Check out my group’s completed Digital Learning Resource focused on Transforming a New Media Curriculum Using A DIY Inclusive Makerspace Approach.

Check out my group’s completed Digital Learning Resource focused on Transforming a New Media Curriculum Using A DIY Inclusive Makerspace Approach.

Check out the Digital Learning Resource I created, focused on SPACE, and made using Twine. By ‘space’, I mean both the physical and digital spaces of a makerspace classroom

Here I explore how the ways we exist in different environments affect each of us in unique and impactful ways. With this understanding, I look at aspects of design to think about how we can design spaces of learning with intention and from a place of equity, diversity, inclusion, decolonization and anti-racism. I also consider how to incorporate digital spaces in meaningful ways and put our minds to thinking about how we can transform the space, shape and form of education as we currently know it, to something new, innovative, exciting and effective.

Ruha Benjamin (2019) examines instances where human subjectivities permeate algorithmic artificial intelligence (AI). At first, this presents as surprising phenomena, but upon consideration, it only makes sense that an invention made by humans would be created through a subjective lens of understanding, and therefore through inherent biases. Benjamin extends this idea further, “they learn to speak the coded language of their human parents – not only programmers but all of us online who contribute to ‘naturally occurring’ datasets on which AI learn” (p. 62). Again, if we pause to critically think about AI and how it functions, this problem, although perhaps not explicit, is not hidden.

In his advocacy for critical media education, Buckingham (2019) explains the importance of applying logic and analysis to see beyond the surface and reminds us that critical thinking “requires us to look at what is included and excluded from the frame, and what the consequences of this might be” (p. 45). This sentiment asks us to take a closer look at the media and technology we engage with, and to consider whether our usage invokes implicit ethical implications, rather than blindly engaging with novel technologies.

The awareness of potential weaknesses embedded in technology should not result in educational practices that shy away or serve as a “prophylactic against [it]” (Buckingham, 2019, p. 52); this mindfulness should provoke educators to critically consider how they choose to integrate technology and new media to ensure they are used meaningfully rather than as superfluous gimmick. In conversation with Dr. Lori MacIntosh, Brandon Rodriguez, an Education Specialist with NASA, reflects on his experience educating throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. He shares methods for offline learning through basic experiments using household objects, rather than employing novel technology that further add to the excessive amount of screentime students were experiencing. He describes growing “alarmed by how many teachers were just shooting out options for technology,” (MacIntosh, n.d.) when the differences between various apps were insignificant and were likely obscuring educational outcomes that could be reached in simpler ways. It is not that Rodriquez chose not to use technology at all, rather, he chose to use it when it enhanced learning, and in balance with the realities of his students that may have challenges with access.

Another example of a balanced approach to integrating technology into education is illustrated by Champion, et al. (2020) through their in-person, hip hop-focused STEM camp. The camp’s design included an attention to the physicality of the space, availability of low-cost materials for DIY construction, instruction, and use of high-tech and analogue technologies for creating and re-mixing sound, and an application of curriculum design, that considered the interaction and collaboration amongst students. In this example, as well as with Rodriguez’s practices, new technology is not simply accepted as a panacea for educational obstacles, instead it is carefully integrated in ways that support hybrid learning environments.

References:

Benjamin, R. (2019). Race after technology: Abolitionist tools for the new jim code. Polity Press.

Buckingham, D. (2019). The media education manifesto. Polity.

Champion, D. N., Tucker-Raymond, E., Millner, A., Gravel, B., Wright, C. G., Likely, R., Allen-Handy, A. & Dandridge, T. M. (2020). (Designing for) learning computational STEM and arts integration in culturally sustaining learning ecologies. Information and Learning Sciences, 121(9/10), 785-804.

MacIntosh, L. (Host). (n.d.). Interview with Brandon Rodriguez, Education Specialist, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, NASA (No. 6) [Audio podcast]. University of British Columbia, in ETEC 531.

Written by: Marshall Boardman; Lisa Burnette; Erin Marranca; Miguel Rojas Ortega

The British Columbia English Language Arts curriculum on New Media for Grade 12 (British Columbia Ministry of Education, 2018) provides a comprehensive framework for students to explore the dynamic world of digital citizenship. However, by focusing on the following four key areas, (1) mental health and wellness, (2) climate change and energy literacy, (3) critical media literacy, and (4) inclusivity in physical and digital spaces, we aim to jam this curriculum to address issues related to cyberbullying and body image, climate change and sustainable practices, critical analysis of media, and inclusivity of race, gender, neurodiversity, and ableism.

In line with the philosophy of constructionism, students are encouraged to become active creators and contributors in the digital landscape. Through the lens of digital citizenship, they will navigate the complexities of advocacy, community building, propaganda, and manipulation in an increasingly globalized society. Our enhanced curriculum will further emphasize the influence of land and place of identity, and cultural connections, highlighting the importance of inclusivity and recognizing the rich heritage of First Peoples. Our curriculum aims to empower students to express their opinions with evidence and achieve purpose by incorporating a holistic critical media education and promoting an inclusive learning environment. To accomplish these goals, our curriculum jamming will leverage the theory of makerspaces, providing students with hands-on, collaborative learning experiences to explore, create, and problem-solve using various analogue and digital tools and materials.

We aim to form a pedagogical approach that radically transforms standardized education delivery formats. At the outset, we call for a shift in traditional education methods by proposing a constructionist-informed, makerspace philosophy to be applied not only to curriculum design but also to the design of physical and digital learning environments. Many makerspaces are created and maintained collectively by users of the space (UBC MET, 2022); we reflect this practice in our approach, where learners are empowered to be active designers and creators of their own learning and learning environments. From this maker-centred perspective, we propose addressing curriculum from a place of learning through creativity, which can be approached at different angles that are cognisant of learner ability and socioeconomic constraints. These angles are LO FI, MID FI and HI FI DIY (do-it-yourself). LO FI DIY engages with making from a low-or-no-cost and low-or-no-tech perspective, MID FI DIY integrates low-to-mid-cost and easily accessible technology, and HI FI DIY connects learners with more advanced technologies and equipment that may have higher cost associations.

In the same way that we are focused on changing the shape and experience of education, we also aspire to modernize curriculum content by borrowing from culture-jamming tactics popularized in the 1990s. We intend to employ a “critical attitude and participatory, creative form of activism” (Jenkins, 2017) to analyze, break apart, and jam current curriculums with the missing content that we view as essential to modern education. Firstly, the pervasive nature of media dictates how vital it is to incorporate critical media literacy throughout all aspects of education, especially within subjects of new media. Our pedagogy advocates for a holistic approach to critical media literacy to provide learners with the critical thinking skills to actively participate in media consumption and production in meaningful, democratic, and mindful ways.

Another core element of our approach emphasises inclusivity, which demands that an awareness and empathy of the diverse identities, cultures and abilities of learners is continuously exercised and interwoven throughout the format, experience, and content of education. We recognize the urgency in which issues of systemic racism and inequalities must be addressed in modern educational curriculum. With this in mind, we apply various EDIDA (Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, Decolonization and Anti-racism) frameworks to identify and mitigate systemic oppression and persistent colonial structures.

By applying our pedagogical methodology to challenge, subvert, and modernize the BC Grade 12, New Media curriculum, we aim to further develop and solidify our ideas to be able to transform them into a robust and comprehensive manifesto that calls for a much needed shift in education.

The foundational resources that will support the artifacts we create include works that inform critical media pedagogy (Kellner & Share, 2019; Buckingham, 2019; Freire, 1970), as well as scholarly texts that address constructionism and makerspace methodologies (Papert, 1988; Halverson and Sheridan, 2014), inclusivity in makerspaces (Seo and Richard, 2021; UBC MET, 2022) and EDIDA frameworks, such as the BCIT Anti-Racism Framework (BCIT, n.d.) and the First Peoples Principles of Learning (First Nations Education Steering Committee, n.d.; Brayboy & Maughan, 2009). Below, we provide further context for our inclusion of these foundational texts.

As society and culture have considerable influence on knowledge development, the media inevitably shapes young people’s ideas and beliefs. We have focused on themes of media literacy education and critical media pedagogy because of their immediate relevance and importance in shaping students’ understanding of media and culture. Certain media’s exploitative and manipulative nature has resulted in many young people receiving misleading information. This is why educators must guide students in constructing a framework for “understanding and decoding all forms of media culture from a critical perspective” (Kellner & Share, 2019, p. xii). By integrating media education throughout our curriculum design, educators can foster critical thinking among their students by creating an atmosphere where multiple perspectives on media and culture are openly discussed. The teaching and learning considerations for the resource we are designing include culturally relevant lessons and anti-colonial texts to ensure a comprehensive and inclusive approach. The rationale for this topic and direction is supported by the need for students to develop a critical understanding of media, question media narratives, and understand the relationship between power and information in the media. Drawing upon the philosophy of critical pedagogy developed by Paulo Freire (1970), critical media pedagogy sheds light on the hierarchical power structures embedded in society, examines their representation in contemporary media, and engenders learners to consider how neutrality, bias, and transparency influence media coverage.

In reaction to the inadequacy of current media literacy, Buckingham (2019) advocates for an expanded form of media literacy education that is holistic, pervasive, and extensive. He “argues for a media education as a basic prerequisite of contemporary citizenship – and hence as a fundamental entitlement throughout the education system” (p.16). Instilling a comprehensive “media education”, rather than teaching media literacy as an isolated subject, can allow for integration throughout the curriculum to match the pervasiveness of media presence itself.

Ideally, a holistic critical media education enables students to become active participants of media rather than passive consumers. Critical media pedagogy serves this goal by encouraging students to produce their media as a means of self-expression. From a constructionist perspective, creating something real and concrete can extend knowledge construction. Papert (1988) articulates that “constructivism is the idea that knowledge is something you build in your head. Constructionism reminds us that the best way to do that is to build something tangible – something outside your head – personally meaningful” (p. 13). The maker movement pulls from constructivist and constructionist theories and inspires participatory learning.

Halverson and Sheridan (2014) explain that “the maker movement refers broadly to the growing number of people who are engaged in the creative production of artifacts in their daily lives and who find physical and digital forums to share their processes and products with others” (p. 496). The designated places where people come together to create are known as ‘makerspaces’ and are designed as workshops with various stations of workspaces, social spaces, and specialized equipment (e.g., woodworking tools, 3D printers, printmaking set-ups, CNC machines, etc.). Within a session of UBC’s MET Anti-Racism Speaker Series (2022), Zoe Branigan-Pipe expands on the importance of the physicality of the makerspace itself. We believe an educational environment that adopts a makerspace philosophy can allow for a critical media pedagogy that cultivates active and participatory learning.

For a multifunctional creative environment to be conducive to learning for all learners, thoughtful attention to inclusivity is required. Seo and Richard (2021) address this challenge directly through the design of a framework informed by Universal Design (UD) principles titled “SCAFFOLD” and assert that the framework “considers gender equality, cultural inclusivity and accessibility to support the inclusion of intersectionally diverse learners with diverse abilities in makerspaces” (p. 796). The SCAFFOLD acronym encompasses eight principles for consideration when designing inclusive makerspaces: Simplicity, Collaboration, Accessibility, Flexibility, Fail-safe, Object-Oriented, Linkability and Diversity (p. 804).

The application of SCAFFOLD, as well as additional EDIDA frameworks help us to define a foundation that supports inclusivity. These frameworks emphasize the importance of recognizing diverse identities, cultures, and abilities among learners, and work to actively mitigate systemic oppression. The BC curriculum already integrates competencies related to understanding the influence of land, practising responsible digital citizenship, and evaluating the impact of literacy and new media elements; we want to expand these ideas further. We are looking at BCIT’s Anti-Racism Framework (n.d.), which actively acknowledges and works towards eliminating all forms of racism within a community.

The First Peoples Principles of Learning (FPPL) framework also represents a fundamental shift in educational paradigms, emphasizing Indigenous wisdom and perspectives in learning. The FPPL framework draws on the rich traditions of Indigenous communities worldwide, rooted in holistic learning, reciprocity, and environmental interconnectedness (First Nations Education Steering Committee, n.d). Western educational paradigms often follow linear trajectories, while Indigenous worldviews perceive learning as a circular and holistic endeavour (Brayboy & Maughan, 2009). The FPPL framework contributes to more equitable, meaningful, and respectful educational experiences by valuing Indigenous wisdom and culture and respecting local contexts. By expanding on and incorporating these frameworks, we aim to disrupt the selected curriculum and provide a robust foundation that supports inclusivity and addresses systemic racism and inequality.

Our digital learning resource will be in the format of a website. It will be designed to empower educators with the tools, knowledge, and strategies to revolutionize the Grade 12 New Media curriculum through critical media literacy and makerspace education. This resource addresses the need to equip students with essential skills to navigate an increasingly digital and complex world while challenging the status quo and promoting equitable learning experiences.

Website as the Medium

Our website is the central hub for educators seeking to transform their teaching approach. This format will ensure accessibility, ease of use, and compatibility with various devices. Google Sites is chosen for its intuitive interface and integration with other Google apps, facilitating seamless customization and collaboration.

Curriculum Jamming

We will provide educators with a clear roadmap to disrupt and critically engage with the standard curriculum by including detailed explanations of curriculum areas that will be jammed, such as mental health, climate change, critical media literacy, and inclusivity. Educators will gain access to provocations and activities that encourage students to question norms and explore new perspectives.

Resource Library

Our resource library will house many materials, including lesson plans, worksheets, templates, and interactive digital resources. These resources are designed to be adaptable to individual classroom needs. Additionally, a glossary will help educators grasp key concepts related to critical media literacy and makerspace education.

Inclusivity and Equity

We aim to emphasize inclusivity and equity by providing strategies for educators to create inclusive classrooms. Guidance on incorporating EDIDA frameworks and addressing systemic racism will be included. Our resource is committed to promoting diversity, addressing inequalities, and fostering an environment where all students can thrive.

Interactive Participation

We value the input and experiences of educators using our resource. An open Padlet embedded in the site will allow educators to share ideas and collaborate. Google Forms will facilitate the submission of feedback and suggestions, creating an ongoing dialogue for continued improvement.

Lesson Plan Templates / Provocations

Educators will find ready-to-use lesson plan templates and provocations within our Resource Library. These resources are designed to engage students in critical media analysis and makerspace projects, fostering creativity and critical thinking.

Makerspace Toolkits

Our comprehensive makerspace toolkits will cater to diverse learning styles. Educators can choose from text-based guides, interactive digital resources, visually engaging zines, or insightful podcasts. These toolkits aim to empower students to explore, create, and problem-solve using digital and analogue tools.

Our digital learning resource is a catalyst for transformative education. By equipping educators with the means to disrupt traditional curriculum norms, we empower them to foster critical media literacy and makerspace education while promoting inclusivity and equity in the classroom. This resource is a testament to our commitment to reimagining education for the benefit of all students.

References:

BCIT (n.d.). Anti-Racism Framework. https://www.bcit.ca/anti-racism-framework/

Brayboy, B. M. J., & Maughan, E. (2009). Indigenous knowledges and the story of the bean. Harvard Educational Review, 79(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.79.1.l0u6435086352229

British Columbia Ministry of Education. (2018). English Language Arts: New Media 12. https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum/english-language-arts/12/new-media

Buckingham, D. (2019). The media education manifesto. Polity.

First Nations Education Steering Committee. (n.d.). First Peoples Principles of Learning. http://www.fnesc.ca/first-peoples-principles-of-learning/

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed (MB Ramos, Trans.). New York: Continuum, 2007.

Halverson, E. & Sheridan, K. (2014). The maker movement in education. Harvard Educational Review, 84(4), 495-504.

Jenkins, H. (2017, October 30). What do you mean by “culture jamming”?”: An interview with Moritz Fink and Marilyn DeLaure (part one). Confessions of an Aca-Fan.

Kellner, D. & Share, J. (2019). The critical media literacy guide: Engaging media and transforming education. (Vol. 2). Brill.

Papert, S. (1988). A critique of technocentrism in thinking about the school of the future. In Children in the information age (pp. 3-18). Pergamon.

Seo, J. & Richard, G.T. (2021). SCAFFOLDing all abilities into makerspaces: A design framework for universal, accessible and intersectionally inclusive making and learning. Information and Learning Sciences, 122(11/12), 795-815.

UBC MET. (2022, October 20). UBC MET: Inclusive Makerspace and 21st Century Educational Technology [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0-5UK5WZAx4

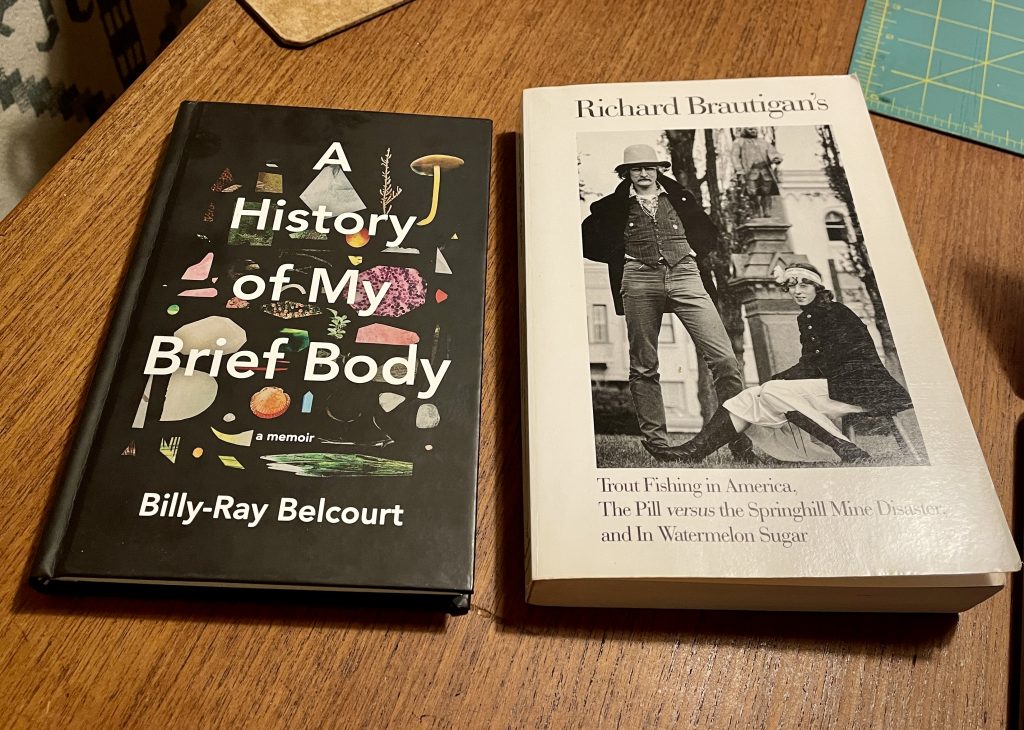

Rather than rummaging through my memory of (many) recent viewings, I searched my recollection for media that elicited profound affect, and landed on Billy-Ray Belcourt’s (2020) novel, A History of My Brief Body. Belcourt’s writing is a multilayered collage of short stories, autobiographical prose, poetry, narrative, and societal critique. His storytelling is juxtaposed with a sharp criticism of colonial Canada, interspersed with references to media such as film, literature, and critical theory. Throughout A History of My Brief Body, Belcourt, a young queer Indigenous writer from the Driftpile Cree Nation (Belcourt, n.d.) located in northern Alberta, explores his identity through the intersections of queerness and Indigeneity. The complexity of A History of My Brief Body’s form is reflective of intersectionality as, ‘a multifaceted perspective acknowledging the richness of the multiple socially-constructed identities that combine to create us as a unique individual” (Lind, as cited in Hill Collins & Bilge, 2016, p. 89).

A History of My Brief Body shares Tuck and Gaztambide-Fernández’s (2013) refusal to comply with settlers’ desire to quiet their anxiety (p. 86), or “comfort their dis-ease” (p. 86). Settlers in Canada are warned of the discomfort of reconciliation, and Belcourt unapologetically provokes the necessary kind of discomfort that is often missing in corporate and academic Truth and Reconciliation initiatives. He writes, “I wonder: How will we ever look white people in the eyes and not periodically see our mangled bodies? This isn’t hyperbole. We have Canadian citizenship, of course, and as citizens we will remember how to participate in the world, but we are still the hunted” (2020, p. 155). Belcourt’s uncensored narratives of being Indigenous and queer in Canada are explicitly written and reveal a vulnerability, “to be queer and NDN is paradoxical in that one is born into a past to which he is also unintelligible. I wasn’t born to love myself every day” (p. 28).

Trout Fishing in America by Richard Brautigan (1989), first published in 1967 is similar in form to A History of My Brief Body – it is a series of short stories and poetry woven together. It is difficult to describe exactly what “Trout Fishing in America” is – it is often presented as different characters, or as an event, or as an undefined descriptor; its repeated usage evokes a humourous absurdity. As with Belcourt, Brautigan’s writing reveals the intimate innerworkings of the writer’s mind, but Brautigan’s content is playful, naïve and untethered to reality.

Although occasionally revealing nuances of current society, Brautigan’s writing does not display intersectionality or an intersectional understanding of self. Brautigan, a white male living and writing as a beat poet and ‘hippy’ in the 50s and 60s (Poetry Foundation, 2023), likely did not possess a self-awareness informed by “interlocking systems of oppression” (Razack as cited in Jeppesen and Petrick, 2018, p. 15) as his position in society did not subject him to significant oppression.

References:

Belcourt, B. R. (2020). A history of my brief body. Penguin Random House.

Belcourt, B. R. (n.d.). About Me. Billy-Ray Belcourt. https://billy-raybelcourt.com/

Brautigan, R. (1989). Richard Brautigan’s Trout fishing in America; The pill versus the Springhill mine disaster; and, In watermelon sugar. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Hill, C. P. & Bilge, S. (2016). Intersectionality. Polity.

Jeppesen, S., & Petrick, K. (2018). Toward an intersectional political economy of autonomous media resources. Interface: A Journal for and About Social Movements, 10(1-2), 8-37.

Poetry Foundation (2023). Richard Brautigan 1935–1984. Poetry Foundation. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/richard-brautigan

Tuck, E., & Gaztambide-Fernández, R. A. (2013). Curriculum, replacement, and settler futurity. Journal of curriculum theorizing, 29(1).

This lesson utilizes the concept of culture jamming, to first encourage Bachelor of Education students to ‘jam’ a colonialist-informed digital learning resource by creating an alternative resource, then to expand this practice when looking at the scope of their own curriculum. Culture jamming is described as “a collection of tactics, as well as a critical attitude and participatory, creative form of activism” (Jenkins, 2017). Within this lesson, the instructor guides a critical exploration of what initially presents as reliable information. This lesson is cognizant of Buckingham’s (2019) notion of media education and integrated throughout are prompts to encourage critical consideration of the information presented, and research practices to ensure information is factual and that learners have considered the biases inherent in their findings.

Instructions for learners:

References:

Buckingham, D. (2019). The media education manifesto. Polity.

Jenkins, H. (2017, October 30). What do you mean by “culture jamming”?”: An interview with Moritz Fink and Marilyn DeLaure (part one). Confessions of an Aca-Fan.

Stuart Hall (1997) describes the immense complexity that exists within language: “…in order to say something meaningful, we have to ‘enter language’, where all sorts of older meanings, which pre-date us, are already stored from previous eras, we can never cleanse language completely, screening out all the other hidden meanings which might modify or distort what we want to say” (p. 17). It is that depth of shared understanding that allows for bonds to form between strangers, and that shapes cultures at micro and macro scales. Applying this notion to our current reality, where an increasing enormity of digital content is generated and circulated via new media, I think about how languages and cultures are developing and changing in rapid acceleration. So, how much of what we learn today is impacted by access to and engagement with new media? Everything?

If we also consider Foucault’s notion of discourse, the surrounding dialogue, opinions, and media content that, “constructs the topic. It defines and produces the objects of our knowledge. It governs the way that a topic can be meaningfully talked about and reasoned about” (p. 29), we understand that engagement with new media contributes to the rapid production of emerging discourse. Furthermore, as Hall explains, “…not only is knowledge always a form of power but power implicated in the questions of whether and in what circumstances knowledge is to be applied or not. This question of the application and effectiveness of power/knowledge was more important, than the question of its ‘truth’” (p. 33). Or rather, that knowledge generated through discourse, produces power, and in a sense, that power allows the knowledge to become truth, regardless of if it actually is. This suggests that not only is our learning impacted by our interactions with new media, but the power it holds – a power largely driven by AI algorithms, that “are by no means neutral, or automatically objective or truthful” (Buckingham, 2019, p. 48) – is actively forming and circulating new truths.

In opposition to this unruly power, the acceleration of new media dictates future pedagogies that focus on the development of critical thinking skills. Through this lens, we can understand the necessity of Buckingham’s (2019) call for a holistic form of media education, and Kellner and Share’s (2019) guide that sheds light on power dynamics inherent in media (new and old) by empowering educators and learners with the knowledge required to critically engage.

References

Buckingham, D. (2019). The media education manifesto. Polity.

Hall, S. (1997). The work of representation. Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices. 2, 13-47.

Kellner, D. & Share, J. (2019). The critical media literacy guide: Engaging media and transforming education. (Vol. 2). Brill.