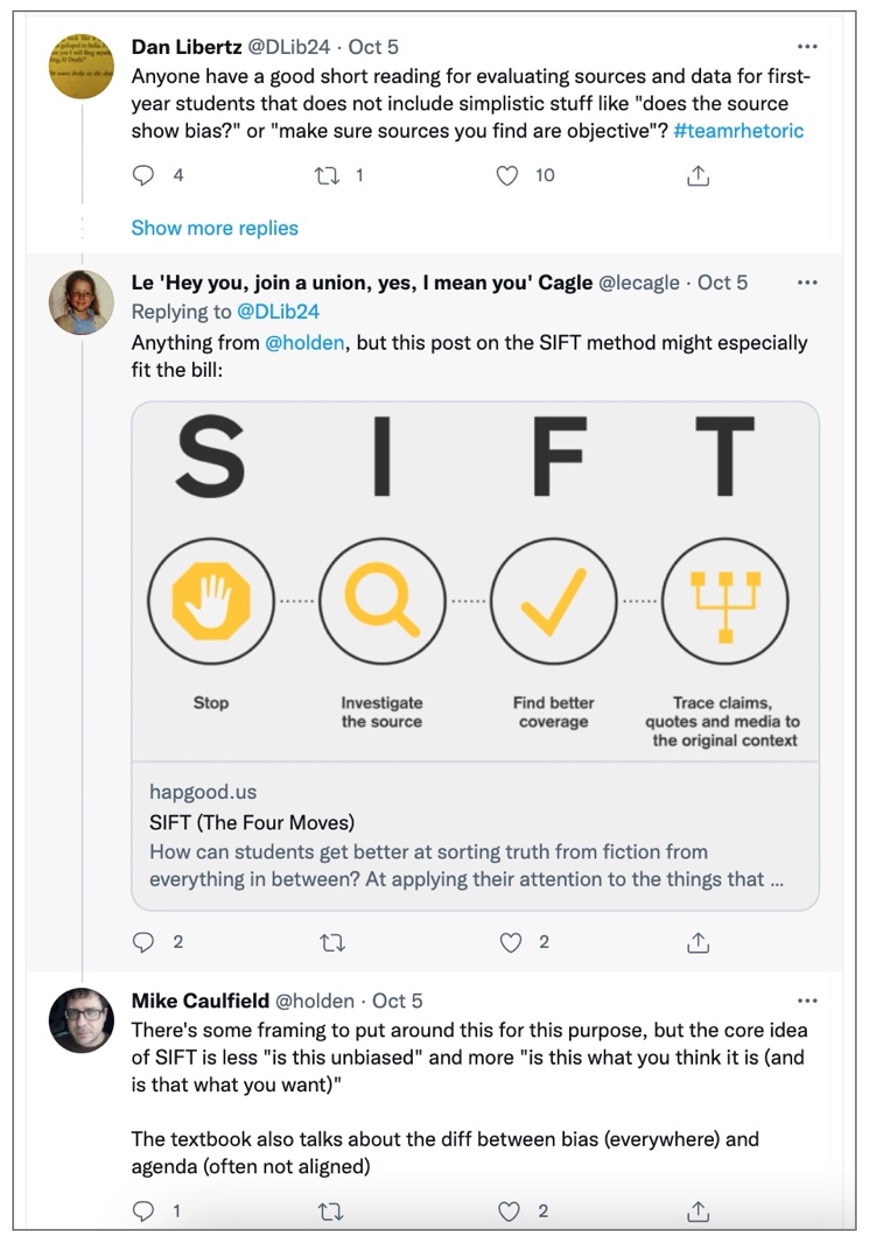

View slideshow here.

Overview

I find it useful to introduce a new concept with a high-level summary of what it encompasses, then delve into the details and intricacies that help initiate the construction of a deeper understanding. In this case, after the high-level view, we will look at what specifically new materialism (NM) is not, to direct us to what it might be. We will then look at the keywords associated with NM as this distinctive language allows us to understand the key concepts of the theory and eases our entry into the “semiotic domain” (Gee, 2007, p. 18) of NM. We will conclude with an example that employs a new materialist perspective and suggests that perhaps this theory is not so new.

Slide One: High-Level Summary

Javier Monforte (2018) breaks down NM into what they call “two synchronized moves” (p. 380). The first move indicates an attention on the relational aspects of things, rather than simply the thing itself. Monforte further illustrates the first move as a “shift from essentialism to emergent immanent relationality. Contrary to the view that entities have essential attributes and ontological integrity that precede their relations, it stands out that all entities emerge from these relations” (p. 380). The second move identifies that the things in question, are in fact, all things: people, animals, places, ideas, buildings, objects. “The latter move consists of acknowledging that not only humans, but also non-humans (both organic and inorganic) have agentic and performative capacities” (p. 380).

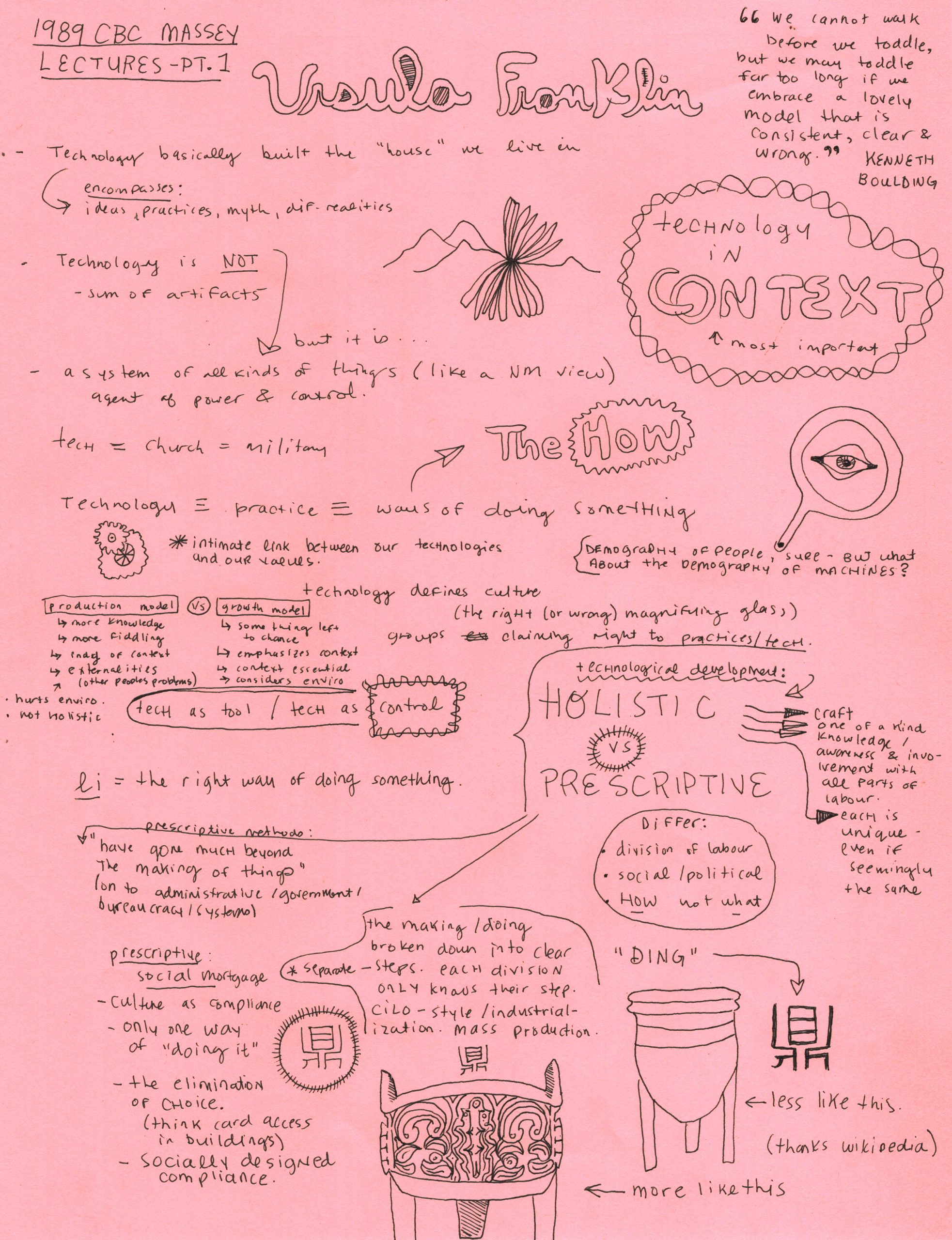

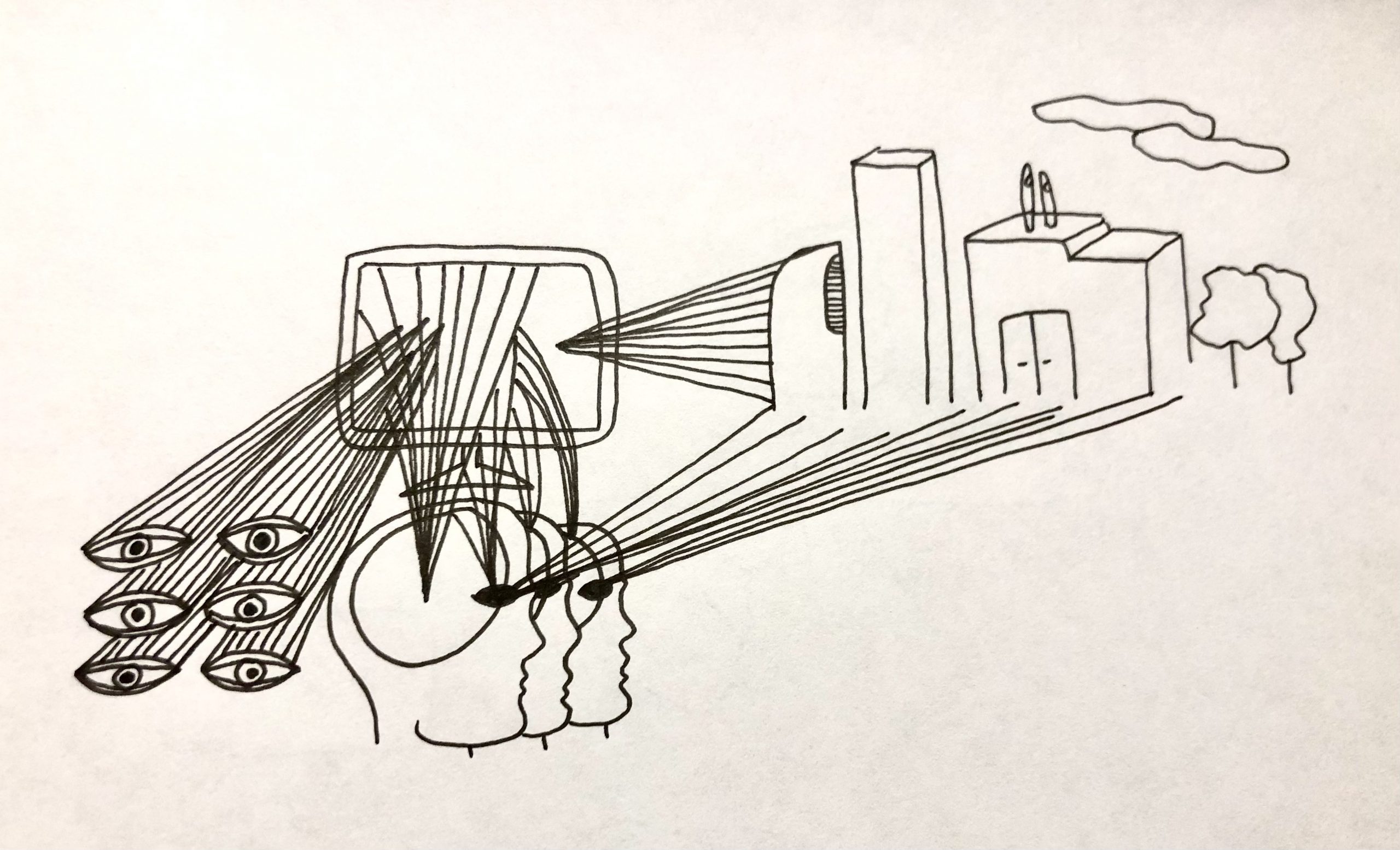

Activity: I created an intentionally subjective diagram for my own visualization of NM. I began by thinking about key actor-participants in my own life, there are millions of course, but for the sake of a legible diagram, I kept it to the first few that came to mind. I thought about people, places, materials, concepts, and landmarks. As I thought about how each were connected to each other, I drew lines representing the relations between the active participants. NM focuses on the relationships between things, as Monforte explains, “not in terms of what it is…but it terms of what it does, that is, in terms of its capacities to act and affect” (p. 380), the rust-coloured relational lines within the diagram are intentionally dominant. Although not central to the diagram, the actors are clearly represented, as without them there would be no relationality. A close-up of the relational lines shows they are not stable but are in constant flux. Each time I consider this diagram I see opportunities to add more, or make edits, for example, the actors are not static either – they are subject to continual change just like their relational connections.

As we continue through this lesson, think about how you begin to construct the concept of NM. Pull inspiration from your learning process, the lesson, dialogue with other learners and your own prior experiences to create a personalized diagram of NM.

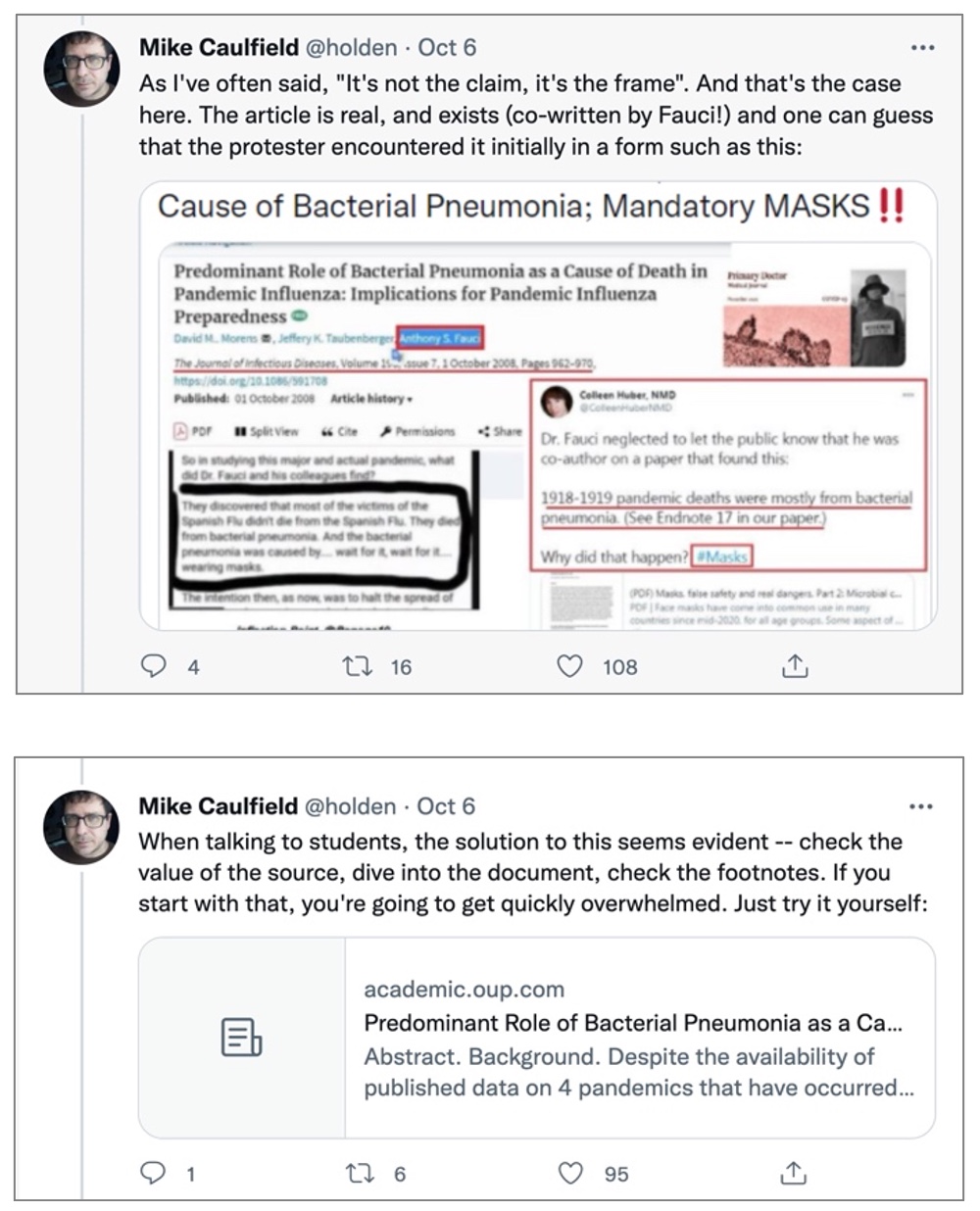

Slide Two: Activate Prior Knowledge by Identifying What New Materialism is Not

NM acknowledges the fluidity of reality, recognizes the impossibility of objectivity, and infers a rich, complex, and dynamic perspective of interconnected relationships. It can be useful to understand NM by clearly defining what it is not. This act can seem limiting, or binary in nature, but think of it like this: NM stands for endless possibilities, it does not include theories or ways of thinking that impose limits or are inherently static or exclusionary.

Many contemporary theories reject the following concepts, (Toohey, 2018, p. 29) which might lead us to question the ‘new’ in new materialism’s name (Monforte explores and questions the new as well in his 2018 article), yet I perceive it as a framework to apply to our overarching perspective of reality – an ontology that runs beside and with theories of gender, feminism, post-structuralism, semiotics, etc. The individual parts might not be new, but to me at least, the collective whole is.

Activity: After each of the following concepts are introduced, I invite you to call out or make notes of examples of these same concepts that you have come across in past readings, classes, or research – your examples can be of theories/ideas that support, reject, or are related to these terms. Of note: Each concept will be introduced with its corresponding diagram.

To expand upon the non-dualist nature of NM, inclusive of all forms of actor-participants, we must also understand that this ontology is not human-centric. The agency usually ascribed to humans is evident in non-human entities in how their design, construction, physicality and use actively shape reality. Toohey (2018) explains that “New materialism… argues that an anthropocentric focus on what humans do, to/with one another, on what their intentions are or on what is done to them ignores important aspects of how the world operates, pointing out that material things also perform: ‘They act, together with other things and forces, to exclude, invite and regulate particular forms of participation’ (Fenwick & Edwards, 2010: 7)” (p. 27).

Mind/body, human/non-human, organic/ inorganic; NM invites us to think beyond the binary, although that might seem obvious, many common binary constructs are foundational to Western constructs of reality, particularly the human/non-human binary, remembering that a core principle of the theory is that all things, or actor-participants in our reality, whether human, conceptual, environmental, synthetic, are considered with equal significance. Toohey (2018) further illustrates, “as well as asserting that human things (minds, bodies) are not separate but entangled with one another, new materialist scholars take the distinction between humans and non-humans to be an important dualism to contest; as anthropologist Ingold (2013: 31) put it, a new materialist perspective ‘returns persons to where they belong, with the continuum of organic life’” (p. 27).

- Hierarchical / Transcendent

Hierarchical systems of power simply do not fit into a networked or “rhizomatic” (Monforte, 2018, p. 384) relational model, which Montfort describes as “[leaving] room for disruption, wonder and dalliance; it unfolds a meaningful space for thought to move in all directions” (p. 384). When considering hierarchies, I am reminded of the structure of Hegel’s dialectic: a system where a thesis opposes an antithesis (binary) to create synthesis, ultimately leading to a new thesis to be challenged by another opposing antithesis ad infinitum (Maybee, 2020), or until eventually the ultimate perfection is reached – a kind of transcendence of knowledge. A rhizomatic system “…moves away from static, transcendent traits of ‘identity’ to a concern for change, reciprocal relations and difference, and underscores ‘the intrinsic indeterminacy and mobility at the heart of any process of becoming’ (de Freitas & Sinclair, 2014: 34)” (Toohey 2018, p. 30).

The Merriam-Webster dictionary includes “the practice of regarding something (such as a presumed human trait) as having innate existence or universal validity rather than as being a social, ideological, or intellectual construct” (Merriam-Webster, n.d.) in its definition of essentialism. Monforte (2018) backs this up, describing essentialism as “…the view that entities have essential attributes and ontological integrity that precede their relations” (p. 380). NM is a relational ontology, meaning that relations, including “social, ideological, or intellectual construct[s],” are integral to understanding reality through this ontology – because of its relational focus, NM rejects essentialist ways of thinking.

Slides Three and Four: Keywords / Key Concepts

James Gee (2007) explains, “by a semiotic domain I mean any set of practices that recruits one or more modalities (e.g., oral or written language, images, equations, symbols, sounds, gestures, graphs, artifacts, etc.) to communicate distinctive types of meanings” (p. 18). It is evident that NM scholars employ a rich set of language specific to their semiotic domain. We will look at some of the keywords currently associated with NM, as gaining an understanding of the meaning of these terms will allow greater access to the more complex aspects of the theory.

Activity: Many of these keywords and concepts have already been touched upon when discussing what NM is not. As in the previous slide, each keyword has a corresponding illustration. As we go through each illustration, learners are invited to guess what word or concept each image might represent. Consider the following questions:

- Regardless of whether you can guess the exact keyword, how do you interpret what the image is trying to convey?

- Can you recognize any symbolism or iconography used?

- Does your own understanding of the keyword lead to a different kind of visualization?

- How might you change, improve, or add to the illustration?

Illustration: like the binary illustration of a circle halved, one side black, one side white, the multiplicities circle is cut into numerous unique parts.

All aspects of NM invite us to think about possibilities. What are the countless relations that form who we are? How can we consider things from multiple perspectives? Rather than being limited to binary or dualist perspectives, we can consider that our place in the world is bound by numerous, equally valuable relations to other humans, spaces, objects, animals, nature, etc. (Toohey, 2018, p.28).

Illustration: a shooting star, which represents the power/action that is not limited to human entities.

Some scholars of NM believe that all actors, whether human or non-human have the capacity to have agency, acting or asserting power that affect other actors relationally connected to them. Others believe that the agency does not lie with the actor themselves, but that it emerges through the relations between actors. (Toohey, 2018, p. 32).

Illustration: a simplified model of my initial NM diagram that shows a tangled mess of relations connecting various actor-participants.

Entanglements refer to the rhizomatic set of relations connecting us, or a particular actor-participant to other actors. The term entanglement allows us to think of the relationships as being complex, in motion, variable and unpredictable. Terms like ‘web’ or ‘network’ aren’t quite sufficient as they infer a geometric, neat, and predictable set of connections, which is not the reality understood through NM.

Illustration: a visual focus on the matter that exists between two points, to depict the importance of the relationships between entities as they tell us more about reality than looking at the entity in isolation.

Returning to Monforte’s (2018) explanation, “this relational ontology leads new materialist scholars to assert that matter is to be studied not in terms of what it is (i.e. essence), but in terms of what it does, that is, in terms of its capacities to act and affect (i.e. agency) (Fox and Alldred 2017) (p. 380).

Illustration: radiating lines that represent a phenomenon experienced by an entity that precedes meaning-making or contextualization, but the experience itself is provocative of such mediation.

Toohey (2018) addresses the work of Massumi to explore affect:

Philosopher Massumi (2002) has brought to our attention the concept of affect, a matter of ‘autonomic responses that are held to occur below the threshold of consciousness and cognition and to be rooted in the body’ (Ley, 2011: 443). Massumi rejected the conflation of affect with emotion, preferring to see affect as independent of meaning or intention and, as some of the research he cited showed, affect occurs before emotion comes to awareness (p. 33).

Illustration: A zoomed-out view of multiple actors engaging in relational action, provoking the evolution, fluctuation, and emergent transformational process of becoming.

Toohey (2018) explains, “new materialism sees people, discourses, practices and things continually in relation, under construction and changing together, becoming different from what they were before” (p. 29). The subtle and poetic term becoming is consistently used by new materialist scholars to describe the ever-changing essence of all things. The term is intentionally vague to avoid implications of an ‘ultimate goal’ or positive/negative outcomes, simply that everything is in flux, and as we are bound by linear time, reality seemingly emerges, or becomes.

Illustration: two actors work collaboratively, creating and merging (or entangling) their unique relational connections with each other, while simultaneously drawing from their own unshared/not-yet-shared agentic connections.

Hill (2017) further explains what is meant by the term intra-action, “Interaction assumes distinct, independent entities that are empowered with agency to act upon one another. Intra-action by contrast, involves the “mutual constitution of entangled agencies” (Barad, 2007, p. 33) where complex material practices assemble in particular ways to produce specific phenomena” (p. 3).

Illustration: visually, a play on scientific diagrams of diffracted light, but in this case, the image represents energy/knowledge/ideas/language being received by an actor-participant and being released diffractively: radiating out in all directions to connect with something (multiple things) in new ways.

As Hill (2017) describes, “diffraction, within the context of physics, involves the bending and spreading of waves when they encounter a barrier or an opening. Diffraction therefore, as a metaphor for inquiry involves attending to difference, to patterns of interference, and the effects of difference making practices. Diffraction creates something ontologically new, breaking out of the cyclical, inductive realm of reflection” (p. 2).

Slide Five: New Materialism in Action

Pre-Activity: Request for learners to have read Brayboy and Maughan’s (2009) “Indigenous Knowledges and the Story of the Bean”. Optional reading: Latour’s (1992) “Where are the missing masses? The sociology of a few mundane artifacts”.

Example One: Indigenous Knowledges and the Story of the Bean

Brayboy and Maughan’s “Indigenous Knowledges and the Story of the Bean” (2009) is a paper that describes a challenging experience that occurred during an intensive program for Indigenous pre-service teachers. The site teacher educators (STEs) of the program initially determined that their pre-service student teachers were not sufficiently capable to begin independently teaching, yet, when one of the pre-service teachers detailed what was lacking in fourth-grade lesson plans from an Indigenous perspective, the opinions of the STEs radically shifted. The initial lesson plans took on a Westernized bias and did not take into consideration or allow room for the Indigenous students’ holistic knowledge systems. Brayboy and Maughan (2009) illustrate the holistic nature of Indigenous Knowledge Systems:

A circular worldview that connects everything and everyone in the world to everything and everyone else, where there is no distinction between the physical and metaphysical and where ancestral knowledge guides contemporary practices and future possibilities, is the premise of many Indigenous Knowledge Systems. This fundamental holistic perspective shapes all other understandings of the world (Fixico, 2003; Marker, 2004 Stoffle, Zedeño, & Halmo, 2001). More specifically, holistic or circular understandings do not draw separations between the body and mind, between humans and other earthly inhabitants, and among generations (p. 13).

Toohey (2018) illustrates that many aspects of NM consciously aim to break down binary and hierarchical constructs of Western thought, but that many non-West ideologies never held these limiting perspectives:

Other religious, cultural and philosophical traditions do not make the same dualistic assumptions found in the Western European tradition… Metis scholar Todd (2016: 5) pointed out that this view has been written and talked about in Indigenous scholarship for some time, and briefly described the writing of Inuk author Qitsualik (1998) about the Western Arctic (Canada) concept of Sila: ‘the breathe [sic] that circulates into and out of every living thing’…Todd argued that understanding that humans, the environment, water, climate, animals, and so on are in relation with one another was characteristic of the thinking of various Indigenous groups. Todd suggested that progress in new materialism (or postmodern ontologies) will mean that we recognise ‘first and foremost, [we are] citizens embedded in dynamic legal orders and systems of relations that require us to work constantly and thoughtfully across the myriad systems of thinking, acting and governance within which we find ourselves enmeshed’ (Todd, 2016: 16) (pp. 26-27).

Optional Example Two: Where are the missing masses? The sociology of a few mundane artifacts

Explore similarities between Latour’s Actor Network Theory and NM and consider how to think of seemingly mundane objects such as a door as complex relational systems through a NM perspective.

Questions:

- What connections do you see between NM and “The Story of the Bean”?

- Do you think NM consciously draws on non-West ideologies, such as Indigenous Knowledge Systems?

- Considering “The Story of the Bean” is it appropriate to call NM “new”?

- Think of any mundane activity you participated in today (e.g., calling a family member, taking a shower, making breakfast, going for a walk with your partner). Consider all the actors connected to you through this simple activity. What is the nature of these relations and are they static or in flux? If you consciously shifted a relation, how would it affect your existing entanglement? What if one of the other actors made a noticeable change? How would it affect you or others in your entanglement?

Concluding Activity: With what you have gleaned from this lesson, how has your personal diagram for NM changed, transformed, or become something new? To document a moment in your fluctuating subjectivity, draw, either by hand, or digitally your visual conception of New Materialism.

References

Brayboy, B. M. J., & Maughan, E. (2009). Indigenous knowledges and the story of the bean. Harvard educational review, 79(1), 1-21

Gee, J. (2007). Semiotic domains: Is playing video games a “waste of time?” In What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy, 17-45. New York: Palgrave and Macmillan.

Hill, C. M. (2017). More-than-reflective practice: Becoming a diffractive practitioner. Teacher Learning and Professional Development, 2(1).

Latour, B. (1992). Where are the missing masses? The sociology of a few mundane artifacts. Shaping technology/building society: Studies in sociotechnical change, 1, 225-258. https://www.open.edu/openlearn/ocw/pluginfile.php/877054/mod_resource/content/3/dd308_1_missing_masses.pdf

Maybee, J. E. (2020, October 2). Hegel’s dialectics. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved November 21, 2021, from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/hegel-dialectics/

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Dictionary by Merriam-Webster: Essentialism. Merriam-Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/essentialism

Monforte, J. (2018). What is new in new materialism for a newcomer?. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 10(3), 378-390.

Toohey, K. (2018). 2. New Materialism and Language Learning. In Learning English at School, 25-44. Multilingual Matters.