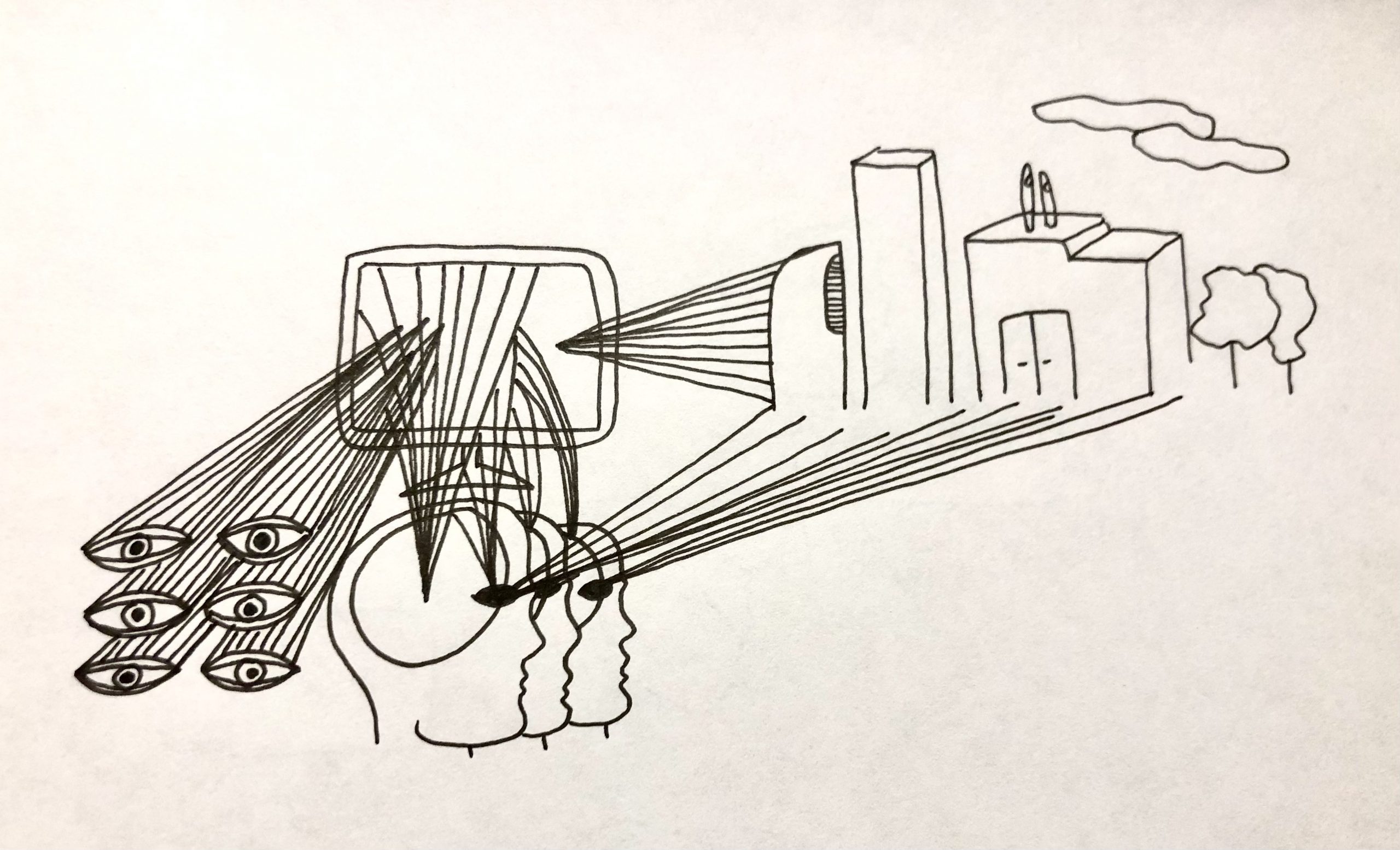

We see and understand the world through the media we interact with and consume. Our perceptions of reality are constructed through the idiosyncratic social and physical environments we are raised and exist within, and form what we understand at varying levels as our culture. Whether the differences are subtle or explicit, each is distinct and it is our varying perspectives and biases that are inherently embedded in the media we create, and the ways we interpret it. Our creation, interaction, perception and critique of media is informed by our culture, and in turn, our culture affects media; an evolving and impressionable ecosystem in continual flux – a media ecology.

Like gravity, Strate’s (1999) definition of media ecology pulls in a variety of interconnected fields of study, “It is technological determinism, hard and soft, and technological evolution. It is media logic, medium theory, mediology. …orality-literacy studies, American cultural studies. It is grammar and rhetoric, semiotics and systems theory, the history and the philosophy of technology. It is the postindustrial and the postmodern, and the preliterate and prehistoric” (as cited in Lum, 2000, p. 1). Lum (2000) interprets this expansive definition as attributing to the “disciplinary multiplicity” (p. 1) of music ecology and identifies “one of the fundamental concerns of media ecology” to be “the defining role that the form and intrinsic biases of communication media play in shaping human communication and, on another level, in the construction, perpetuation and transformation of reality” (pp. 1-2).

Considering media as an ecological system allows us to account for historical context, various cultural perspectives, the inherent fluctuation in meaning and interpretation of media, and numerous biases held by both media and those consuming it; this way of analysing media allows us to see its role as part of a much larger system. Media ecology compels us to question our own perspectives: How does my sociocultural history inform my perception of media? What biases are inherent in the media I consume? How is my reality mediated by the cultures I inhabit, the information communicated through those cultures, and the mediums through which it is consumed? This holistic way of thinking leads us to apply these same questions to others and their multitude of differing histories, biases and contexts.

An education-focused media ecology must view pedagogy and knowledge acquisition with this same holistic perspective. In order to create innovative and engaging educational designs, we need to consider and acknowledge the sociocultural histories of learners, take into account our own inherent biases, and we must ensure that the designs we conceive accurately accommodate and reflect learners’ realities.

For instance, in education, assessment through the medium of written language still prevails, yet when considering the recent evolution of communication-based technologies and their accessibility and pervasiveness in our daily lives, (such as videos on YouTube or TikTok, photography or image curation on Tumblr and Instagram, writing through personal blogs, and on Facebook and Reddit or the creation of audio-based narratives and documentation through podcasting) relying solely on written language represents a narrow view and does not consider the greater educational media ecology. To do this, we must engage new media appropriately: we must consider how learners use media in their lives, both for function and leisure, and reflect this usage through our educational designs. We must employ creativity in our designs, remain flexible and allow for the differences of each learner’s culture, history and opinions to be represented in their work – by doing this we will encourage the construction of inclusive learning environments that cultivate peer learning, potentially developing into active and rich affinity spaces.

References:

Casey Man Kong Lum (2000) Introduction: The intellectual roots of media ecology, New Jersey Journal of Communication, 8:1, 1-7, DOI: 1080/15456870009367375