Cuisine in Japan is more than a simple means of subsistence but the result of cultural practices molded by Japanese landscapes. Japan’s geography and local, situated between the Sea of Japan (West), the Northern Pacific Ocean (East), the Sea of Okhotsk (North), and the East China Sea (South), and the vast abundance of deep waters in some ways influenced the commodification of fish and other ‘sea’ foods. However, can the geographic situations of an ‘ocean city’ be the sole agent at work in molding high cuisines.

The advent of Japanese cuisine seems a natural response to the rigid geographic conditions presented, however, it was also through radical cultural practices and events that have allowed such patterns of subsistence to endure over time. The Tokugawa Era was very much a radical epoch in Japanese history where many distinctive characteristics of modern Japanese culture were incubated, namely the introduction of Japanese cuisine. In some respects, the prominence of Japanese cuisine has transcended its own cultural boundaries and has spread into those of neighbouring coastal cities ie. Vancouver.

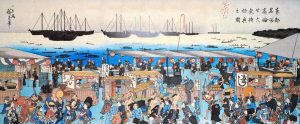

The geographic expanse of the Kanto Region is home to a globally recognized signature or staple of Japanese cuisine, Nigiri-zushi. Tokyo’s well known historic Tsukiji Market adjacent Tokyo Bay, is considered a major agent in the commodification of seafood in the area. However, the introduction of Nigiri-zushi was within the surrounding historic urban streetscapes of Tokugawa Edo. Its praised originator Hanaya Yohei, a radical chef in the city, began selling Nigiri-zushi from street carts and stalls, due in part to the demand of what must have been a lively and bustling Edo streetscape, and lack of refrigeration or cold box.

Although Tokyo’s Tsukiji has been known for its absurd market price for Tuna and other seafood, and an epicentre of culture and commodity, similar instances of culture and commodity developed in the Kansai Region. Setsubun, a Japanese event taking place every spring season in February, illustrates the very infusion of seafood and culture within Japanese landscapes. Eho Maki, a staple of Setsubun festivities, is a sushi roll symbolically thought to bring good omens to residences. Each individual ingredient within the roll acts as an element or part of a good omen. Eho Maki has historically been known to be heavily present within the Kansai region of Japan, where Kyoto, Osaka, Hyogo, and other large cities are situated.

These two areas, the Kansai and Kanto Regions, are apart of the central portion of Japan, with most of its coastal regions within the Omote Nihon. As noted in the previous post, this area is also the location of major transportation infrastructures, events centres, and dense urban epicentres, illustrating further the importance of these landscapes (or regions) in molding Japanese resources, cultures, and subsistence practices over centuries.

Sources:

https://kotaku.com/the-inventor-of-sushi-1683686290

https://www.thespruce.com/good-fortune-sushi-rolls-2031612

https://allabout-japan.com/en/article/920/

https://allabout-japan.com/en/article/4881/

P.P. Karan. (2005). Japan in the 21st Century: Environment, Economy and Society. Lexington, The University Press of Kentucky.