For centuries, Onsens developed as a popular and culturally significant activity made possible by Japan’s active natural landscape (ie. underlying volcanic areas). Admired for its healing properties, hot spring bathing locations began to emerge increasingly during the Tokugawa and Meiji Period in Japan. Many Japanese understand Onsen to be a place of healing, a space that presents remedies for various types of ailments. However, the ever growing popularity of Onsen in Japan has also brought concern as the increasing numbers of Onsen diminish the overall quality of Onsens (recycling waters, contamination, over-chlorination, etc.).

Since the collapse of the economic bubble, the frequency and longevity of Onsen visits, mainly Japanese citizens, has diminished greatly. Due in part to policies undermining the value of Onsens as places of healing and well being, many visitors are now tourists with a smaller amount being Japanese. Nonetheless, it has remained a unique identifier of Japanese culture globally. Moreover, Onsens are seen not only as a way to clean the body, but also the soul. Japan’s Shinto practitioners understood it to be a way to purify oneself with water. It was customary for many to wake up early and purify the body and soul by bathing in an Onsen.

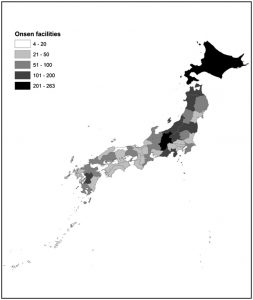

Although it may be difficult to pinpoint geographically a particular area where Onsens first appeared most popular in Japan, mainly due to the sheer abundance of hot springs in every Japanese region, it is nonetheless intriguing to consider the unifying characteristics of such a natural phenomenon. It has also become a way to unify the various geographic expanses of Japan holistically, where each region becomes recognized for its particular Onsens, which in themselves vary greatly. Rather than Japan as having secluded regions of Onsens, Japan is a nation of Onsens; a significant cultural and spiritual activity practiced by all Japanese equally.

Sources:

https://www.nippon.com/en/views/b04702/

Serbulea, Mihaela; Payyappallimana, Unnikrishnan (2012) Onsen (hot springs) in Japan—Transforming terrain into healing landscapes. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/science/article/pii/S135382921200127X?_rdoc=1&_fmt=high&_origin=gateway&_docanchor=&md5=b8429449ccfc9c30159a5f9aeaa92ffb