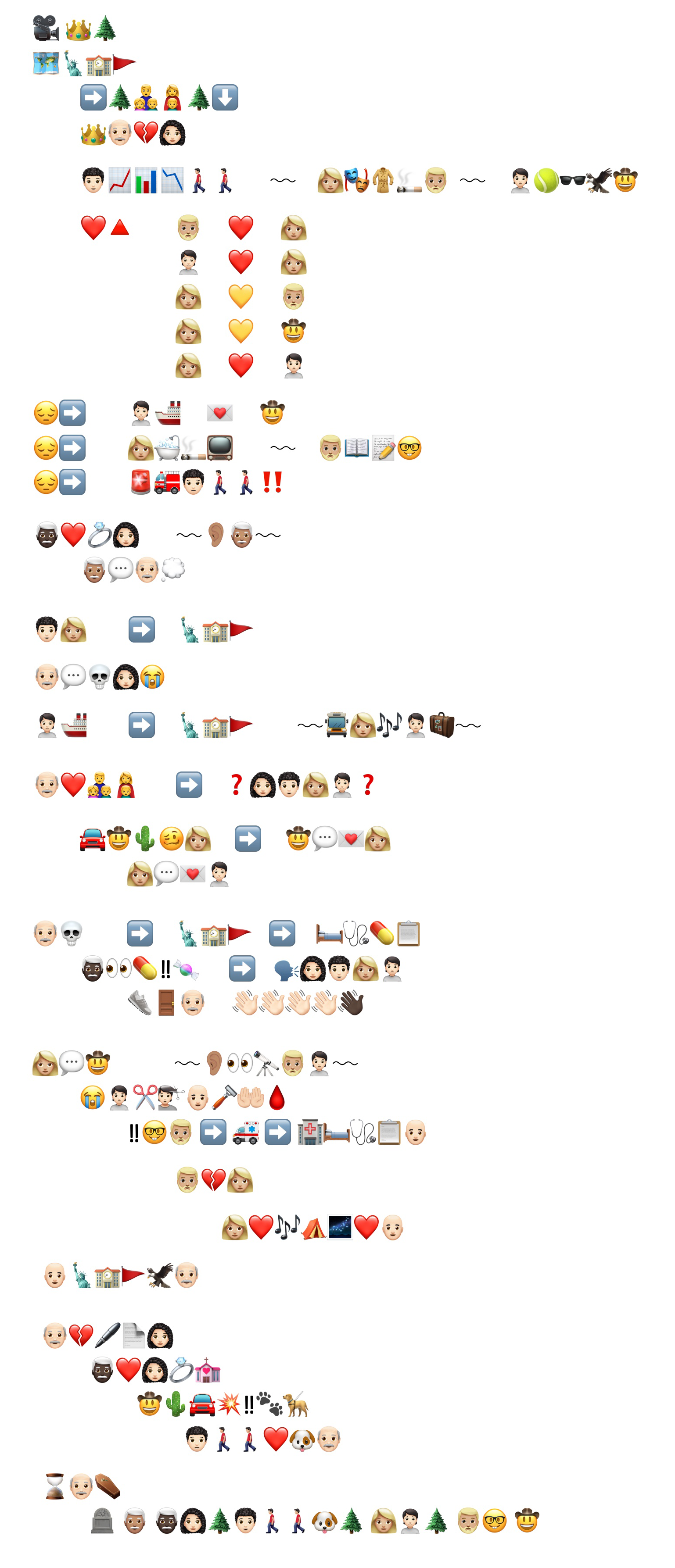

Secondly, I wanted there to be a musical element to my podcast, since music is something that cannot be effectively relayed in text. I could write about music, and theoretically, I could write and read musical notation, but to really understand a melody it needs to be heard. To incorporate music, I decided to attach a playlist to the items in my bag: each item translating to a specific song. The dialogue in the recording attempts to relay how I decided on a song, sometimes there is a clear connection, other times the path that gets me there is strange and wandering. It wouldn’t be fair to call myself an audiophile, (especially in contrast to my partner, Hiller, who co-stars in the audio recording), but my musical knowledge has a notable depth and places me on the periphery of a few music-based “lifeworlds,” (The New London Group, 1996, p. 70) perhaps the 60s psych enthusiasts? Lo-fi/punk/twee appreciation club? Resident indie fan? 90s hip hop day-tripper? Counterculture music historian? To me, it made sense to provide a glimpse into this part of me using the best suited mode. Ironically, Hiller and I provide our own vocal snippets of each song, so even though audio may be the most appropriate mode of communication, understanding the song may require some level of interpretation.

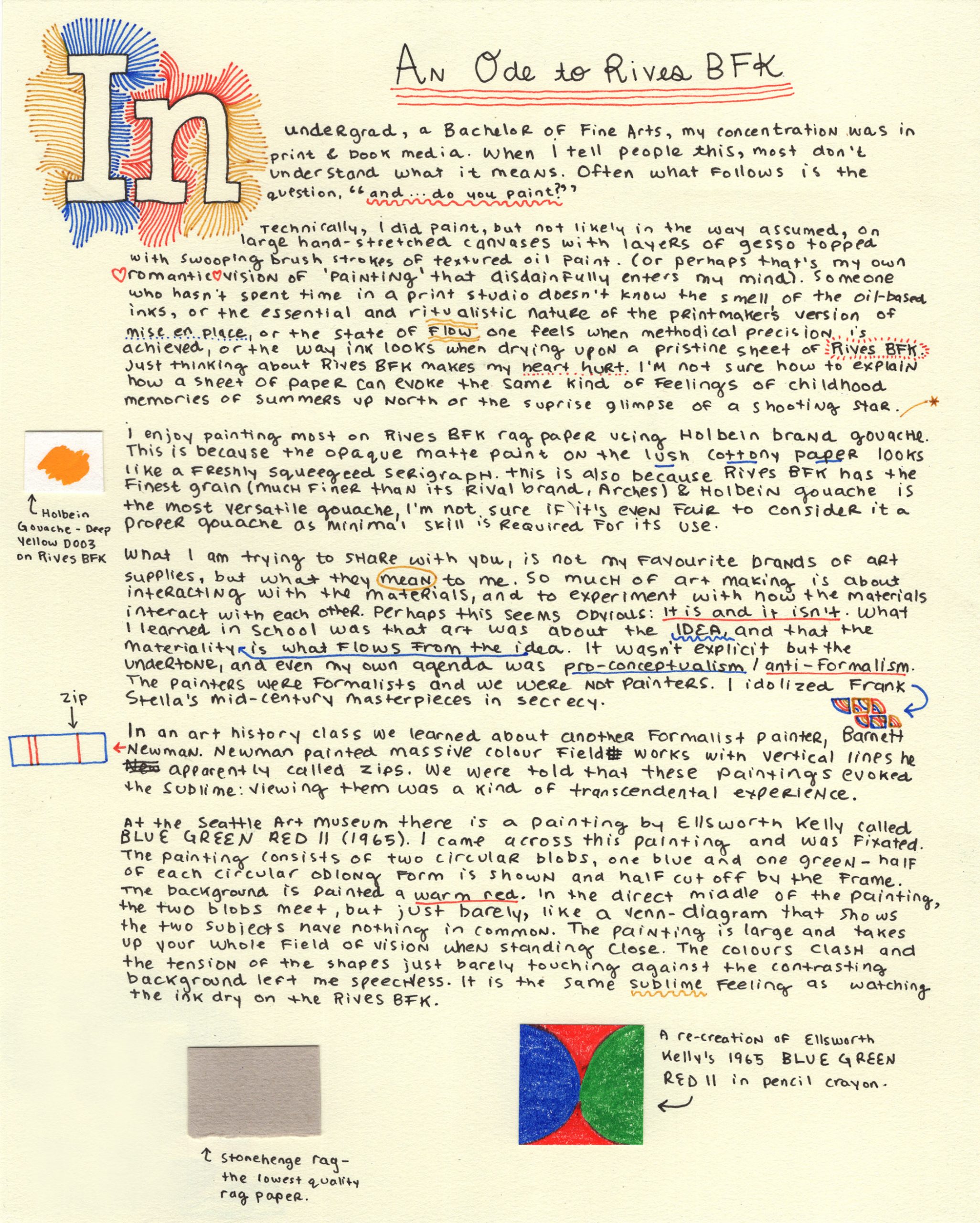

The New London Group’s (1996) concept of “lifeworlds – spaces for community life where local and specific meanings can be made” (p. 70), made me consider which of my lifeworlds I revealed in the initial What’s in my Bag task. I had emphasized an interest in aesthetics, smart design, and functionality, so perhaps it’s evident that I am part of an art and design community or lifeworld, and maybe one can tell that I am a millennial. The Group’s proposition of “a metalanguage of multiliteracies based on the concept of ‘design’” (p. 73) resonated with me. I’ve always felt that there is a close relationship between design and pedagogy. When researching how to develop my education beyond an initial BFA, I considered whether to move in the direction of graphic/information design versus education. I view good design as a method of utilizing aesthetics to clearly transmit complex information in a way that is readily accessible. This is the same premise that led me to education: a desire to identify and design the best methods to communicate complex knowledge.

Reference List

Dobson, T., & Willinsky, J. (2009). Digital Literacy. In D. Olson & N. Torrance (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Literacy, 286-312. Cambridge University Press.

The New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review 66(1), 60-92.

Play List

- Fjallraven bag with the logo removed – Iron Man – Black Sabbath (*Of note: it was edited out, but I had thought of ABBA because of the Sweden connection.)

- Pin with coloured beads – Pocket Calculator – Kraftwerk

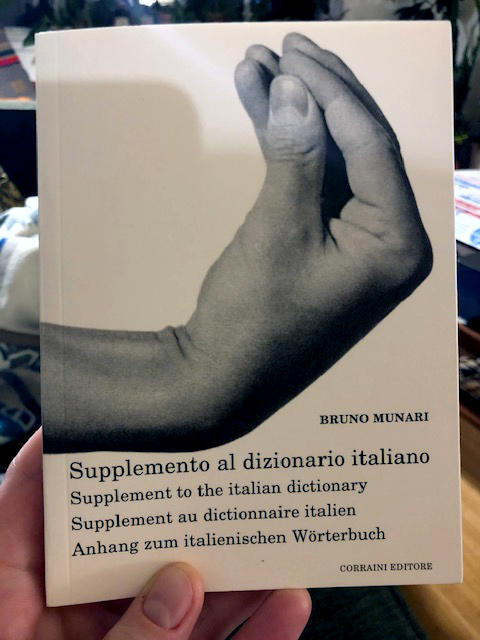

- Hand sanitizer – Postcards from Italy – Beirut

- Leather monographed wallet – Venus in Furs – The Velvet Underground

- Keys with bottle opener and knife – Dead of Night – Orville Peck

- Fingerless gloves, mended – Mother – Plastic Ono Band / Cello Song – The Books ft. Jose Gonzales (*Of Note: Nick Drake is English, not Scottish)

- Reusable bag, mended – Tom Tom Club – Genius of Love (*See Also: Fantasy – Mariah Carey & Fantasy (Cover) – Owen Pallett/Final Fantasy)

- Face mask with flowers – Californication – Red Hot Chili Peppers

- Toque – Age of Consent – New Order

- Measuring tape – Autobahn – Kraftwerk

- Elastoplast Tin with Band-Aids inside – Big Girls Don’t Cry – Franky Valley and the Four Seasons

- Delfonics pencil case with Staedtler Coloured markers – Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds – The Beatles

- Rollbahn notebook – I Felt Like Smashing my Face in a Clear Glass Window – Yoko Ono

- Hand moisturizer – Sibylle Baier – Tonight