The Mark of Zorro (1920): The fabrication of freedom and the cultural hero

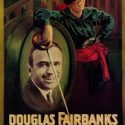

One of the neat things about studying older films such as the Mark of Zorro (1920), a silent romantic film starting Douglas Fairbanks, is that it gives the attentive viewer an opportunity to travel back in time and see the origins of how adventure and heroic movies were made in a time when the movie industry in Hollywood was in its infancy. For instance, this movie allowed Fairbanks to become a much more popular and richer actor than what he already was since its production company, Douglas Fairbanks Picture Corporation, was created then to catapult him into an action figure adored by millions of his loyal audience. Hence, the script of the Mark of Zorro, which was originally published in the magazine “All-Story Weekly”, was based on the story, “The Curse of Capistrano” by Johnston McCulley and adapted into a movie script to suit Fairbank’s athletic skills. All of these background and historical information serves to point out that we as movie critics need to be aware of the purpose and intention when watching a movie.

I talk about intention in movie making just to bring up a subject which sometimes escapes our attention when watching a movie for the first time. Why are movies made and do they challenge the status quo or, on the contrary, reinforce it? In the case of the Mark of Zorro, directed by Fred Niblo, these questions are of great importance given that in 2005 the United States Library of Congress selected this film for preservation in the National Film Registry, giving it the status of “culturally, historically, and aesthetically significant” (Mike Barnes, 2015, The Hollywood Reporter). With this movie, the Mark of Zorro, the sword fighting devil-may-care adventure hero was born. Seeing the mistreatment of the peons by rich landowners and the oppressive colonial government, Don Diego Vega, son of a wealthy hacendado Don Alejandro, takes the identity of Zorro, a Robyn Hood-like character who makes life miserable for the rich and powerful rulers of old California in the early 19th century and fights off oppression. By definition, Oppression is a “prolonged cruel or unjust treatment or control” of people, and this is exactly one of the reasons why this movie was made. Audiences back in the 1920s needed new reasons to keep going to see movies and the Mark of Zorro played on the idea of “freedom for all” and “justice of all” type mentality which most Americans adhered to at the time and still do in the present.

Nevertheless, it is important to go further in the exploration of the plot and the main character of the Mark of Zorro and perhaps come to a better understanding of why action movies are so important in the present and the social and cultural implications that movies such as this one leaves in the minds of audiences around the world. The beginning of the movie starts with a screening sing which says, “Oppression by its very nature creates the power that crushes it”. Therefore, while this may have some truth to it, the movie hints directly to the need of the creation of a hero-like person such as Zorro, a within-the-system champion who is the only one who can rise to defend the oppressed of lower rank and status. Zorro, a high-born of Spanish decent and education, does not belong to the lower classes (being these Mexican or American Indians), nor can he be a mestizo (those of mixed Indian and Spanish blood or culture) but only by a Criollo (those of Spanish descend born in the New World) just like Don Diego Vega is.

Hence, the question of freedom from oppression becomes a question of class, culture and social justice which does not include all peoples. The Mark of Zorro (1920) hints first to the independence and then the annexation of California to the United States under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848), following the defeat of Mexico in the Mexican-American War. Additionally, this movie also points out to the Wars of Independence that many Latin American nations had at the beginning of the 19th century against Spain. One way or another, the newly republics from the very beginning abolished the formal system of radical classification and hierarchy (at least on paper), the Caste-System, the Inquisition and novel titles. Slavery, on the other hand, was not abolished immediately but ended in all the nations within a quarter century. After watching the Mark of Zorro, however, one cannot undeniably come to the conclusion that the movie contains a political message favoring the creation of new nations, as well as the separation of old California from Spanish ruling, were defenders of Oppression such as Don Diego Vega and his alter-ego Zorro, preserve the status-quo by belonging to the Criollo elite at the top of the social hierarchy system.

Within the movie itself, there are a few interesting observations which are important to expand. The main character, the young Don Diego Vega contrasts directly with his heroic alter-ego, Zorro in many ways. First, Diego appears to be a contrasting opposite to Zorro given his apparent disinterest in war, weapons, and sword-fighting. However, it is clear that the viewer would distinguished that this is a cover up by Don Diego to justify the plot. The idea of hombria or manhood is well-established in the movie by contrasting the sword-fighting abilities of Zorro against the soft-handed approach of Don Diego and his liberal education in Spain. The idea of fighting and defending one’s nation is directly linked in the film to virility (the sword is an extension of a man’s manhood’s; in other word his penis is his sword), agility, romance, freedom fighting, nobility of blood (in the case of Don Diego his lineage can be traced back to Spanish blood purity). Then, The Mark of Zorro is a sort of Scarlet Letter for the sinful oppressor and cruel rulers of old California. Hence, the marking of the ‘Z’ by the hand of Zorro on one’s body (or face) is the branding of injustice and the social exclusion and perhaps rejection by the rest of the population whom align with the freedom seeker of the movie. Only when Zorro proves his sword-fighting skills, his ability to get the girl (a returning theme within action movies), his unmatched athleticism, and most important of all, his purity of blood by demonstrating to all the other Caballeros his Spanish lineage, is only when Zorro is allowed to become the leader of the revolt against the Governor and gain independence against the colonial Spanish ruling.

As a side note, and not less important than the analysis of the main character Zorro, the character of Lolita Pulido (Marguerite de la Motte), a typical damsel in distress, does not challenge the stereotypical female role of the time and instead conforms to getting married to the rich guy and please her parents. In the movie, there is a scene in which Lolita seems to be waiting in the living room of Diego’s town house with a book in her hand, and she does not read it but only flips through the pages of the book while waiting patiently for her hero to appear. For this reason and many others, Lolita Pulido represents the typical female supporting role which only exists in these types of movies to fulfill the role of the principal male character and which is very important in the eyes of the audience. When Captain Ramon says, “Beauty should not be cruel”, he is saying, women should not be aggressive, nor fight for their rights or defend themselves against aggression. Hence, leaving the role of rescuer, hero and saviour to only Zorro.