Fish in Japan is a rather particular nature. Fish is an essential part of Japanese daily life. A strong demand for fish is particularly pronounced in Japan. The fish in national diet is a good example, (Carl-Christian Schmidt, 2003) Per capita supplies of fish and fish product in Japan is estimated at 70.6 kg per year compared to a world average of 15.0 kg. Correspondingly, Japan has really huge fish catch for supporting domestic consumption. Japan harvested a total of 6.25 million tons of fish to a total value around 11 billion USD, which made Japan the second largest producer in the world. Interestingly, Japan’s fisheries production doesn’t continuingly increase with the (FAO) growing human consumption. In 2009, Japan’s fisheries production volume was 5.43 million tons, which is about half the peak volume in 1984. Not only Japan, but every fish production and consumption countries in the world face the dilemma: How to ensure both the sustainability of fish resources and stability of fish supply? Probably, I can’t give the answer in this blog. But it is quite worthy of studying the fish catch policy in Japan which is well-known for its coastal community based fisheries management and its approachs to sustain fish resource.

Fish catching management methods in Japan

In the White Paper of fishing in Japan, it states three resource management methods to protect fish from overexploiting in Japan: input control, technical control and output control.

The input control is the fishery permission system which controls the quality and quantity of fisheries operation, i.e. restrict the number of vessels, the engine power of vessels and operating periods, etc. The technical control regulates the ways of operation, such as, the maximum net mesh size, the banning on spawning period and establishment of protective zones. In the language of what we learnt in 525, these two methods could be understood as controlling of “effort”. The fishery permission system and operation regulations raised the cost of efforts of fishing, so that curb the excessive inputs of overfishing. However, as fishing is open access resource, it will definitely be profitable in the terms of no COGS (Cost of goods sold) but expenses (“effort”), fish catchers have enough incentives to pursue profit as they only pay for expense. Even, under technical control, the technical development in fishing would offset the effectiveness of policy. Hereby, output control is quite important and Japan executes Total allowable catch (TAC).

The TAC system directly manages the catch of specified species with the upper limit of total catch in tonnage. Currently, TAC apply to eight species. Research ship surveys of the seas are conducted every year to assess the status of fish stocks. Fisheries Research Agency makes recommendations on the total catch amount based on the stock assessment and socio-economic conditions of the fishery type. This method is actually the disaggregated quota that we learnt. It helps to retain the fish resource and solve dumping problem under high effort cost. Specifically, with disaggregated quota, the revenue maximizing legal landing equals to the quota for each type of fish. Given the technology level, if the price of effort is low enough, fisher will discard the cheap fish and retain expensive fish. If the price of effort rises, ideally no dumping occurs. If the price of effort increases further, then the quotas no longer bind. In the case of Japan, although the TAC is quite information intensive, I believe the TAC system works well in terms of retaining fish resources and solve dumping problem. Because the input control raises the cost of effort to a really high level. Besides, (Mitsutaku Makino, 2011) Fishes and their organizations play a core role in the Japanese fisheries management regime, in both resource and ecosystem conservation. So, Japanese fisherman has a high self-awareness of sustainable fishing.

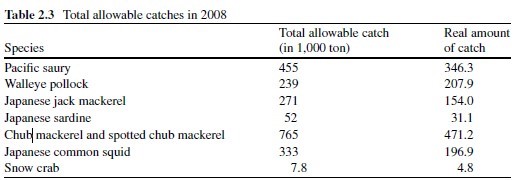

Mitsutaku Makino exposed an interesting data (shown in below table) in his book “fisheries management in Japan”: the real amount of catch in Japan is far below the TAC. I am really interested in the reason of the gap, however, they are not demonstrated in the book. Is it because of the overestimated TAC, effectiveness of input and output control or the economic inefficiency of fishing sector??

Resource: Mitsutaku Makino, fisheries management in Japan: its institutional features and case studies. 2011

Hot repute on fisheries reform

In 2007, a policy report published by an influential think tank suggested dozens of specific policy measures to be implemented by the Japan national government. Several measures have sparked heated debate within the fisheries industry, academics and the government. One point is to introduction of Individual Transferable Quota system to abolish entry barriers to fisheries and made it open to anyone. Actually, Japanese fishers have autonomously introduced IQ, but not explicitly defined ITQS. But the small-scale fishers and processors, spoke out strongly against the report, especially the coastal fisheries open and adoption of ITQ.

The ITQ is similar with the cap-and-trade in carbon emission reduction policy. It is the freely transferable of TAC. The participants can sell the rest part of their unused quota to others. The gap in above tables maybe because of lack of the ITQ, i.e. fishers can transfer the abundant quota. If the quota is fully used, it could be contribute to increase the supply for satisfying the fish production consumption in economic and sustainable way.

However, the small-scale fishers and processors who strongly against claims that decline in the economic efficiency of the fisheries must be addressed, but not through the unrestricted entry of large companies from outside local communities. The adoption of ITQ would destroy these historically established verified systems, and would change the fisheries sector into short-sighted profit-pursuing industry.

Conclusion

We could see that the effectiveness of fish resource management methods in Japan deserves to be highlighted in terms of overcome overexploiting and dumping problem. We always concern about the overexploiting of fish, however, this is not the case for Japan. Its biggest problem is gradually less competitive with other countries in fish catching and the economic inefficiency in fish sector. The fish reforms may aim to solve this problem, but we couldn’t deny that there are profit pursuing incentives. To balance the increasing demand and sustainable supply is always hard. Especially, the fishing policy is not the simply economic problem, but intertwine with political concerns. In Japan, if the “economic efficient” policy shakes its community based fisheries interest, we could understand why fishers say “No”.

Reference:

- Mitsutaku Makino (2011): Fisheries management in Japan: its institutional feature and case studies. Springer

- Matthew A. Turner (1996): Quota-induced discarding in heterogeneous fisheries. Journal of environmental economics and management.

- OECD: Fisheries of Japan: fisheries policy outline for FY2011. White paper on fisheries

- Carl-Christian Schmidt (2000): Fisheries and Japan: a case of multiple roles?