Red bean mocha bubble waffle is too sweet.

The looking away | www.mandychen.me

Red bean mocha bubble waffle is too sweet.

Photos first!

Last three photos were taken @Stanley Park.

The light was not good for photo-taking. Tried my best.

And happened to see this when browsing this post from my phone.

Good night.

* Title from George Orwell’s 1984 by the character named O’Brien.

* SPOILER ALERT *

I still remember back in high school, I once argued with one of my classmates whether Winston, the hero of the book 1984, dies or not when the story ends. My friend and I stood on the side that Winston does not die, otherwise the story would lost its sense of irony. But my classmate, who just finished reading 1984 at that time, insisted on Winston’s death at the end.

“Well that’s find out then.” I said, and went looking for the ebook online. It turned out that Winston died, on the last page of the book.

What? How? Why?

It haunted me for some time, because I couldn’t understand the purpose of his dying in the end. If he went on living he would just live in torture. Isn’t that better, in the sense of leaving the readers with a more painful ending? But after reading this book for the second time, I started to see why Orwell designed the ending to be like this.

If we take a look at how Winston, after being caught and prisoned in the Ministry of Love (the name is such a big irony), went through the three-stage transformation (or cleaning/reintegration): learning, understanding and acceptance, we would know the purpose of this time-consuming and effort-taking reintegration: to change him completely. The ideal result is not Winston confessing whatever is thrown to him, but feeling his own mistakes from the bottom of his heart. That is, changing him into a different person by emptying his mind and soul, and then filling him with things they want, the Big Brother wants, and the Party wants.

One of the ironies (this book is full of ironies, of course) that really puts a bitter smile upon my face is what O’Brien, an extremely intelligent lunatic (in the eye of Winston), said to Winston: “We shall meet in the place where there is no darkness.” I knew, because I read this book before, that it can’t mean something positive and nice and shiny. It turns out the place with no darkness is the prison. But I remember the first time of my reading. I totally held some kind of unrealistic illusion towards the whole thing. It is made very clear by Orwell that the relationship between Winston and Julia and their betrayal to the Party can never last long. Winston has always considered him to be dead, and from the moment he wrote down “Down with Big Brother”, he knew he would be arrested by the Thought Police one day, sooner or later. But here’s the art of telling readers everything straightly – it makes them think what later happens must be different from what you have told them already. Now that I read it again, I can see how the ending lies plainly in the text.

How Orwell describes the whole intention of seizing power, controlling minds and turning thought criminals to be totally different persons, I would say, is amazingly horrifying. I didn’t take notes when reading the book, but here’s a part that I quoted from O’Brien:

“Power is in inflicting pain and humiliation. Power is in tearing human minds to pieces and putting them together again in new shapes of your own choosing. Do you begin to see, then, what kind of world we are creating? It is the exact opposite of the stupid hedonistic Utopias that the old reformers imagined. A world of fear and treachery and torment, a world of trampling and being trampled upon, a world which will grow not less but more merciless as it refines itself. Progress in our world will be progress toward more pain. The old civilizations claimed that they were founded on love and justice. Ours is founded upon hatred. In our world there will be no emotions except fear, rage, triumph, and self-abasement. Everything else we shall destroy—everything. Already we are breaking down the habits of thought which have survived from before the Revolution. We have cut the links between child and parents, and between man and man, and between man and woman. No one dares trust a wife or a child or a friend any longer. But in the future there will be no wives and no friends. Children will be taken from their mothers at birth, as one takes eggs from a hen. The sex instinct will be eradicated. Procreation will be an annual formality like the renewal of a ration card. We shall abolish the orgasm. Our neurologists are at work upon it now. There will be no loyalty, except loyalty toward the Party. There will be no love, except the love of Big Brother. There will be no laughter, except the laugh of triumph over a defeated enemy. There will be no art, no literature, no science. When we are omnipotent we shall have no more need of science. There will be no distinction between beauty and ugliness. There will be no curiosity, no employment of the process of life. All completing pleasures will be destroyed. But always—do not forget this, Winston—always there will be the intoxication of power, constantly increasing and will be the trill of victory, the sensation of trampling on an enemy who is helpless. If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face—forever.”

Forever.

For the world of 1984, cheers.

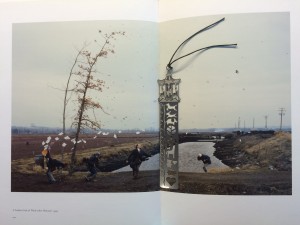

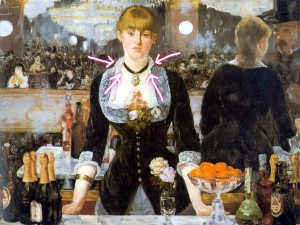

Édouard Manet, Un Bar aux Folies Bergère (A Bar at the Folies Bergère), oil on canvas, 96 × 130 cm, 1981-82, Courtauld Gallery, London.

Found a choker (or *doggy collar*) in this piece of artwork:)

This essay is both interesting and deep. It starts with a very easy to read anecdote, details are very vivid: “always together, speaking Spanish”, “mysterious books”, “wrapped in brown shopping-bag paper” (this one appeared again later) and “closed firmly behind them”. Naturally I had the feeling when I finished the first paragraph: tell me more! Why do these details sound so mysterious? Also these words are those kind of details that a child would notice. I was attracted by this essay right away.

Later the author went to elementary school. On the first day, he saw his mother’s face “dissolve in a watery blur behind the pebbled-glass door”. After I read the whole essay and went back, I quickly realized that later, a similar scene with different emotions attached appeared. Finally after the anecdote, family background comes in. “A few neighbors would smile and wave at us. We waved back.” A short sentence creates a sense of silence. “Conveyed through those sounds was the pleasing, smoothing, consoling reminder that one was at home.” Adjectives in a row strengthen the feeling. “At six years of age, I knew just enough words for my mother to trust me on errands to stores one block away – but no more.” The “just” and “but no more” are used really good. The author talks about how he was a listening child. True. I can understand the feeling of being a sensitive kid. The author can even notice this kind of detail as a child as how “listeners would usually lower their heads to hear better what I was trying to say” (the detail reappeared later), and how the sound in their house changed when the door opened because English came in. He and his brothers and sisters were isolated to be outsiders of the American society because they could not speak fluent English. The author, thus, found the difference between public sound and private sound. Furthermore, public individuality and private individuality. The description of the classroom memory is really impressive: “‘Richard, stand up. Don’t look at the floor. Speak up. Speak to the entire class, not just to me!’ But I couldn’t believe English could be my language to use. (In part, i did not want to believe it.) I continued to mumble. I resisted the teacher’s demand. (Did I somehow suspect that once I learned this public language my family life would be changed?) Silent, waiting for the bell to sound, I remained dazed, different, afraid.” Like before, here three adjectives are used in a row. Language, or rather, sound and the author’s childhood memory are closely linked together in his mind.

From his own experiences and feelings, he disagrees with bilingual supporters’ opinion that the family language can help achieve his individuality. Contrarily, he felt the separateness more strongly. These bilingual educators also hold the point that their home gives them individuality. But he does not think so. He argues there are two types of individuality. One is public, one is intimate (private). Individuality can only be achieved through achieving public individuality. It is a very interesting point. However, later in this essay he says that after he could finally speak fluent English, strangely, he couldn’t speak Spanish fluently. And then he was mocked by his family members. And in some way, he lost his private individuality. Does he really agree with himself? It seems that the inability to speak fluent Spanish made him suffered. And maybe, he felt bad about achieving the so-called public individuality. As he says in the essay: “For my part, I felt that by learning English I had somehow committed a sin of betrayal…Rather, I felt I had betrayed my immediate family.” Maybe that’s why the tone is strong (at least to me) when arguing about public individuality. It reminds me of how one would try to prove something or persuade others particularly when they actually have doubts about it and are trying to make themselves believe it too. It looks like some kind of compensation to the author to think that public individuality is the most important and without which he couldn’t have achieved individuality, so that he wouldn’t feel so bad about losing private individuality to some extend.

Interestingly, some repetitions occurred. The schoolbooks covered with brown shopping-bag paper and people lowering their heads to listen to the author speaking Spanish (instead of English). Later he had the new discovery: the intimacy is not created by language itself, but the intimates. “I would dishonor our intimacy by holding on to a particular language an calling it my family language. Intimacy cannot be trapped within words; it passes through words. It passes. Intimacy leave the room. Door closed. Faces move away from the window. Time passes, and voices recede into the dark. Death finally quiets the voice. There is no way to deny it, no way to stand in the crowd claiming to utter ones’ family language.” It makes me think of how some international students become especially patriotic after they go abroad. They post how they miss home and wish they can go back. But why? Maybe they map their feelings towards their dear friends, family or even food onto their home country. Isn’t it strange? What they love is actually just memory. At the end of this essay, the author, when looking at the photo of his dear grandmother in her funeral, did not see the familiar face, but a “public” face, the face she had when “the clerk at Safeway asked her some question and I would need to respond”.

Aye, that’s what he means by “death finally quiets the voice”.