In a globalized age where multinational corporations and trading blocs hold more power and political clout than ever, ordinary citizens attempt to hold onto their self-determination by appealing to ultra-nationalism. How does Canada, in all senses of the word, preserve its identity or transform with the times? We live in a nation that has a very young history and a diverse racial composition thanks to its open immigration policy, and for these reasons Canada’s self-image of nationhood is much more fragile.

Because of the diverse interests of the members of our group, we felt that it would be suitable for us to come up with our own unique intervention, which is simply asking what the Canadian identity is, or perhaps leave the answer to that question open. In this intervention, we attempt to tackle the problem of pinpointing a national identity that acknowledges the country’s diversity while still remaining relevant or meaningful to its people. In other words, we need to answer what we can call Canadian without it making it exclusionary to other narratives and peoples in this country. There are 35 million living narratives in this country, and countless fictional ones still to be discovered. These are all equally valid Canadian stories, from the newly landed Canadian at the airport, to the multi-generational white Canadian with a bloodline tracing back to the first settlers, to the Aboriginal Canadian whose ancestors have dwelled in this land for millennia.

The main questions that we asked in this project are as follows:

- What is Canadian identity? Is there such a thing as a Canadian culture?

- How do we create a singular canon of literature for our nation that encompasses a multitude of languages and a multitude of cultures?

- Should Aboriginal and colonial narratives have a special status within Canadian literature?

In many ways our intervention leaves the answers to these questions open. In fact, our intervention is based on the belief that these answers are personal and subjective, and perhaps each Canadian will have a slightly different response. Evan points out that the identity he prescribes for Canada is based on its wilderness, encompassing “prairies, lakes and rainforests”, while Timothy contends that “national pride should begin with appreciating the policies in place in our law”, a vision of Canada that emerges from its political identity. The dialogue exposed the differences in the way we, and by extension all Canadians, understand the country, yet both of our interpretations and many other interpretations of nationalism are equally valid. Through this project and this class we realize the need to listen to other people’s versions of the Canadian narrative and how it fits in with their own personal narrative. More importantly, we are reminded that not everybody shares the same beliefs, yet we can and must still work together to build a more inclusive society.

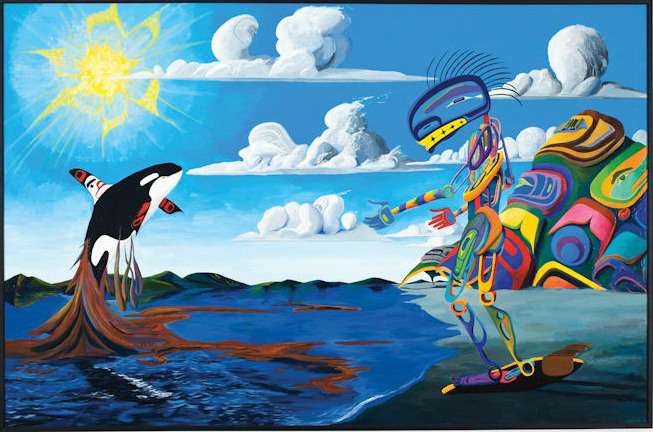

Our group was also engaged in discussing racial differences as both a dividing force through discrimination and an integrating force through multiculturalism. After reading Mukherjee’s essay, Landon realized that “Canada was a society that isolated people and treated those of minority status with injustice”. The dark underside of colonial history is often buried under the success stories and narratives of conquest over Aboriginals, and to celebrate those stories is to remind Aboriginal groups of their painful disenfranchisement at the hands of white settlers. These stories become a controversial common ground on which to build a unifying narrative for all Canadians. However, as the demographic Canada shifts towards a more pluralistic society where Caucasians no longer form the majority, we are faced with the opportunity (or challenge) to break up the hegemony of an all-white perspective. Evan directs the group to a quasi-prophetic vision of a society where “the melting pot … has overcompensated, or been subsumed in an increasingly globalized world ruled by multinational cooperation.” There is definitely some legitimacy in the anxieties expressed in the novel, and as we preside over the transition of our country we must strengthen the sense of multiculturalism or risk the capitulation of sovereignty to extra-national forces. Such a novel reminds us that a literary intervention is imperative in Canada to preserve a sense of identity built on the free expression of diversity.

Our intervention in Canadian literature begins with education.We perceive the current state of nationalism as one founded more or less exclusively on political grounds, and for many victims of political persecution this is not an inclusive common ground. We want to situate nationalism in a more intimate interpersonal realm that involves dialogue between individuals instead of interest groups against the government. In order to bring nationalism within personal experience, we want to use classrooms as an incubator of dialogue between people who would not normally have a conversation. Instilling interest in Canadian literature would be most effective with children, as they are naturally curious about their world and are more receptive to new ideas. We conceive an education curriculum where a class will have a chance to communicate online with another class that is very dissimilar to their own, so that they are exposed to another side of Canada. For example, a class from an affluent neighbourhood in Vancouver might be paired with a class in an impoverished Native reserve, and the children may share their experiences of living in Canada through online messages. We believe that this exercise will encourage children to challenge their ideas of what Canada means, as well as appreciating the similarities and differences of living in distant communities within a common nation.

We envision that the level of engagement will be structured differently for children of different age. For the young children in primary school, we believe that over the course of the seven years they will have communicated with many different classrooms in Canada. This can be done with something akin to sister cities, and have what we might call sister classrooms. The two classes may exchange emails, hold Skype conferences, share artwork created online, produce presentations to showcase their community, conduct interviews, and perhaps even collaborate on an online project together. The rapid development of technology provides opportunities in education that would not have been merely a decade ago, but classrooms have yet to embrace the full potential of these tools. A similar program called PenPal Schools has been introduced, however our intervention aims to seamlessly integrate into already existing schools and not create new ones.

Older students in high school may be challenged to take on projects that not only inspire them to seek greater personal understanding of Canadian identity, but also take action as educators within their own community. Our strategy for older youths involve pairing each student with a distant online pen pal with whom they can carry out meaningful and insightful conversations about national identity and national unity. Such projects will allow students to build personal connections and deeper understanding about another culture within Canada that bypass stereotypes in mass media and politically motivated caricatures. The insights that they develop over the course of such interactions may be meaningfully employed as students report back to the class on what they have learned. This could be done in the form of a class fair, where each student presents the experience of living in Canada through the eyes of their online pen pals. It is our hope that these educated youths might become inspiring ambassadors and cultural interpreters within their communities.

How do we plan to use these interactions in the service of Canadian literature? We strongly believe that sparking curiosity in the stories of other Canadians through real-time communication will naturally inspire young Canadians to turn to Canadian authors writing fictional and non-fictional accounts of living in this country. These online interactions may be meaningfully complemented with studying novels set in the locale where the sister class is situated. To use the aforementioned example, the class in Vancouver might read about the impacts of residential schools and the state of the reserve systems in Canada in a novel, while simultaneously supplementing that information with face-to-face interaction with children whose parents may have lived through the residential system and see the faces of children who continue to live on reserves. Conversely, the class living on the reserve may learn from the urban class about the possibility of life outside their reserves, and learn that those they perceive as colonial oppressors are not as dissimilar to themselves as perhaps portrayed by their elders or parents. In novels they might encounter characters of minority races who also face prejudice and discrimination within their urban surroundings, and perhaps identifying with these hurdles might encourage Native children to work alongside other children to combat racism. The characters that the students encounter in novels are not merely names on a page or a statistic in their history textbook; these stories they read in books are transformed into reflections of actual narratives affecting people whose faces they can see. These narratives also reveal the common challenges that transcend racial lines, but developing such awareness is most effective by nurturing conversations at the personal level.

Areas for Future Research:

1) Greater research should focus upon the merits of government-funded and school-operated programs that aim to connect students/civilians to Canada. In addition should any findings about their shortcomings be found, these should also be included.

2) What is interesting to note is that despite the fact that several guidelines for interventions against discrimination have been created, there aren’t many resources discussing their effectiveness. For this reason it is also a possible avenue for increased research.

3) Research on the effectiveness of PenPal programs in improving cultural awareness, inter-group relations, and reducing prejudice or discrimination.

4) Multicultural curriculum reform—at all grade levels—more than warrants further research. “Beyond Intellectual Insularity” is an illuminating study, but the researchers limit themselves to grades 10 and 11. This, along with the lack of multicultural literature in primary schools, suggests that pride in multiculturalism should be aroused earlier on—to inspire students to form diverse peer-groups, crave new perspectives, and accept others.