Reggio inspired teachers view their students as protagonists. They view students as the main characters of their learning who are active in their experiences at school. The image of the child is one of respect and admiration. Children are viewed as powerful, naturally curious and creative.

Some believe that traditional schooling and perspectives underestimate children and “underestimate the depth of children’s thinking” (Fraser, 2012). This is not the case in the Reggio approach.

“…We in the Reggio Emilia view children as active, competent, strong and finding meaning. Not as predetermined, fragile, needy and incapable.” (Innovations, 2001)

Childhood in itself is viewed positively, rather than as a temporary state requiring remediation or “fixing”. Unlike in the Montessori approach, children are not treated as “little adults”. All the languages of children are treated with respect- including imagination, pretend and drama.

I have been challenging my own views of the image of the child, and this has proven to be an ongoing process.

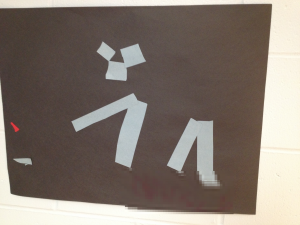

This picture is from a lesson I did with a group of four and five year old children. I thought I had designed an excellent early literacy lesson. I read a book with a high amount of print exposure and repetition of the word “WOW”. I then showed students on a chalkboard how I could use four lines to make the letter “W”. I followed this up with an activity. I gave students strips of paper as a provocation to see if they might be able to make a letter. Some students did make letters including the predictable W, and even some first initials like the letter “A”.

I kneeled down beside once child and asked “And which letter is this?” I thought she had made an attempt at the letter “V”. She looked back at me with an incredulous look on her face. Perfectly calmly she said “It’s Pants”.

I looked again. They were in fact pants.

I realized my activity was less open ended than I had believed. My direction and interpretation of the scenario was entirely teacher driven. In my mind I had limited the acceptable languages to only cognitive-linguistic representations.

The art the student had produced was highly novel, creative, and symbolic. Although it was not the outcome I had expected, it was noteworthy in it’s own right. In an early childhood context, I was simply happy to witness the joy and creativity in her expression.

I wonder if I would have felt the same about an unexpected outcome in an intermediate context where there is more pressure regarding curriculum outcomes and assessment. I wonder about what other types of evidence of learning I could accept. Honouring the 100 languages of children would mean expanding my ideas and opening my mind up to alternative ways of showing understanding. I will keep reflecting on my own image of the child as I continue to be inspired by the Reggio approach. I will also be challenging myself to document and make children’s thinking visible in order to see one hundred languages in the intermediate years.

Innovations in early Education: The International Reggio Exchange. Detroit: The Merrill-Palmer Institute, Wayne State University.