Part 1

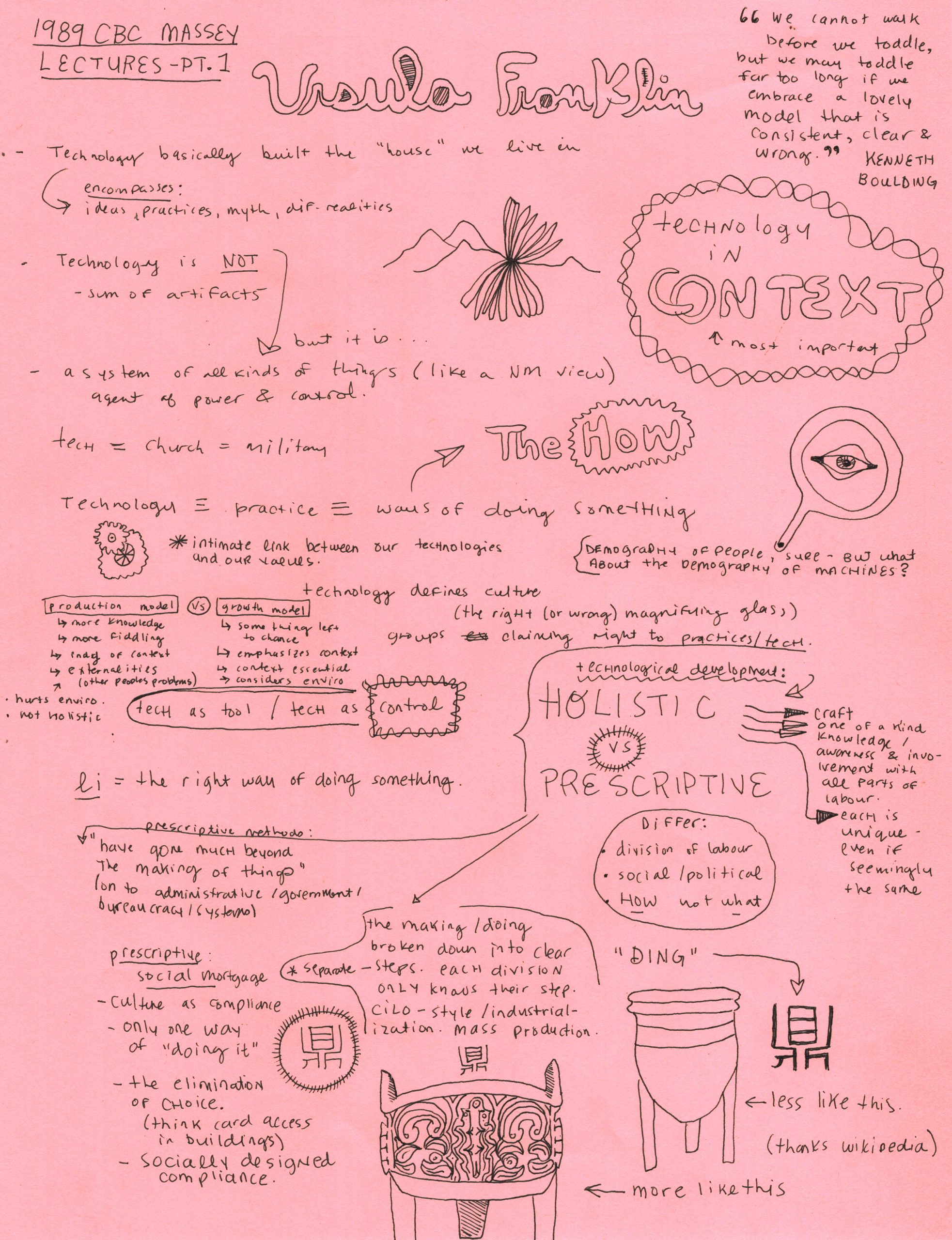

In part one of her 1989 lecture series, The Real World of Technology, and in her book of the same name, Ursula Franklin clarifies that her intention is not to discuss technology as “the sum of artifacts” (1999, p. 21) but rather as part of a greater ecology, “Technology is a system. It entails far more than its individual material components. Technology involves organization, procedures, symbols, new words, equations, and, most of all, a mindset” (p. 21). She suggests that although prescriptive technological systems may allow for efficiency of production, the ultimate cost of abandoning holistic technological developments is a society with built-in systems of power, replacing choice and autonomy, for control through “…in social terms, designs for compliance…” (p. 43).

Based on her ideas of holistic technologies, surely Franklin was aware that her own participation as a critical theorist and generator of technological discourse placed her within a unique entanglement of relations. She states, “I myself am overawed by the way in which technology has acted to reorder and restructure social relations, not only affecting the relations between social groups, but also the relations between nations and individuals, and between all of us and our environment” (p. 22). This statement reflects holistic means of understanding, which is reminiscent of how Miller (1989) describes Lewis Mumford’s inclination toward “holism” that he in turn gleaned from Patrick Geddes, “that no living organism could be understood except in terms of the total environment in which it functioned” (as cited in Strate & Lum, 2000, p. 68). The notion of “holism” shared by Geddes, Mumford, Franklin, and others continues forth and is essential in understanding the emerging New Materialist perspective, as Monforte (2018) illustrates, “the research conducted under the rubric ‘NM’ would not focus on discursive statements nor individual bodies, but rather on actor-networks, entanglements or assemblages of relations between bodies, things, ideas and social formations that affect each other” (p. 380).

Although we can see the benefits of engaging holistic perspectives, the long-standing call for holism is overshadowed by the pervasiveness of prescriptive technologies which Franklin explains is when, “…the making or doing of something is broken down into clearly identifiable steps. Each step is carried out by a separate worker, or group of workers, who need to be familiar only with the skills of performing that one step” (1999, p. 28). We see this in education, particularly in the subjects of math or science, where learners are taught complex abstract ideas, without examples or methods that place the ideas in a greater context or apply them to real-world activity. I am reminded of learning about parabolas while concurrently learning how to use a TI-85 graphing calculator in a high school math class. I can recall the symmetrical arc of the parabolic shape, but the relevancy of the concept and the reasons for learning how to use the graphing calculator remain unknown well into adulthood. This uninspired learning experience was not an example of what Ito et al (2015) call “connected learning,” they explain, “in contrast to more fleeting or institutionally driven forms of learning, connected learning experiences are tied to deeply felt interests, bonds, passions and affinities and are as a consequence both highly engaging and personally transformative” (p. 14). Connected learning allows for an ecological approach to education that not only considers the subject matter as a set of connected relations, but also utilizes a holistic model to actively merge the learner and their previously gained connections into the entanglement.

Part 2

I often listen to podcasts, the radio or television shows while drawing or crafting, so I initially listened to the CBC’s recording of Ursula Franklin’s lecture while working on a weaving. Yet this lecture is traditional in format and exists as a reading of academic text rather than a narrative, open dialogue, or an improvisation. As part one of the lecture series concluded, I realized that although I retained a vague sense of what was said, much of the detail was lost.

I learned recently that I cannot visualize images in my mind. In fact, I was astounded to learn that people do visualize images, as I always thought the instruction “close your eyes and visualize…” was metaphorical. I can recall visual memories by conceptualizing them, but I cannot re-create their image in my mind’s eye. I often wonder if the lack of visual memory has strengthened the emotive, somatic, or olfactory sensations I connect to memory. The condition of not being able to visualize is called aphantasia. The co-worker who accidentally diagnosed my condition told me that she heard it was common for artists and creative people to have aphantasia, that perhaps it is what leads them to create outward representations of their inner thoughts. I re-listened to Ursula Franklin, this time with more focus, and a pen and paper to make notes and illustrations, and to literally draw connections between ideas. After, when I skimmed Franklin’s subsequent book, The Real World of Technology, I was both relieved and disappointed to see that the written word of the text was very closely aligned with the spoken word of the lecture recording – relieved that I could more closely examine Franklin’s ideas, disappointed that rather than being complementary to the lectures, much of the book appeared to be a replication presented in a different medium.

I read Illich and Sanders (1989) chapter “Memory” closely, multiple times and still struggle to understand the statement “Only after it had become possible to fix the flow of speech in phonetic transcription did the idea emerge that knowledge—information—could be held in the mind as a store” (p. 24). Initially this seems impossible – surely some form of memory, though not in the way we understand memory today, must have existed. People must have recognized; this is where I sleep, or this is what I eat because they previously did those things and remember doing them. Illich and Sanders go on to describe the work of Milman Parry whose research clarified that, “a purely oral tradition knows no division between recollecting and doing” (p. 24). Considering this statement, it must be the division that is the key to comprehending thought prior to memory – recollection occurred before the invention of the written language, but it had not evolved into the technology we now take for granted: memory.

Further in the text, Illich and Sanders describe another early technology, a mnemonic technique for storing information for future recitation called a memory palace (pp. 35-36). As the technique instructs a person “to imprint on his memory the interior of a building, preferably a spacious one, visualizing each location—stores, attics, stairs…The person then equates the ideas to be remembered with certain images…” (p. 36) it is obvious, that my inability to visualize has prevented me from expertly employing this elaborate system. It’s not that it’sbut the mental work is slow and headache inducing; I would have to first create a material representation of the space for it to make a lasting impression in my memory. I do not perceive my inability to visualize and maintain a memory palace as an encumbrance – perhaps my verbal communication is more closely tied to my truth, rather than mediated through text, allowing my words to “bubble and flow, not be locked up in script” (Illich and Sanders, 1989, p. 33).

References

Franklin, U. (1999). The real world of technology. House of Anansi. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ubc/detail.action?docID=771808

Illich, I., & Sanders, B. (1989). ABC: The alphabetization of the popular mind. Vintage Books.

Ito, M., Soep, E., Kligler-Vilenchik, N., Shresthova, S., Gamber-Thompson, L., & Zimmerman, A. (2015). Learning connected civics: Narratives, practices, infrastructures. Curriculum Inquiry, 45(1), 10-29. doi:10.1080/03626784.2014.995063

Monforte, J. (2018). What is new in new materialism for a newcomer?. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 10(3), 378-390.

Strate, L., & Lum, C. M. K. (2000). Lewis Mumford and the ecology of technics. Atlantic Journal of Communication, 8(1), 56-78.

Very well done! I worked closely with Ursula Martius Franklin at the University of Toronto in the 1980th and pride myself to know (and share) her thoughts about the role technology plays in our modern world. I am happy to see that her work is not forgotten, and that her ideas are rendered well in this contribution.