The Mad Rush to Tokyo: The Private Sector Role in Urban Population Control

Despite its declining and aging population, Tokyo, the capital city of Japan still sustains a high position in the ranks when it comes to urban population. Wendell Cox highlights the new publication of Demographia World Urban Areas in which the “Tokyo-Yokohama continues its 60 year leads the world’s largest urban area” .

Factors that contribute to the increase in population in Tokyo, despite the overall decrease in the population of the country, is attributed to the disproportionate population concentration to the capital city relative to the decline in population in the rural town areas. One of the reasons behind this trend is outlined by Career Connec. News, in which the unnamed author highlights the lack of job opportunity outside of the central cities. The author indicates the vicious cycle in which as young people flee their rural town homes to the city centres because of the lack of employment opportunity, this decrease in population causes the region to be unattractive to businesses to consider any investment in these regions, and thereon persisting the the issue of lack of job opportunity.

Under these situations, as a human geographer, what drives my curiosity is how has the city adapted to these forces, and how has the government responded to these conditions. In reflection of Yasushi Ysubomatsu’s article on the poor delivery of the “Communities, Sages, and Jobs Rebirth Act” for rural revitalization as proclaimed by Prime Minister Abe Shinzo in 2014, I consider the private sector response to create new vibrant, massive, urban shopping districts to reduce these pressures and concerns by the population. While these new developments help as design strategies around this issue of overpopulation, I argue that it follows the typical Japanese ‘coping’ strategy to adapt and work around the conflict, rather than to solve it from it’s root cause.

In 2014, in recognition of the trends of the decreasing Japanese population rate, Prime Minister Abe Shinzo promised action in the name of “Communities, Sages, and Job Rebirth Act“. This agreement was to invest in regional planning of the countryside, where the population is expected to drop significantly, based on the estimation by the Japanese Population Bureau that “half of the Japanese municipalities would be abolished by 2040” (Tsubomatsu, p.267, 2016). Yet this data from the World Bank Data reveals that this effort has not been yet achieved as the population of rural Japan between 2010 and 2016 is in rapid decline.

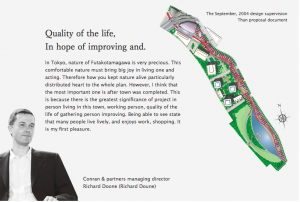

In contrary to the revitalization of rural areas of Japan, the central core of Tokyo is seeing a trend of rapid development in many of its 23 wards. At an alarming rate, rapid development by privately owned developers are creating vibrant urban cores. In this quick, informal list of the developments planned to be completed by 2016 and by 2020, this page introduces 19 new facilities being built. (Consider this scale in the context of Vancouver–it is approximately the equivalent of a Pacific Centre being built in 19 different neighbourhoods!). Some of these facilities are high tower buildings, but some are large scale projects that require careful integration with subway stations such the project that is being planned at around Shinagawa and Tamachi Station. Shopping districts such as the Futako Tamagawa Rise site is the product of a newly revitalized town, in which attracts young families to live in the Futakotamagawa Rise Residences, and find family services within the Futagotamagawa Rise Plaza Mall.

What I observe in this trend is how the private sector has taken the concerns of over-population in the city under their own market. They have noticed the concerns about limited space in the city, and with the stamina of the private sector, they have created new modern spaces in the metropolis which are designed to mitigate the congestion. For instance, the

design of the Futako Tamagawa Rise emphasizes it’s integration of nature in an urban environment. However, while these developments are possible solutions to divert the sprawl of the city outwards and instead upwards into the sky, it doesn’t change the absolute number of the population, which is creating the stress on the available land.

I believe this trend reflects a Japanese style of coping with societal issues in which, they find ways to adapt and live with the problem, rather than disrupting the common narrative to resolve the root cause. Such societal issues that follow this pattern include the divination of rooms for smokers and non-smokers, and gender-separated railway cars as a solution to the groping issues Japanese women face in their daily commute. Instead of creating greater awareness and changing attitudes around the issues, Japanese strategies tend to avoid creating any interruption to the daily routines, and instead consider solutions to work around the issue.

Based on the estimate by the Population Bureau, the projection that claims that 50% of Japan’s towns are under the threat of extinction, this is a severe problem for the Japanese society. Rural societies are still critical regions to feed the urban core, as well as serving as buffers to the over populated central city core. Yet, as a creative and innovative nation, I believe there is potential for Japanese entrepreneurs to make rural towns attractive, and slowly re-direct young people and businesses back to the land of everyone’s family roots and origins.