The title speaks for itself; the newly dubbed Pope Francis (previously Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio) is the first Jesuit and first Latin American in modern times to lead the 1.2 billion large Catholic population. CNN outlines ‘5 things to know about the new pope’ painting him not only as the ‘pontiff of firsts,’ from his unique name choice to his non-European background, but also as a ‘people’s pope,’ an everyman, who faces a number of challenges with regards to the deteriorated reputation of the Catholic religion in light of the ‘sex abuse by priests and claims of corruption and infighting among the church hierarchy’ in recent years.

Blog Wars?

Awaiting a topic to debate amongst you all…

Democracy and International Peace

Assessing the legitimacy of the democratic peace theory is not an examination of whether or not there exists a relationship between the dependent variable, dyadic democratic peace, and the independent variable, dyadic democratic governance. There is a long-established empirical pattern supporting the significantly lower likelihood two democracies engaging in militarized interstate disputes when compared to their autocratic or mixed dyad counterparts. Letzkian and Souva 2009 provide one such iteration of the patterns posited by democratic peace theory, by comprehensively examining data from 1946 to 2000. While the robustness of the pattern is easily discernable, whether or not this pattern is actually indicative of a correlative or causal relationship has been a matter subject to heavy scrutiny. O’Neal and Russett provide an interesting critique of the relationship between democracy and international peace.

To set the foundations for the critique of O’Neal and Russett’s “The Kantian Peace,” a definition of what exactly the “Kantian Peace” entails must first be established. Kant’s classic argument states that an international perpetual peace can exist if the following features are present: a republican constitution, a federation of interdependent republics, and a commercial spirit. Thus, Kant is not proposing a unilateral relationship with a single independent to dependent variable association; the requirements for Kantian peace necessitate the examination of at least three other independent variables. Accordingly, O’Neal and Russett aim to assess (1) democracy, (2) trade interdependence and (3) IGO involvement, in relation to peace. By performing both dyadic and systemic analyses, O’Neal and Russett ultimately conclude that Kant’s theory was remarkably prescient.

To assess the verity of O’Neal and Russett’s hypotheses, their variables and their respective measures must first be overviewed. They use a single dependent variable, DISPUTE, a dichotomous measure of whether or not there is a militarized interstate dispute (MID), and three Kantian dyadic independent variables: DEML, a gradated measure of the level of democracy in the less democratic state of each dyad, DEPENDL, a gradated measure of the level of dependence of the state less economically dependent on trade, and IGO, a gradated measure of the number of IGOs in which both states in a dyad share membership.

To best dispel the possibility of reverse causality for their purposes, O’Neal and Russett lag all independent variables from the dependent variable by one year. This precaution aims to protect again endogeneity i.e. when conflict may limit trade just as trade may constrain conflict. They also try to control for a variety of realist explanations for dyadic peace, including in their analysis the capability ratio (CAPRATIO), alliance (ALLIES), and contiguity and distance (NONCONTIG and DISTANCE). However, they do not limit the dyads examined to those that are ‘politically relevant,’ a decision which is justified as an attempt to make sure no patterns are overlooked as a result of exclusion. Ergo, in their analysis O’Neal and Russett will also give the overall dyadic results separately from ‘politically relevant’ dyadic results, and compare the two. For the years 1885- 1992, excluding the two world wars and the immediate postwar years (1915-20, 1940-46, O’Neal and Russett observed a total of 150,000 dyads.

To assess their observations, O’Neal and Russett employ a logistic regression analysis. A method of weak-link specification is applied for the DEML and DEPENDL variables, but the IGO variable is inherently dyadic. O’Neal and Russett also assess the realist control variable, to provide the following equation in summation:

(EQ1) DISPUTE= DEML + DEPENDL + IGO + ALLIES + CAPRATIO + NONCONTIG + DISTANCE + MINORPWRS

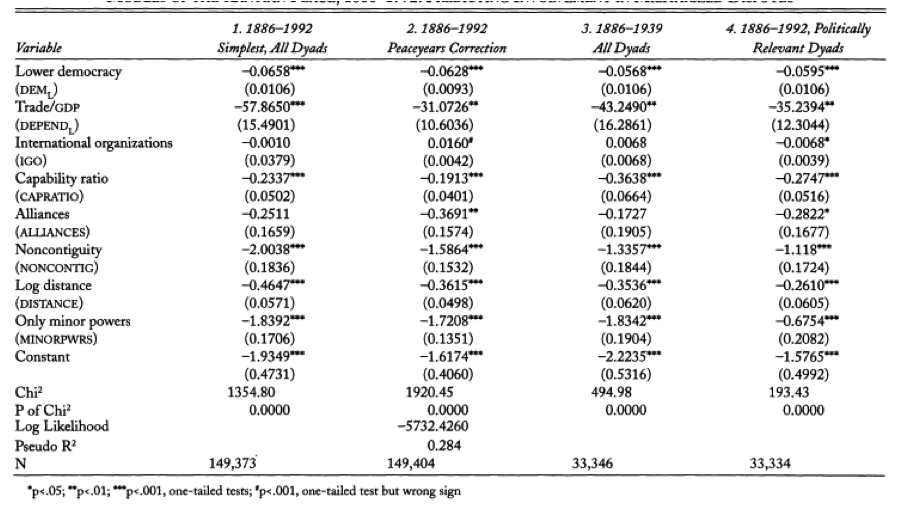

As this paper is primarily concerned with the relationship between democracy and peace, the first row of Table 1 is requires the most attention. When considering all dyads in model 1, a higher DEML is statistically significant at the .001 level, to a greater likelihood of peace. To test if this relationship exists outside of the cold war era, GEE is used again to re-estimate EQ1 for the years from 1886-1914 and 1921-39 (model 3), and the DEML remains significant at the .001 level. To investigate the possible discrepancies between including all possible pairs of states and ‘politically relevant’ dyads, EQ1 is re-estimated a third time, using only ‘politically relevant’ pairs of states, or those that contain at least one major power and those which are contiguous (model 4). Here, the positive relationship between democracy and peace remains apparent (p < .001). The results of this analysis lead to O’Neal and Russett’s conclusions that, compared with the typical dyad, the risk that a more democratic dyad will become engaged in a dispute is reduced by 36 percent, and the same risk for a more autocratic dyad is increased by 56 percent.

One of the other Kantian variables examined in O’Neal and Russett’s piece, trade interdependence (DEPENDL), takes on especial importance for the purposes of its subsequent comparison with Gartzke’s piece. The GEE estimations posit that the relationship between trade dependence and peace is equally as statistically significant (p < .001) as the relationship between democracy and peace for all dyads for all years[2], and for the pre-Cold War era, and almost as significant (p < .002) for politically relevant dyads[3]. The correlations in realist variables also play a role in the upcoming discussion of Gartzke, with O’Neal and Russett’s results corresponding to all expected patterns:

(1) A preponderance of power rather than a balance deters conflict;

(2) Contiguous states are prone to fight, as are those whose homelands are geographically proximate; and

(3) Major powers are involved in disputes more than are smaller states.

All of these realist variables are significant at the .001 level. (51)

Democracy -> International Peace?

To discuss O’Neal and Russett’s “The Kantian Peace: The Pacific Benefits of Democracy, Interdependence and International Organizations” a definition of what exactly the “Kantian Peace” entails must first be established. Kant’s classic argument states that an international perpetual peace can exist if the following features are present: a republican constitution, a federation of interdependent republics, and a commercial spirit. Thus, Kant is not proposing a unilateral relationship with a single independent to dependent variable association; the requirements for Kantian peace necessitate the examination of at least three other independent variables. Accordingly, O’Neal and Russett aim to assess (1) democracy, (2) trade interdependence and (3) IGO involvement, in relation to peace. By performing both dyadic and systemic analyses, O’Neal and Russett ultimately conclude that Kant’s theory was remarkably prescient.

In their analysis, they use a single dependent variable, DISPUTE, a dichotomous measure of whether or not there is a militarized interstate dispute (MID), and three Kantian dyadic independent variables: DEML, a gradated measure of the level of democracy in the less democratic state of each dyad, DEPENDL, a gradated measure of the level of dependence of the state less economically dependent on trade, and IGO, a gradated measure of the number of IGOs in which both states in a dyad share membership.

To best dispel the possibility of reverse causality for their purposes, O’Neal and Russett lag all independent variables from the dependent variable by one year. This precaution aims to protect again endogeneity i.e. when conflict may limit trade just as trade may constrain conflict. They also try to control for a variety of realist explanations for dyadic peace, including in their analysis the capability ratio (CAPRATIO), alliance (ALLIES), and contiguity and distance (NONCONTIG and DISTANCE). For the years 1885- 1992, excluding the two world wars and the immediate postwar years (1915-20, 1940-46, O’Neal and Russett observed a total of 150,000 dyads.

To assess their observations, O’Neal and Russett employ a logistic regression analysis on the following equation:

(EQ1) DISPUTE= DEML + DEPENDL + IGO + ALLIES + CAPRATIO + NONCONTIG + DISTANCE + MINORPWRS

Table 1 in the paper summarizes the results attained from their analysis; the results that I find most compelling are found in the first row. The association between democracy and dyadic peace is signifiant at the p<.0001 level.

R.I.P. Chavez

Chavez’s death leaves Venezuela in a critical state; the response in Washington was quick and almost too eager. According to CNN, the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Sen. Robert Menendez views Chavez’s death as having “left a political void that we hope will be filled peacefully and through a constitutional and democratic process, grounded in the Venezuelan constitution and adhering to the Inter-American Democratic Charter.” Basically, he is hoping for Venezuela to return to its ‘once robust’ system of democracy’ by calling for free and fair elections to occur in the aftermaths of the dictator’s death. This is a sentiment shared by many, including Venezuelan citizens and expats, not just U.S. politicians. However, there appears to be an equal number of mourners among the celebrators; despite any disagreements with his leadership style, Chavez was truly committed to improving the lives of his fellow countrymen, with a particular focus on the poor and the disenfranchised. In his time in office, it is estimated that he has cut the country’s poverty rates in half.

These mixed reactions to Chavez’s death, whereby some are critical of his presidency, saying it was “characterized by a dramatic concentration of power and open disregard for basic human rights guarantees” (Human Rights Watch), and others are mournful of a man who was a ‘champion of the poor’ bring to light questions about the inherent value we seem to attribute to democracy. This is obviously something that has been discussed, and rehashed repeatedly in class; I think there is a general consensus that authoritarian regimes demonstrate greater efficacy and effectiveness in enacting any substantial changes. This makes sense because power is concentrated in one, a select group of, person/s, as opposed to the diluted, separation of powers democratic approach. Evidently there is the incentive to abuse power when it is left unchecked, but, in the cases of those like Chavez, who, according to some at least, had truly noble intentions, perhaps there really is some merit to the idea of the ‘gentle, benevolent dictator.’ What do you think? Should the people be excitedly calling for ‘democracy, democracy, democracy’ to be reinstated in Venezuela?

Harlem Shake: Arab style

I am sure many of you have (unfortunately) been exposed to the proliferation of “Harlem Shake” videos out there. In fact, UBC students created our very own “Harlem Shake” video less than a month ago. While most of these bizarre group videos are nothing more than a source of amusement, laughter and incredulity, the Harlem shaking that’s going on in the Arab world is causing concern among its leaders as a “potent symbol of protest, revolt and defiance” (Jason Miks, “Harlem Shaking the Arab World?” Global Public Square, CNN).

The videos appearing in Tunisia and Egypt are not recognizably different from those which we see being produced all over the place in North America (note the 20 or so different iterations of “UBC Harlem Shake” on YouTube), the corresponding government responses, and respective backlashes have made them into a video protest of sorts. The authorities’ initial responses to the first Harlem Shake videos in Tunisia and Egypt set off big reactions and prompted backlashes that have gone viral online. Miks seems to think that this is a demonstration of the value of American cultural exports, but I don’t think that a particularly profound message is being spread when shirtless men perform pelvic thrusts. What do you think? Is Harlem shaking indeed shaking up the Arab world?

Bloggical Fallacies

The logical fallacies I chose to explore are ‘arguments from authority’ (also known as ‘appeals to authority’).

The basic structure of such arguments is as follows: Professor X believes A, Professor X speaks from authority, therefore A is true. Often this argument is implied by emphasizing the many years of experience, or the formal degrees held by the individual making a specific claim. The converse of this argument is sometimes used, that someone does not possess authority, and therefore their claims must be false. (This may also be considered an ad-hominen logical fallacy – see below.)In practice this can be a complex logical fallacy to deal with. It is legitimate to consider the training and experience of an individual when examining their assessment of a particular claim. Also, a consensus of scientific opinion does carry some legitimate authority. But it is still possible for highly educated individuals, and a broad consensus to be wrong – speaking from authority does not make a claim true.This logical fallacy crops up in more subtle ways also. For example, UFO proponents have argued that UFO sightings by airline pilots should be given special weight because pilots are trained observers, are reliable characters, and are trained not to panic in emergencies. In essence, they are arguing that we should trust the pilot’s authority as an eye witness.There are many subtypes of the argument from authority, essentially referring to the implied source of authority. A common example is the argument ad populum – a belief must be true because it is popular, essentially assuming the authority of the masses. Another example is the argument from antiquity – a belief has been around for a long time and therefore must be true.

The above description is taken from:

Bloggical examples of this logical fallacy?

My own! I often quote arguments from lectures made by various profs (i.e. here, here, and here).

Democracy and Economic Growth

It is clear from the readings this week that there is an empirically observable relationship between democracy and economic growth. What remains unclear is whether or not this relationship is a causal one. Gerring et al’s piece attempts to establish a number of causal mechanisms linking democracy to economic growth, with the important scope condition of time. The following figure, taken from their article, outlines the main causal mechanisms identified:

The discussion they present of democracies’ creation of physical, human, and social capital do not introduce any new or original ideas. In their discussion of political capital, however, the time factor becomes a subject of emphasis. Democratic political arrangements create a number of political outputs that are assumed to have a direct impact on economic performance, i.e. “market-augmenting economic policies, political stability (understood as a reduction of uncertainty), rule of law, and efficient public bureaucracies.” Valuations of these aspects of political capital are dependent on regime length, which Gerring et al. describes as a. ‘learning’ and b. ‘institutionalization’ processes. In sum, Gerring et al. conclude that, if maintained over time, democracy influences economic performance through four main channels – physical, human, social and political capital- constituting a ‘democratic growth effect.

‘Africa’s rocky road to democracy’

Came across a story on CNN that is very relevant to the aims of this seminar. Mbaku gives an overview of the tumultuous road Africa has been on in the past two decades in their transition to democratic governance, which has resulted in successful overthrows of authoritarian regimes, but some major reversals as well. His overview is largely a positive one; despite briefly remunerating the instances where transitions have not been successful and setbacks have occurred, Mbaku is much more focused on the “significant and spectacular achievements in the continent’s struggle to deepen and institutionalize democracy.”

What I find most memorable about his piece are his evaluation of and prescriptions for the Arab Spring countries, most specifically Libya, Tunisia, and Egypt. He views the problems there as “symptomatic of what needs to be done throughout Africa to deepen and institutionalize democracy.” The only real solution, he says, is to engage each stakeholder group in the nation (i.e. Morsy and his Freedom and Justice Party in Egypt) to work together in a democratic fashion to create a system wherein all population groups can coexist peacefully. How is this supposed to be carried out? That he is not so clear about. Mbaku’s solution is oversimplified, and, altogether, too optimistic. What he fails to recognize is the possibility that the traditional (Western) approach to democracy may be inapplicable in the case of the Arab Spring; fixing the problems there now would require measures that extend far beyond peace talks he envisages.

Where are all the billionaires?

According to this article by CNN, of the world’s 1453 billionaires, about half reside in the U.S. or China, but the single city with the highest number of billionaire residents is Moscow at 70. And just in case you’re interested in the fascinating world of the obscenely wealthy, here’s a list of the 10 richest billionaires (quite literally the richest of the rich):

1. Carlos Slim Helu & family (Mexico – America Movil) : $66 billion

2. Warren Buffett (U.S. – Berkshire Hathaway): $58 billion

3. Amancio Ortega (Spain – Zara): $55 billion

4. Bill Gates (U.S. – Microsoft): $54 billion

5. Bernard Arnault (France – LVMH): $51 billion

6. Larry Ellison (U.S. – Oracle): $43 billion

7. Li Ka-shing (Hong Kong – Cheung Kong): $32 billion

8. Charles Koch (U.S. – Koch Industries): $31 billion

8. David Koch (U.S. – Koch Industries): $31 billion

10. Liliane Bettencourt (France – L’Oreal): $30 billion