Introduction

I initially shied away from this IP, as its focus is on data, graphs, and analysis, which is not my area of expertise. Yet as I read more about Citton’s attentional ecosophy and thought about deep diving into my own attention, my curiosity got the best of me. As I immersed myself into Citton’s (2017) writing, I braced for a dense economic-centric read, and initiated a kind of didactic notetaking practice, which quickly gave way to my standard reading practice of highlighting and marginalia. This text is not tedious economics (in fact, Citton later positions his ideas away from an economics-based perspective, and toward an ecosophical view (pp. 19-23)) – it is surprisingly and thankfully philosophically poetic, akin to French theorists such as Barthes, Baudrillard, Perec and Deleuze and Guatarri (amongst many others).

Citton describes the attention economy as being “another economy” (p. 4); unlike an economy based on the “scarcity of factors of production” (p. 2), the attention economy focuses on the “scarcity of the capacity for the reception of cultural goods” (p. 2). To simplify: an economy fueled by an excess of cultural goods, and a lack of individuals’ attention to consume those goods. Citton hypothesizes that the growth of this other economy will lead to a shift where we (our attentions) will be valued as a sought after good, “in a few years or decades, we will be able to request payment for giving our attention to a cultural good instead of having to pay for the right to access it” (p. 8). There is something expectantly glib about this idea, as though, of course this is the kind of dystopic reality we are on the periphery of/are already in – maybe we can benefit from it. But we are reminded that our attention is not something to commodify, it is much more than a commodity, it is essentially us, who we are, individually and societally.

…attention does not only allow us to secure our ‘subsistence’ by avoiding death, and our ‘existence’ by bringing about the emergence of a unique and unprecedented life form through us; but, above all, it enables us to acquire a greater ‘consistence’ within the relationships that are woven in us. Far from helping us only to continue in being, it enables us to become ourselves (p. 172).

Where My Attention Lies

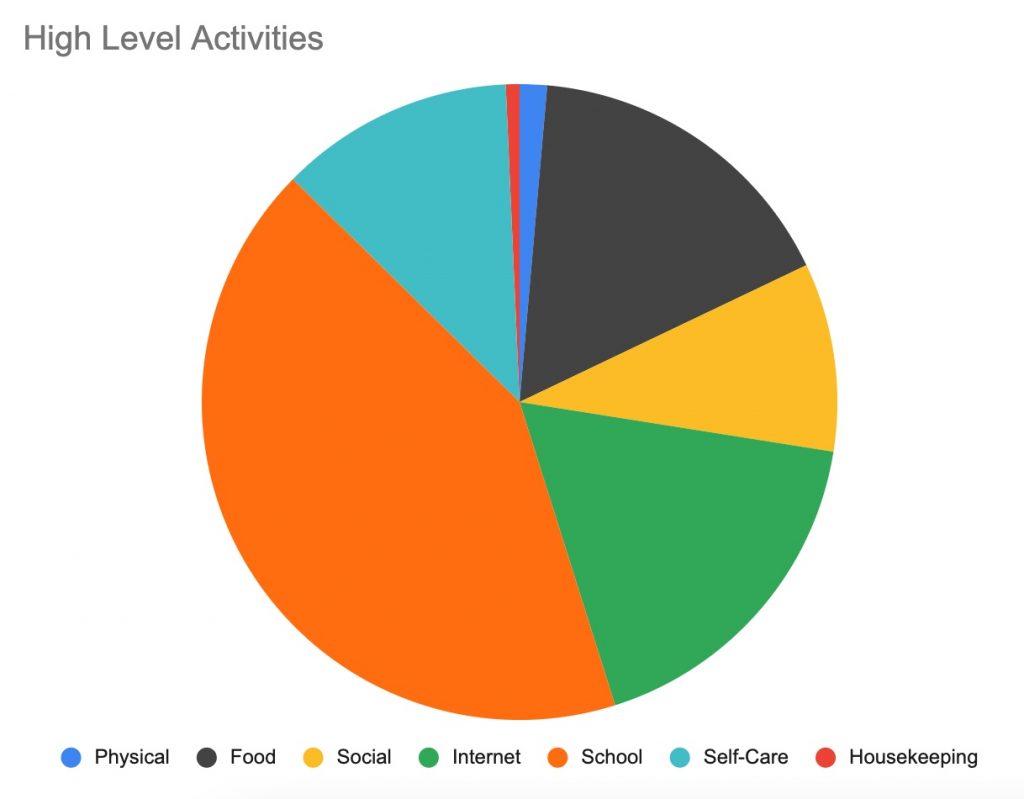

I documented my attentions for a 12-hour period. There are different types of days in my life: a day at the office, a day working from home, a day of errands about the city, a day of adventure, a social day, a lazy day. This day was a schoolwork day, a weekend day, normally reserved for rest and relaxation, but a day I begrudgingly set aside to complete the academic tasks I signed up for. From an emotional perspective, I would describe schoolwork days as a battle with procrastination and guilt, but the data revealed more. To capture a high-level visual on how I spent the day, I went through each attention entry and coded it to pair with a higher-level categorization: Physical, Food, Social, Internet, School, Self-Care, Housekeeping, then translated this data into the pie chart displayed below.

I was surprised and pleased to see that school-related work accounted for almost half of the period, totalling just over 5 hours of work. Additionally, I was dismayed that I spent over 2 hours on the internet – and this means, just on the internet, Googling or streaming content. The “internet” category does not account for all digital activity, nor does it account for school-related internet engagement (which would exist in the ‘school’ category).

Multitasking

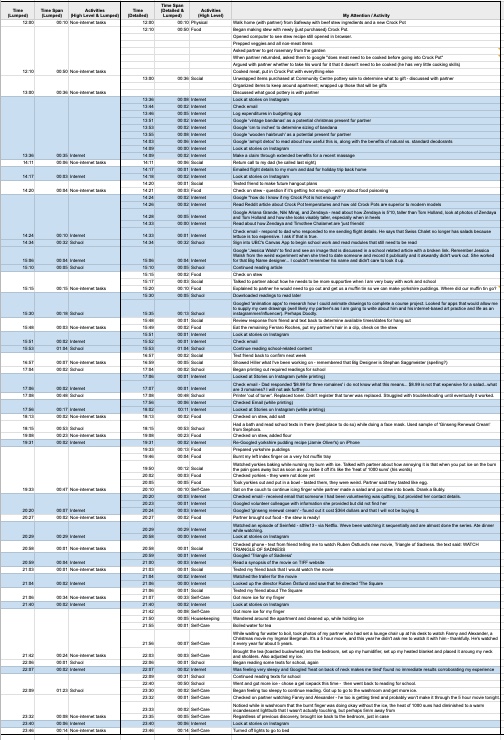

The blue highlighted lines represent internet activity. See Google Sheets document.

Over the 12-hour period, I shifted from another activity toward the internet 15 times – I used my search history to gather accurate data on time and focus of activity. Upon reflection my attention seems frenetic and impulsive, yet in the moment, my outward activity is simply reflective of my own thoughts in flux and my actions feel fluid. De Castell and Jenson (2004) validate this kind of multitasking that is reflective of our technologically dominant culture,

…in fact highly efficient and effective deployments of partial, subsidiary, and intermittent attention strategies routinely used by students, who have learned to do homework while watching television and listening to music on headsets — with that homework being done on a computer whose multiple screens are simultaneously at work and at play, between Internet research, chat programs, word processing, e-mail, and, of course, online games, users switching rapidly among the screens to minimize any loss of time associated with waiting for processing, loading, connecting, and the like (p. 388).

It is true that while waiting I turned my attention to the internet, but this was also my reflexive response to many passing thoughts, some of which, I did not truly care to know more about and quickly abandoned my query. “Google lives off our active and reactive attention, which continually nourish and refine the effectiveness of the formal apparatus put at our disposal. On the other hand, Google tends increasingly to sell our attention, our needs to know and our search choices, to advertisers that the firm allows to short-circuit the effects of our common intelligence…” (2017, p. 9) – Citton’s words remind me that I need to bring awareness to my attention, particularly if my quotidian actions benefit massive corporations by selling a little bit of me for an answer I barely cared to know.

Fluctuation Over Time

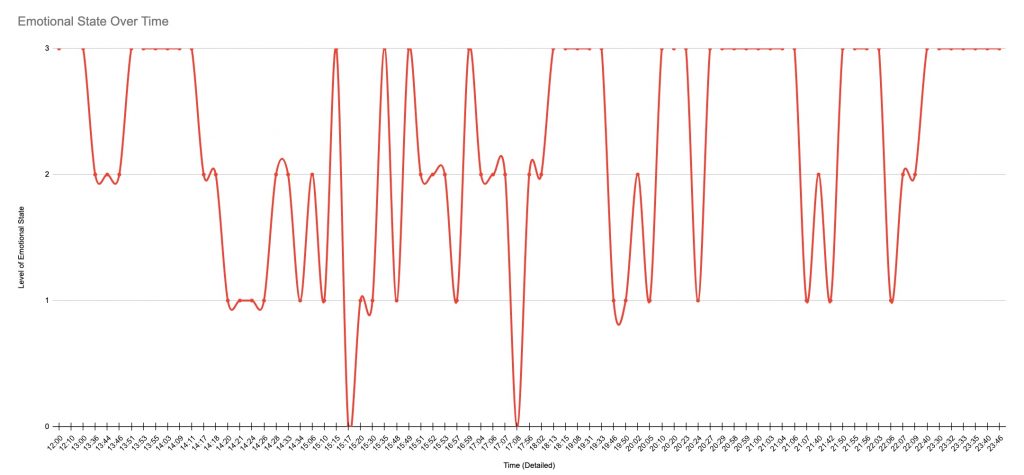

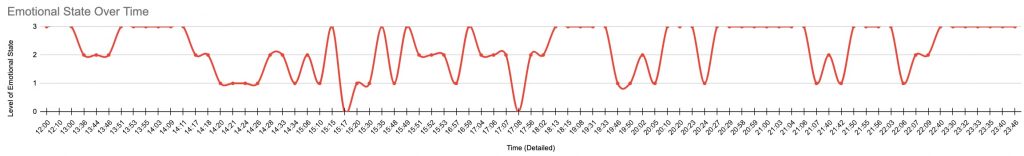

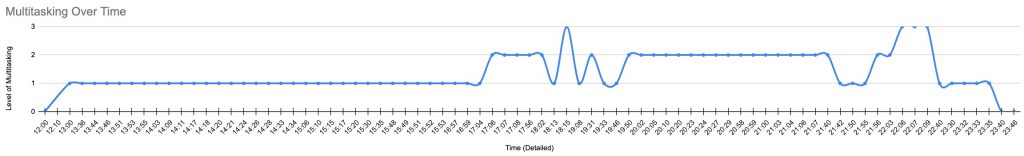

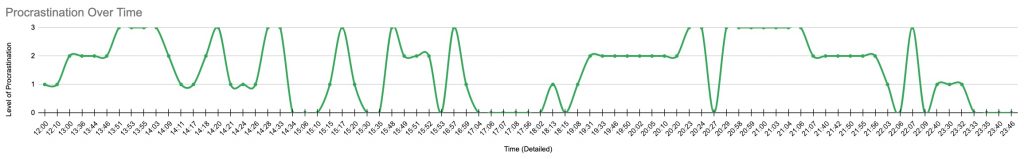

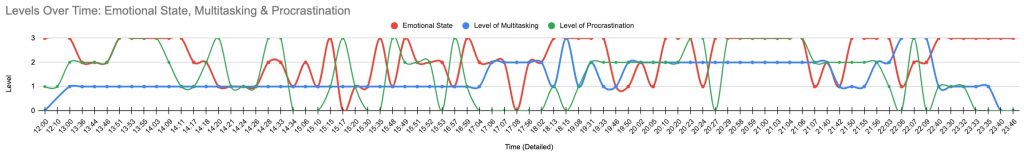

I attempted to code the data I collected to reflect the following levels: my emotional state, multitasking, and procrastination. I used a scale ranging from 0-3. For my emotional state, 0 represented negative emotions and 3 represented the height of positive emotions (ranging from resentful to enthusiastic). For multitasking, 0 represented not multitasking at all, where 3 represented extensive multitasking. For procrastination I was thinking about how my attention best reflected my goal of completing schoolwork for the day, 0 representing not procrastinating at all, and 3 representing extreme procrastination.

Emotional State Over Time

Initially, this chart appears chaotic, as though a regular day is an emotional rollercoaster, but keep in mind, that the emotional range is not extreme, and if the dimensions of the graph are transformed to visually reflect the emotional range, it appears more accurate. Additionally, it was comforting to know, that even during a stressful period (nearing the end of a school semester), I experience regular stretches of general happiness.

Click on images to be brought to the Google Sheets document where the charts can be viewed large-scale.

Multitasking Over Time

Most of the time I was engaged in some level of multitasking. Particularly on this day, as I started the period with learning how to use a new slow cooker and making a stew, so tending to the stew and learning this new device served as a backdrop to all the other activities. There were also times throughout the day where I hyper multitasked (e.g., 6:15pm: Had a bath and read school texts in there (best place to do so) while doing a face mask. Used sample of ‘Ginseng Renewal Cream’ from Sephora.) Why not combine self-care, school, and relaxation all in one –and while the stew is cooking!

Procrastination Over Time

Initially this section was called “distractions” but I changed it to procrastination, as I felt that most of my distractions were intentional acts of avoidance, methods to avoid focusing on my schoolwork, the necessary goal of the day. Those periods where procrastination is at 0 represent when I was able to focus on schoolwork or complete a necessary task for basic functioning.

All Levels Over Time

I worked out all this data specifically so I could compare it to look for correlations, or interesting patterns. Here are some of my initial observations:

- Multiple times there is a peak in red (emotional state) followed shortly after by a peak in green (procrastination) upon inspecting the data, it appears in these cases I did schoolwork, and then, almost as a reward, right after I did something unimportant, like Google a passing thought.

- There is an overall similar flow with red (emotional state) and green (procrastination). I believe this is because both levels over time are directly emotionally based.

- Blue (multitasking) is more consistent than the other two that are directly reflective of my emotions. But the act of multitasking is more stable, displaying longer timeframes of similar states – during these times, I may be jumping around to different activities, but they are in the same realm (e.g., all on the internet, or cooking different parts of a meal).

- During periods of steady blue (multitasking) there seems to be more activity with red (emotional state) and green (procrastination), yet when blue is more active, red, and green seem less so – as though steady activity, allows my mind to wander, but as my multitasking abilities shift, my emotions are less active as I focus on the change.

Conclusion

The act of reading Citton’s text, then closely analyzing my own attention, has guided me to look carefully at what exactly my attentions are, how they flow, how they are affected and how they affect, and their deeper connections. These close observations have taught me more about myself and how I interact with my reality. Part of Citton’s turn to an attention ecosophy as opposed to the notion of an attention economy points to attention’s nature of being relational/interactive/connected/entangled. “It represents the essential mediator charged with assuring my relationship with the environment that nourishes my survival…” (p.22). Learning about an ecosophy of attention through a close observation of my own attentions enables another way for me to perceive my place in this world, an awareness that I hope provokes me to remain attentive. As a reminder, we can always refer to Citton’s tenth maxim of attentional ecosophy:

10. Learn to devote yourself, at different times, to hyper-focusing, open vigilance and free-floating attention. Even more than the ability to concentrate, good attentional health is characterized by an aptitude for modulating your level of attention to the situation at hand. It is just as essential to be able to immerse yourself in methods of sustained hyper-focusing, which make us impervious to any external stimulus, as it is to sweep broadly across the field of possibilities to note something entirely new, or to allow your free-floating attention to transgress the barriers of habit (p. 180).

Addendum

Check out the Google Sheets document for more detailed views of the charts and graphs shown as well as further visualizations of the data, including:

- High-Level Activities lumped into even broader categories: School, Internet, Non-Internet Tasks (everything else)

- Digital vs. Non-Digital Activities

- Pie Chart of Emotional States

- Bar graph of key words and their levels of usage

References

Citton, Y. (2017). The ecology of attention. John Wiley & Sons.

De Castell, S., & Jenson, J. (2004). Paying attention to attention: New economies for learning. Educational Theory, 54(4), 381-397.