The Indian Act was created and set into effect in 1876, nine years after Canada was “created” in 1867. The act enabled the government control over First Nations Indian status, resources (such as where they were able to hunt), wills, education, land, and band management (Montpetit, 2011). The objective of the Indian Act was to assimilate as many First Nations as possible, excluding Metis and Inuit, into an idealized British-Canadian society. For example, under the Indian act First Nations women who married non-status men would automatically lose their status, the government’s way of robbing of identity and ensuring forced integration. Indian status was “seen as a transitional state, protecting Indians until they became settled on the land and acquired European habits of agriculture” (Henderson, 2006).

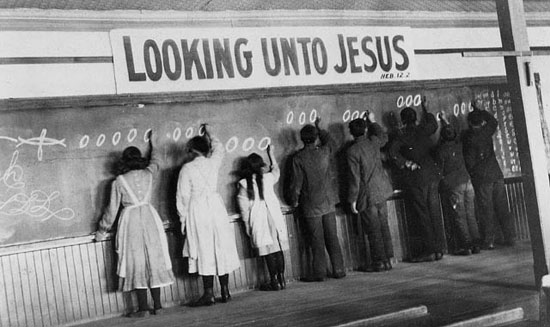

One of the most horrific outcomes from the Indian act of 1876 was the use of residential schools, which were in operation from 1879-1996 (Montpetit, 2011). As intended, the schools forced many First Nations children to forget their language and culture, as well to suffer frequent verbal and physical abuse. Here is a very explicit account from one woman of the abuse she endured when she was forced by the Canadian government to attend a Residential school. Her story is akin to many First Nations who recount their lives at these schools. Unfortunately, Canadian government propaganda attempted to justify the schools through ads such as these which completely dissimilar to the accounts told by First Nations people themselves.

Canadian Residential School

Since 1876, there have been many amendments to the Indian act as well as the Canadian Constitution that make it possible for First Nations to control their own lives and identities. In 1982, the government amended the Constitution so that those First Nations who had lost their status through marriage because of the Indian Act of 1876, were now able to be reinstated as status First Nations / band members along with their children (Henderson, 2006).

After my research, I conclude that the Indian Act of 1876 was a way for the Canadian government to justify forced robbery of First Nations identities and control over an entire race. The idea that author Daniel Colman discusses is of English-Canadian identity being tied up with an exclusionary model of British civility and masculinity. Colman argues that colonials, nation builders, and the government were fixated on ways to “formulate and elaborate a specific form of [Canadian] whiteness based on the British model of civility” (Colman, 5). However, as Coleman demonstrates, the code of civility was inherently based on a racist assumption of white priority, where “others”, such as the First Nations, could be accepted as long as they modeled themselves according to White British values. Hence acts such as the Indian act of 1876 which aimed to completely strip First Nations people of their original identities and assimilate them into a British-Canadian culture so that Canada could be seen as one great homogenous nation.

Works Cited

Coleman, Daniel. White Civility: The Literary Project of English Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. 2008. Print.

CTV. “Accounts of Residential Schools Continue”. Youtube, March 1, 2012. Web, Febrary 27, 2015. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L3i_ootZDgM>

Henderson, William. “Indian Act”. The Canadian Encyclopedia. 2006. Web. February 27, 2015. < http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/indian-act/>.

Montpetit, Isabelle. “Background: The Indian Act”. CBC News Canada. CBC News, May 30, 2011. Web. February 27, 2015. <http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/background-the-indian-act-1.1056988>.

PenTV. “Canadian Residential School Propaganda Video 1955”. Youtube, May 2, 2009. Web, February 27, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s_V4d7sXoqU.

Stout, R (2010). “Residential School” [Image]. Retrieved from http://www.mediaindigena.com/roberta-stout/issues-and-politics/residential-school-money-has-it-helped-survivors-heal.