatemala II

The most horrible thing in all of this to me, however, is the stance of complete lack of responsibility taken by the military as well as it's apparent ease of de-humanizing those that they were fighting against. The victims of this violence were, for the most part, innocents, though they were proclaimed to be affiliated with resistance fighters. And even if they were, who can blame them? The political system was corrupt and didn't care for it's people. There was no food, no work, no respect, people couldn't live, and Indigenous people were treated like dirt. In circumstances like these, I would be part of the insurrection too. But this outlines the danger of the creation of an "us versus them" attitude being indoctrinated. As soon as a segment of a country's population starts pointing the blame at another segment, and takes action against it, all hell breaks loose. I know that this is a long shot, but I can't help thinking of the waves of repression that have begun sweeping Occupy movements, and the brutality of the police forces in general when people try to break loose and defy the status quo. If we can't trust out armed forces to listen to us and protect us, who can we trust?

Guatemala II

The most horrible thing in all of this to me, however, is the stance of complete lack of responsibility taken by the military as well as it's apparent ease of de-humanizing those that they were fighting against. The victims of this violence were, for the most part, innocents, though they were proclaimed to be affiliated with resistance fighters. And even if they were, who can blame them? The political system was corrupt and didn't care for it's people. There was no food, no work, no respect, people couldn't live, and Indigenous people were treated like dirt. In circumstances like these, I would be part of the insurrection too. But this outlines the danger of the creation of an "us versus them" attitude being indoctrinated. As soon as a segment of a country's population starts pointing the blame at another segment, and takes action against it, all hell breaks loose. I know that this is a long shot, but I can't help thinking of the waves of repression that have begun sweeping Occupy movements, and the brutality of the police forces in general when people try to break loose and defy the status quo. If we can't trust out armed forces to listen to us and protect us, who can we trust?

Mexico gives muddled response to criticism of human rights violations amid drug war

“A new report says Mexico fails to limit security forces’ torture, disappearances, and extrajudicial killings in the drug war. But Calderon’s response ‘skirts the issue,’ says blogger Patrick Corcoran.”

Media and Human Rights

This website promotes the use of Tactical Media in Human Rights Movements. There are plenty of interesting blogs about the use of media in Latin America and around the world.

Also an interesting post about the relationship between the media and Human Rights: http://www.newtactics.org/en/blog/new-tactics/engaging-media-human-rights

We need to be interested in “engaging” the media not just as another constituency with some influence, but because it is one of the ESSENTIAL levers of power. The media is integral to civil society. The media — and this may be a worldwide phenomenon — bolsters or undermines progress. It makes or breaks regimes. It fosters, or undoes, a culture of respect for human rights.

"Solo el que lucha tiene derecho a vencer. Solo el que vence tiene derecho a vivir."

I did my case study on the Zapatista Movement in Mexico and throughout the readings this week parallels rang obvious. A few issues of interest out of the readings and my research: [1] Justice through Violence [2] the role of the media.

I guess one of the biggest questions that I have struggled with not only in this class but in all my classes this term is the role of violence in the search for justice and the defense of Human Rights. [and this ties back to last week’s readings as well] The idea that in most cases where there are high levels of Human rights abuses, Human Rights discourse and peaceful dialoguing between parties never seems to be enough. That violence turns out to be the most viable alternative tending to result not only in pushing forward progress and more immediate results but also in bringing the issues to light in a very public and publicized way—as the reading began “SOLO EL QUE LUCHA TIENE DERECHO A VENCER. SOLO EL QUE VENCE TIENE DERECHO A VIVIR” (62). The Guerilla Army of the Poor (EGP) in a single act of violence, executing Luis Arenas in 1975 set in motion the movement that would spark Human Rights discourse in Guatemala.

“From that moment on, […] the word spread throughout the region that the guerrillas were not foreigners, since they spoke the local dialect… and that they surely had come to do justice, since they had punished a man who had grown rich from the blood and sweat of the poor.” (69)

The violence occurring in Guatemala on both sides of the fight—both guerrilla violence and government violence—was able to draw in the interest of the UN and led to the consequent signing of a Human Rights accord in 1994 between the government and the guerillas. In addition the peace talks resulted in the recognition of the Mayan peoples ethnic rights and indigenous identity granting them recognition and limited political autonomy (360).

On a different topic…

I also find the relationship between the media, local and international, and its role in the process of Human Rights defense really interesting. In the reading, the story of Jennifer Harbury and her use of tactical media to both promote her cause and incite governmental action was particularly effective. Her portrayal in the local media, the international media and the controversial signing of the million-dollar movie contract with CNN, although not all positive, all had a positive impact on her cause and ultimately allowed her to succeed insofar as she attained the information she was looking for—outwardly stating that she was very happy about the movie contract as it would keep the spotlight on human rights abuses in Guatemala and the fact that she would be able to use the revenues to fund aid to Mayan widows and other victims of the war.

The Zapatistas also used tactical media very impressively – Subcomandante Marcos was able to draw international support for their cause. One of the most peculiar examples of this is his appearance in the French Marie Claire.

It seems that within any movement for Human Rights media coverage is incredibly critical.