Conceptualization of Democracy

For the purpose of assessing the measures of democracy for the Southeast Asian countries (which include Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam), this report conceptualizes democracy according to two components of democracy, namely competitions and majority rule. As such, a country will be categorized as democratic if its governing body makes decisions based on the voting of more than half of the eligible and present voters, regardless of whether that majority is derived from an electorate, a parliament, a city council, a party caucus, or a committee”.[1] In terms of competition, the practices of election are used to attest the countries’ democratic practices.

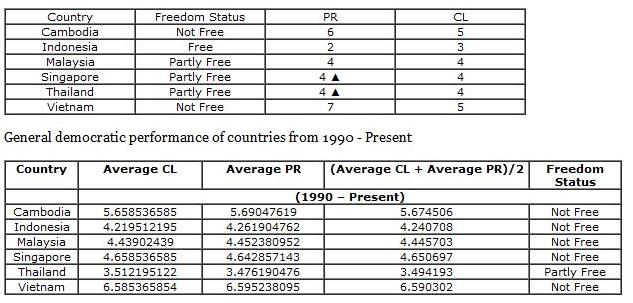

Using the datasets of the Freedom House (FH) and the Political Regime Change (PRC), the report compares the two measures’ findings on the democratic performance of the countries during the period from 1990 to the present.

Summary of Major Measures

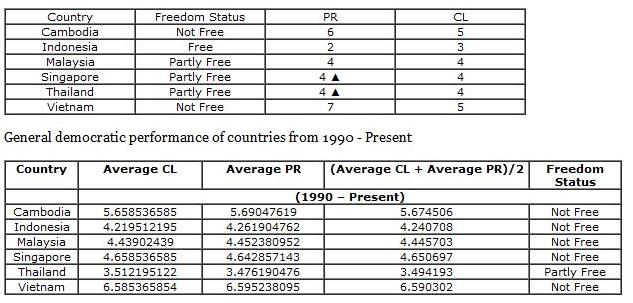

1.) Freedom House Dataset (2012)[2]

How a regime is categorized (also used in data analysis):[4]

NOTE: The ratings reflect global events from January 1, 2011, through December 31, 2011.* ▲ ▼ up or down indicates an improvement or decline in ratings or status since the last survey.*”PR” stands for “Political Rights,” “CL” stands for “Civil Liberties,” and “Status” is the Freedom Status.

*************************************

To begin, Freedom House (FH) measures whether a country is a democracy or not by rating not the performance of the respective governments, but the degree of political rights and civil liberties enjoyed by its citizens (/residents). Then, political and civil rights are measured on a 1-7scale (with lower scores representing greater freedom); the average scores on both scales are then used by FH to classify countries into one of three categories, namely Free, Partly Free, and Not Free.[3]

Average score between 1 and 2.5 = ‘Free’ = Democratic

Average score between 3 and 4 = ‘Partly Free’ = Semi-democratic

Average score greater than 4 = ‘Not Free’ = Authoritarian

2.) Political Regime Change Dataset

East and Southeast Asia (from 1953- 1998)

Cambodia: A, 11/1953–9/1955; S, 9/1955–9/1957; A, 9/1957–9/1993, S, 9/1993–12/1998.

Indonesia: D, 12/1949–3/1957; A, 3/1957–12/1998.

Malaysia: D, 8/1957–5/1969; A, 5/1969–2/1971; S, 2/1971–12/1998.

Singapore: S, 8/1965–12/1998.

Thailand: A, 1932–5/1946; S, 5/1946–11/1947; A, 11/1947–10/1973; T, 10/1973–2/1975; D, 2/1975–10/1976; A,10/1976–7/1986; S, 7/1986–2/1991; A, 2/1991–9/1992; D, 9/1992–12/1998. Vietnam, Republic of: A, 6/1954–4/1975.

Vietnam, Socialist Republic of: A, 6/1954–12/1998.

(……….)

Comparison between Measures

It is found that the annual coding of FH and PRC (during 1953- 1998) are highly correlated, as reflected by the high “rank correlation coefficient of 0.83 between the PRC regime value and the Freedom House average score”. Because of the inclusion of an intermediate category, “Partly Free”, in the FH data, PRC share more concordance with FH than with other datasets.[5] Similarly, for both PRC and FH datasets, values of 1, 2, and 3 were assigned, respectively, to authoritarian (Not Free), semi-democratic (Partly Free), and democratic (Free) regimes.[6]

(……….)

Assessment of the Usefulness of the Measures

The problem of the FH measures is that it does not offer a categorical measure for democracy. It follows that, others researches that use different criteria to measure democracy would find the FH dataset ambiguous.[7] For example, it is debatable whether a country with an average score of 2.5 or less in the FH dataset should be categorized as democratic, given such country often scores 3 out of 7 on the civil liberties scale, [8] suggesting the lack of citizenship rights in the country. The shortcoming of the FH measures suggests the need for more intermediate categories (besides simply “Partly Free” in the FH case) in regime datasets. As such, the PRC dataset should be used to complement that of the FH, meanwhile to provide a measure compatible with the conceptualization of democracy in this report.

The merit of the PRC dataset is that its focus on election allows for “intercoder reliability”; accordingly, other researchers would be more able to classify observations in a coherent manner as the PRC because of the nature of elections (easily observable as they either present or absent). [9] On the other hand, although the reliability of a measure can be ensured by focusing on elections, it is pursued at the expense of validity, because in many contemporary regimes, authoritarian and democratic elements often co-exist. [10]

[1] Schmitter, Philippe C., and Terry Lynn Karl, “What Democracy Is… and Is Not,” Journal of Democracy 2, no. 3 (1991): 75-88.

[2] Freedom in the World 2012: The Arab Uprisings and Their Global Repercussions, report (2012), 16- 21.

picture from The Guardian

picture from The Guardian