In Safe Area Gorazde, with the style of graphic narration, aiming to depict the real image of Bosnia war from 1992 to 1995, Joe Sacco introduces people a relatively new perspective of viewing the war and the victimhood. According to Tami Amanda, an academic scholar in the University of Manitoba, puts forward with a theory of victimhood identity; he argues that the victimhood constitutes with five stages: structural conduciveness, political consciousness, ideological concurrence, political mobilization and political recognition (Jacoby, Tami A., 2015). The five sequential stages mainly introduce that a victim-based identity or victimhood is both socially and politically structured and it needs the proper political culture and power to express itself. In other words, the social context matters for the definition of victimhood. Mariano Lima, the president of a Peruvian victim-survivor association (VSA), echoes Tami Amanda’s idea with his concept of “external victimhood”, one of the “two-model” of victimhood which also includes an “internal one”. (Waardt, Mijke De, 2016). The former refers to the objective definition provided by social institutions, while the latter self-definition of victimhood. Joe Sacco, however, not only affirms the internal definition of victimhood (which I’ll argue in my paper rather than here) in Safe Area Gorazde but also invents a relatively new one (my argument here) that can be achieved by another angle of the “external victimhood”, that is, from the readers’ perspective, rather than completely relying on the social context or institutions, to define the victimhood, and this new way of definition will be the basis of my further analysis of the rationality behind silly girls’ behaviour.

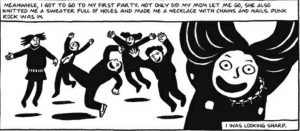

One of the merits of Joe Sacco’s graphic narration is that the characters are real, so do their lives. People living under threat of war, generally, seem to be unconsciously divided from people living in peace, as generally, it takes for granted for the latter to seek for and enjoy material life. In other words, in some precarious situations, the former, are totally excluded from owning the “normal desires” such as pursuing the materials as they are usually perceived to do what they should do rather than what they want to do. Where does the line diving the two groups come from, or “victims” living in danger naturally don’t have the right to own and enjoy the same stuff as onlookers who live in peace? On page 50, with the title named as Silly Girls, Joe depicted the scene in which he and Edin were enjoying a gathering with some girls. These young girls, without any access to education because of the war, as Joe called them, were the most “giggly hostesses” in the town, energetically sharing their personal stories and laughing with their guests. Then on page 56, when Joe implied that he would leave for Sarajevo and asked if there’s anything these girls want, on the second panel of the first tier, “JEANS!” amazingly appears in the bubble, placed above a couple of girls’ exciting expressions, and the next frame continues their “specific requirements of the jeans”. However, after Edin suggested preparing the money for their future education, the girls became silent and Joe concluded that: “they were a couple of silly girls”. What makes this section sad is that on one hand, saving the money for education is wise, but on the other hand, can anyone tags the girls as “silly” just because they spent the money purchasing what they want as normal young girls? I would like to argue that these girls’ “silly desires” are, in fact, natural and reasonable and should not be blamed at all; there’s nothing that can make such an exclusion, which, to some extent, devalues some people’s lives just because of their living conditions which they have no choice to resist. Girls are girls: money can be prepared for the better purpose, but it doesn’t mean that it’s irrational and silly to buy something satisfactory.

Furthermore, their so-called silly behaviors lead me to a deeper thinking: why the idea of future education didn’t come to mind when they were asked what they want? Were they really too silly to think about their education? Maybe not. I presume that the reason why these girls were crazy about materials was that they were pushed quite far away from their “spiritual needs”; in other words, they were suffered from a loss of hope. The war was so cruel that it not only deprives people’s basic needs but also indirectly sent people a message that the future may be as struggling as the presence. For these girls who were not capable of escaping from the war zone, what else could they seek for? What types of hope were rational for them to pursue? Hence, the “silly girls” were placed in an opposite position from the war, that is, they were victims, and that’s where Joe Sacco’s novel definition of victimhood comes from.

Briefly, through the deep analysis of those girls’ craziness about American-made Levi’s jeans can lead to more information than a simple tag “silly girls”. The cruel side of war “squeezed out” people’s hope and their planning for future, so it’s quite reasonable for people living in precariousness to ask for what may satisfy their material needs rather than an incredibly distant spiritual goods. Therefore, in most chapters of Safe Area Gorazde, the victim-based identity belongs to neither an absolutely subjective nor an “external one”; rather, Joe’s creative definition comes from a relatively external perception or, as we can say, the public’s perspective, to examine the internal lives and desires, and the “social criticism” can, on the other hand, help confirm the victimhood comprehensively.

Thanks for reading 🙂

References

Jacoby, Tami A. “A Theory of Victimhood: Politics, Conflict and the Construction of Victim-Based Identity.” Millennium – Journal of International Studies, vol. 43, no. 2, 2015, pp. 511-530doi:10.1177/0305829814550258.

Waardt, Mijke De. “Naming and Shaming Victims: The Semantics of Victimhood.” International Journal of Transitional Justice 10.3 (2016): 432-50. Web.

Recent Comments