Trends in Education

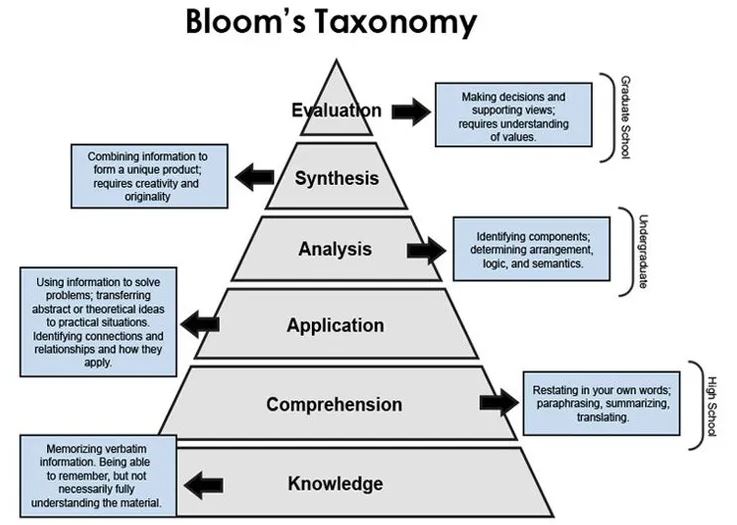

Trends in Education tend to come and go, but what hasn’t really changed is how humans develop. We continue to gain a better understanding of how the brain and the process of learning works, but the simple idea of developmental stages of human development has been fairly consistent and universally accepted. Piaget’s law of conservation is an example and few question its validity. Bloom’s taxonomy is another universally accepted tenant of education and according to a 2019 posting on the website TeachThought it still ranks at the top of educational inquires and trends. Both of these examples support the idea that before any higher order thinking can occur, knowledge must be in place.

Trends can often become fashionable and in the zeal to apply them, they can over shadow established understandings and this is what I have been noticing in education as of late. The intent of constructivist learning theory or experiential learning is solid, however when discovery learning is promoted as the answer to all of public education’s problems, and then educators go “all in”, they often do so at the expense of limiting crucial background knowledge acquisition.

Kids are Kids

I have witnessed, both in my own practice and that of my colleagues, that when students are asked to discover or learn on their own, if they do not have the requisite prior knowledge, then the endeavor is largely wasted. Recently, a colleague was describing his attempts with direct, guided and pure inquiry learning with a Socials 11 class. His first focus of study was teacher directed. Students had no choice in what they were being taught, but were still engaged and effectively “learned”. His second focus gave students a choice and after giving them minimal background information he “guided” them towards his learning objectives. His last focus was purely independent and students chose their topics, submitted required plans and outlines as to how they were to proceed, and when left to their own devices, that is what literally happened; they went to their devices. Most (not all) 17 year-old students were unable to utilize their time effectively and despite constant reminders, warnings and prep work to ensure students knew what they were to do and how they were to go about it, they wasted learning time on their phones, socializing and generally procrastinating and avoiding work. In the end, the majority of the project work handed in was of poor quality and was obviously complied, assembled (and in some cases) plagiarized at the last minute. This scenario is similar to comments made by colleagues in different subject areas and in different schools. My own personal experience suggests that the younger the high school student, the more ineffective their project-based learning was. In the end, as Kirschner, Sweller and Clark suggest, and as my colleagues are discovering, it was the direct instruction that was most effective and efficient (Kirschner/Sweller/Clark, 2006), and it was the inquiry projects that were the least effective and the most time consuming.

Teenagers are teenagers and they lacked the emotional maturity and the intrinsic motivation to effectively manage their own learning. We understand developmental stages and we understand the predispositions of social and emotional importance teens possess over logical reasoning (Dahl, 2004). We institutionalize that understanding with a whole host of laws and understandings such as rules around the consumption of alcohol, voting and the requirement of graduated driver licensing, but I feel that we tend to disregard these facts when we assume that all teenagers can be intrinsically motivated to be responsible for their own learning in all subjects that are required and offered in high school.

“You Cannot Think Critically About Something You Know Nothing About”

There are other examples of large amounts of inefficient learning time being under-utilized by adolescents and other examples of self-directed learning that goes awry when students lack adequate background knowledge. Another personal example was of a Social Justice 11 teacher in my school who at the end of her course provided a list of topics for kids to develop a Capstone project. One student chose “racism” and when the final project was handed in, the paper was full of misinformation and misunderstandings. The student’s bibliography was peppered with questionable Youtube videos and what can best be described as “alt-right” websites. The sad part of the whole experience was like what Froehlich says that; “Once acquired, false information is hard to dispel” (Froehlich, pg. 24, 2020). In this example, the student had a small amount of background knowledge that lead them into a wrong direction, and like a textbook example of Dunning-Kruger, was convinced of their competent knowledge. Effectively, the student was unable to think critically about something that they really knew little about.

Schools Should Become Bastions of “Truthful Knowledge”

In an era of almost unlimited amounts of misinformation and an era of almost universal access to disinformation, public schools need to focus on more effective, efficient direct instruction that results in the maximum amount of “truthful” content so that when confronted with misleading or outright lies on their own, a student can pause and begin the crucial process of critically thinking when they ask themselves “That’s not what I learned in school.” In an ever increasing complex world where anti-science narratives are spun, high production value “snippits” of information are easily created and social media algorithms that produce “echo-chambers” or “filter bubbles” abound, the intent of using public schools to produce knowledgeable citizens is, in my opinion, being threatened with simplistic arguments that students need not know things that can be “Googled”.

Opportunities have always, and will continue to exist to allow students choices and projects of interest in public schools, but those personal choice inquiries must be short, limited in scope, come from vetted sources (Richardson, 2012) and most importantly, must come at the end of comprehensive learning. Bloom’s pyramid of learning cannot be an inverted pyramid.

Bibliography

Dahl, Ronald E. “Adolescent brain development: a period of vulnerabilities and opportunities. Keynote address.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1021.1 (2004): 1-22.

Friesen, Norm, and Shannon Lowe. “The questionable promise of social media for education: Connective learning and the commercial imperative.” Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 28.3 (2012): 183-194.

Froehlich, Thomas Joseph. “Ten Lessons for the Age of Disinformation.” Navigating Fake News, Alternative Facts, and Misinformation in a Post-Truth World. IGI Global, 2020. 36-88.

Hektner, Joel M., and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. “A longitudinal exploration of flow and intrinsic motivation in adolescents.” (1996).

Kirschner, Paul A., and Jeroen JG van Merriënboer. “Do learners really know best? Urban legends in education.” Educational psychologist 48.3 (2013): 169-183.

Kirschner, Paul A., John Sweller, and Richard E. Clark. “Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential, and inquiry-based teaching.” Educational psychologist 41.2 (2006): 75-86.

Lapointe, Marc, “The Truth About Discovery Learning” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=De6ChXRiVmw ), (2016)

Lemov, Doug, “How Knowledge Powers Reading”, Educational Leadership, (http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/feb17/vol74/num05/How-Knowledge-Powers-Reading.aspx ) (2017)

Mayer, Richard E. “Should there be a three-strikes rule against pure discovery learning?.” American psychologist 59.1 (2004): 14.

Richardson, Will (2012). Why School? How Education Must Change When Learning and Information are Everywhere [eBook edition]. Ted Conferences.

Riedling, Ann Marlow, Loretta Shake, and Cynthia Houston. Reference skills for the school librarian: Tools and tips. ABC-CLIO, 2013.

Stokke, Anna. “What to Do About Canada’s Declining Math Scores?.” CD Howe Institute Commentary 427 (2015).

Teachthought, “30 of the Most Popular Trends in Education” https://www.teachthought.com/the-future-of-learning/most-popular-trends-in-education/ Oct. 7, 2019

Youtube Links

A typical child on Piaget’s conservation tasks, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gnArvcWaH6I

Beware online “filter bubbles” | Eli Pariser, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B8ofWFx525s

Inside the mind of a master procrastinator – Tim Urban, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=arj7oStGLkU

In A Divided Country, Echo Chambers Can Reinforce Polarized Opinions | TODAY, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I98jjGlg6tU

The Science of Anti-Vaccination, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rzxr9FeZf1g

Why incompetent people think they’re amazing – David Dunning, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pOLmD_WVY-E

Another well written and thoughtful post. You have consulted, linked and cited a strong list of resources. The “Filter Bubble” Ted Talk has always been one of my favourites! I agree that we can’t just rely on our students Googling the information they need. As you state, they need a level of knowledge before they can think critically about that information. I also feel they need to be taught specific skills in order to access accurate information. I am curious to see where this learning takes you if you choose to continue on this topic for the Final Vision Project.