Over the past 3 ½ months, this course has explored the changing needs and subsequent products of communication through writing and text. One of our first tasks was to produce our personal definitions of ‘text’ and ‘technology’. My definition of ‘text’ was very similar to what the Oxford English Dictionary (n.d.) states as “The wording of anything written or printed; the structure formed by the words in their order; the very words, phrases, and sentences as written.”, essentially, taking oral and spoken ideas and converting them to a concrete and static form that can be referenced at a later date. When I think of ‘technology’ however, my definition differs somewhat from the Oxford Dictionary. Previous to this course, I thought of technology in terms of applying current ideas and knowledge to produce the means to further expand those ideas and knowledge, but for the purposes of this article, I will also incorporate the Oxford Dictionary’s definition of “The systematic treatment of grammar. (Obsolete. rare.)”. My intent with this article is to apply these ideas to western musical notation as text and discuss the history of written music and connect it to the original theme of the course, the reciprocal connections between communication needs, practice and invention with some speculation as to the future directions of musical communications.

What is music?

Music as defined by the Oxford English Dictionary is “The art or science of combining vocal or instrumental sounds to produce beauty of form, harmony, melody, rhythm, expressive content, etc.”. Music is a form of communication and language just as speech is. Various emotions and stories can be expressed with a combination of different tempos, volumes, tone combinations (chords) and note lengths. “Like speech, music has an acoustic code for expressing emotion, and even if a piece of music is unfamiliar, we can “decode” its message.” (Interlude, 2021). We associate and attribute certain vocalizations in speech to certain meanings and do the same with musical intonations. Cross and Woodruff (2009) expand the communicative aspects of music beyond emotional functions and discuss the cultural significance of music in managing social relationships. “…although many of the uses of music will indeed impinge on the affective states of those engaged with it, music fulfils a wide range of functions in different societies, in entertainment, ritual, healing and in the maintenance of social and natural order” (Cross and Woodruff, 2009). Kofi Agawu discusses the functional elements of traditional African music and its connection to language, “While transcending language, however, music nevertheless remains dependent on it; it remains a supplement to language just as language remains a supplement to music.” (Agawu, 2001). Music is used as a means to help memorize and communicate information adding a multimodal element to oral transmission. With music having such a strong functional purpose, the necessity for a reliable, concrete recording system to preserve the format and integrity of certain musical messages becomes evident.

As with many spoken languages, musical intonations can be transcribed to a textual form which we know as musical notation, and just as there are different languages, there are different forms of musical notation depending upon the genre of music, instrumentation, or purpose. In order to transcribe music to a written form that can be interpreted by others, there are certain elements that need to be translated to a textual form including pitch/melody, rhythm, and dynamics. The standard notation on 5 line musical staves is the most common for western classical music. While the purpose of this assignment is not to teach music theory, for the sake of providing context I will attempt to briefly summarize the basics of current western music notation.

In western music, there are 12 musical notes or ‘pitches’ that are represented by the letters A – G. The basic 8 note scale was described with the song ‘Do-Re-Mi’ in the 1964 movie ‘Mary Poppins’.

“Do-Re-Mi” – THE SOUND OF MUSIC (1965) – YouTube

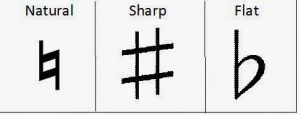

Additional pitches are indicated by adding symbols to the letters that either raise the pitch or lower it.

Figure 1 Accidentals (taken from What are accidentals in music? – Quora)

The pitch is indicated by its place on a ‘stave’ of 5 lines.

Figure 2 The stave and pitches (taken from The Stave or Staff | Hello Music Theory)

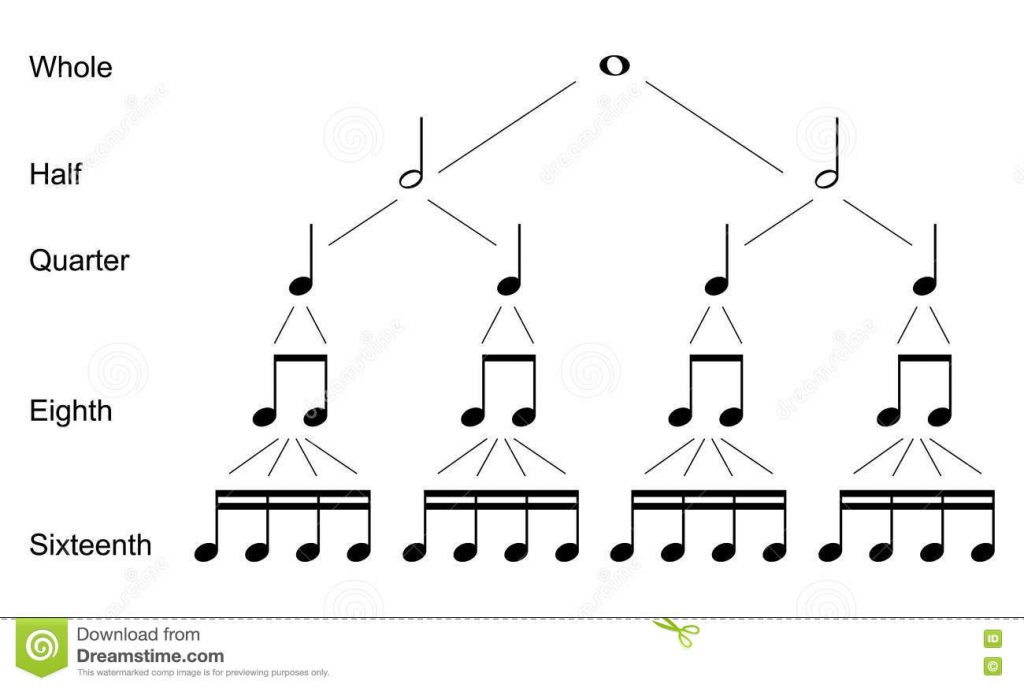

Pitch length is represented by a filled in or hollow oval with the addition of lines and ‘flags’. A ‘whole’ note is the longest value and the note lengths are divided fractionally from there.

Figure 3 – Note lengths (taken from Types of musical notes stock illustration. Illustration of harmony – 73676989 (dreamstime.com))

Musical compositions are also segmented into ‘bars’ or ‘measures’ which have a certain value of ‘beats’ which defines the ‘rhythm’. The ‘time’ signature determines how many beats per measure.

Figure 4 – Time Signature (taken from https://www.blendspace.com/lessons/KaLkWJR8HpBZgg/meter-signatures-are-also-known-as-time-signatures)

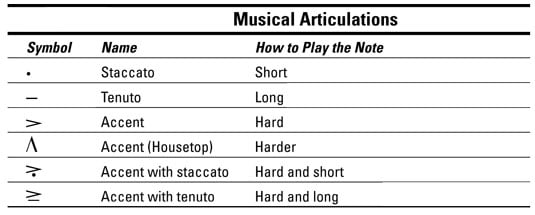

Lastly, dynamics, tempo and articulations are indicated by a variety of symbols that attempt to convey the composer’s intended effects to the musician.

Figure 5 – Dynamics (taken from Dynamics in Music (thinglink.com))

Figure 6 – Music Tempos (taken from Tempo – Music Theory Academy)

Figure 7 – Musical Articulations (taken from https://www.dummies.com/article/academics-the-arts/music/instruments/piano/how-to-articulate-your-piano-playing-191585)

Even with this wide array of characters and notation options available, each musician will interpret the score differently, and the product may differ from the composer’s vision. “People believe that music is not a stationary object but a fluid performing art which does not produce two exactly identical performances (except for replicated electronic sounds).” (Park, 2017). This to my mind, is no different than written stories that are read with personal interpretations and inflections each time they are shared, influenced by the amount of specific detail written, and the background and cultural biases of the reader. “It is generally accepted that the human performer will add considerably to the music, or ‘fill it with life’ through the process of interpretation, as if impregnating the music with the life that got extinguished when it was written down in notational form.” (Magnusson, 2014).

The History of Musical Notation

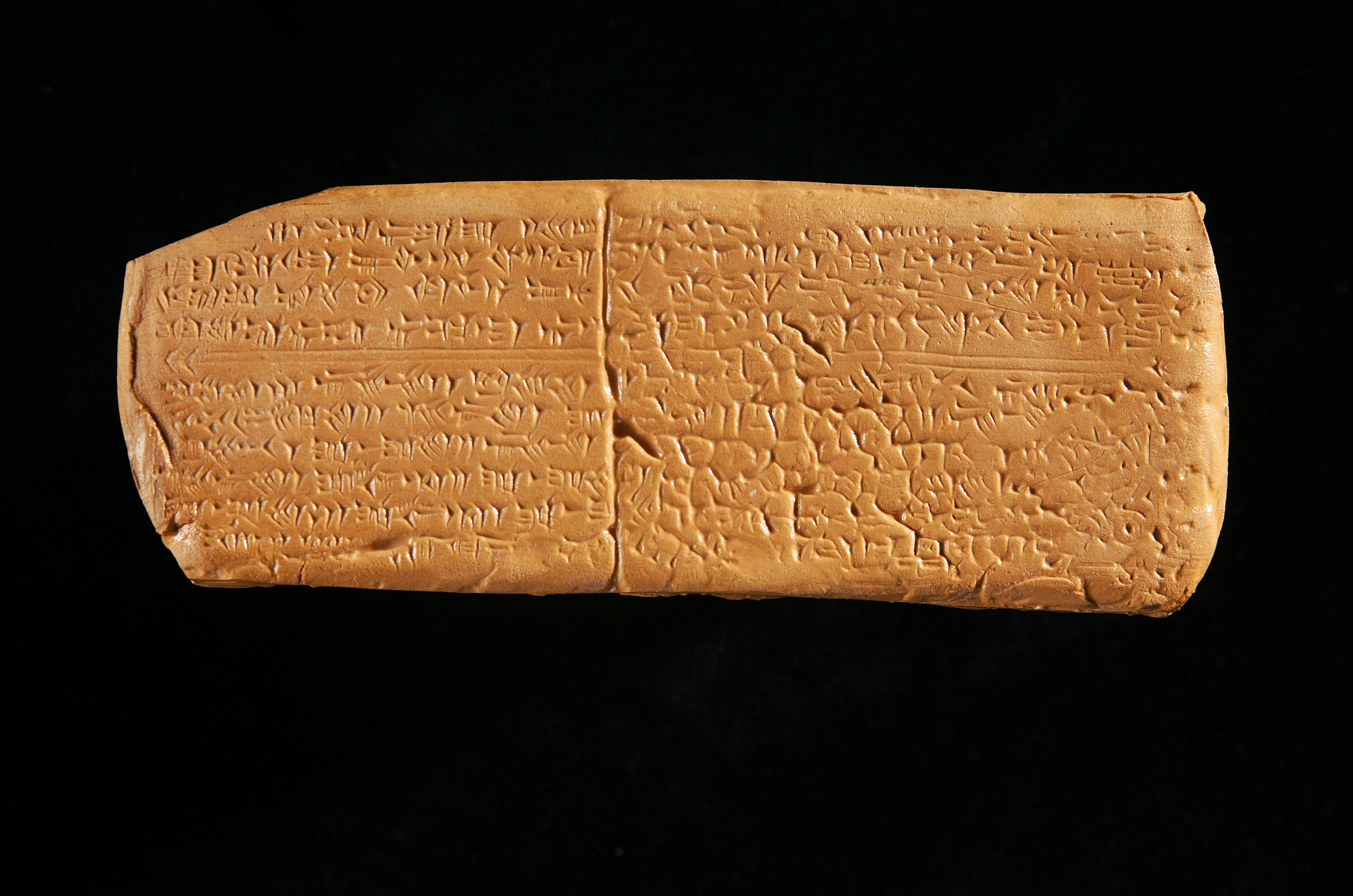

The very earliest example of basic musical notation was found on a cuneiform tablet in modern day Syria dating around 3400 years old and consists of musical instructions, interval names and number signs. (Davis, 2021 Wikimedia Foundation, 2020) “The notation was verbal in form and not a graphical representation. The seven pitches described in the text used the same intervals that make up our modern major scale (the diatonic scale) and could be played on a seven-string lyre.” (Gaare, 1997)

Figure 8 – Hurrian Hymn (taken from Listen to the enchanting sound of the world’s oldest song, the Hurrian Hymn (classicfm.com))

Legend credits the birth of musical theory in 600 BC to Pythagorus (Stewart 2017, Sanders 2016, Williams, n.d.) who allegedly walked by a blacksmith’s shop, noticed the different tones that came from the different sized hammers, and was inspired to determine the mathematical ratios and relationships between tones produced from plucked strings and their lengths. He observed and calculated the sound wave frequency ratios and the corresponding intervals between them, the most notable being the 2:1 ratio which we know as the ‘octave’ which is when one tone frequency is doubled. “ This 2:1 ratio is so elemental to what humans consider to be music, that the octave is the basis of all musical systems that have been documented – despite the diversity of musical cultures around the world.” (Sanders, 2016) This is the basis for our 8 note scale today.

The oldest known complete surviving musical composition with lyrics and notes is the ‘Seikilos Epitaph’ found on a tombstone in Turkey in 1883. (Williams, n.d. Hall & Hall, 2021). Dating back to around 100 – 200 BC, the Ancient Greeks took the 8 notes of Pythagorus’ scale and labelled them with letters from the Greek alphabet.

Song of Seikilos – 1st century Greek song – YouTube

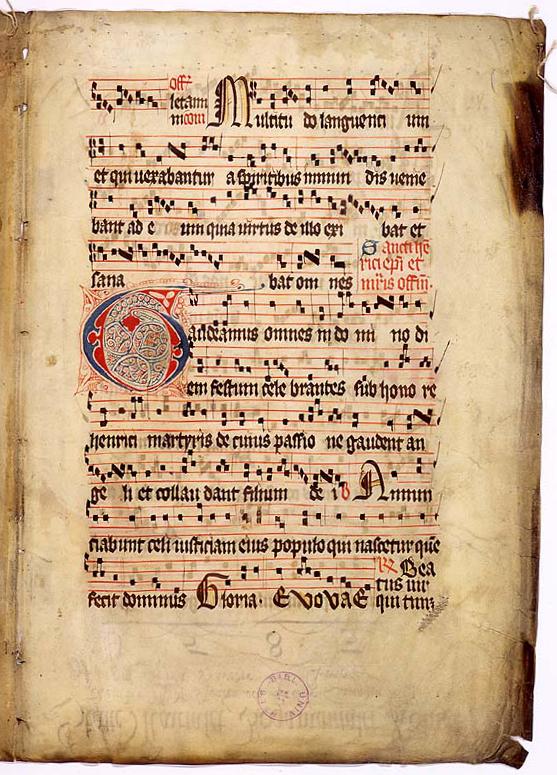

Around 600 AD, a Monk’s training included memorizing copious religious songs known as ‘Plainchant’. The volume of songs to memorize was becoming unmanageable, so a sorting and categorizing system called ‘neumes’ was developed. (Williams, n.d.). This was a system of symbols written over text that indicated where the pitch would rise and fall, and were designed to be more of a ‘cheat sheet’ per se, reminding the singer of a tune that they were already familiar with. (The Optical Neume Recognition Project).

Figure 9 – Gregorian Chant Neumes (taken from How Was Musical Notation Invented? A Brief History | How To Classical | WQXR)

Although an improvement, this system still proved insufficient for young monks struggling to learn all the chants, so around 1025 AD, a Benedictine monk by the name of Guido d’Arezzo is credited with developing (among other things) a 4 line system (staff) with letters that allowed the neumes to be placed on the lines and spaces, thus providing a frame of reference for the chanters to determine pitches. “Prior to Guido’s invention, music notation was sparse and unclear. Serving only as a reminder of a previously learned melody, the musical notation of the early medieval period provided little help to a singer who was studying a chant for the first time…In addition to placing the lines of the staff a third apart, Guido added colors and clef signs to indicate the specific pitch of the lines and “to show where the following neume is to be placed.”” (Reisenweaver, 2012).

Figure 10 – First staff (taken from How Was Musical Notation Invented? A Brief History | How To Classical | WQXR)

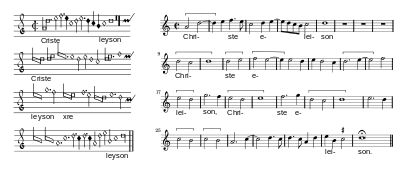

Guido’s system was refined and modified in the following years adding extra lines and colors and ultimately the neumes were replaced with square shaped note symbols. (Williams, n.d.) There was one missing element however, there was no way to determine the length of time a note should be held.

Mensural notation (or ‘measured music’), being able to represent both pitch and rhythm, was developed around 1300 AD. In this system (which is very similar to current day notation), different shapes were given to the notes to indicate their relative length to each other.

Figure 11 – Mensural Notation compared to current notation (taken from Mensural notation – Wikipedia)

From this point on, compositions became increasingly complex, adding notations for changes in dynamics, articulations, and more complex time signatures and key signatures allowing composers to express themselves with a more explicit and detailed musical score resulting in the notation we use today.

What is the future of musical composition?

As with any technological advancements, innovations and advances are driven by need. Just as the need to record and preserve musical compositions let to the developments of increasingly complex and detailed musical notations, there will be more developments that will allow for composers to communicate their musical intentions more creatively and completely. That being said, musicians will also need room for personal interpretations, allowing for the ‘human/variable’ element in musical performances.

Advances in digital music production and artificial intelligence have pushed the boundaries and capabilities of musical composition and notation. One can download musical applications for their personal digital devices and compose music without having much theoretical knowledge as the trend is for music to be directly recorded rather than written down and notated. Hope (2019) describes music that is no longer notated, but rather graphic ‘animated notation’ that uses “…imagery not related to traditional music notation… It can shift the emphasis of music composition towards texture and dynamics over harmony and melody and provide a wider range of choices for performers…” (Hope, 2019). Thus, it seems that musical notation has come full circle, from being translated onto paper, the development of a system to communicate a creative expression for others to emulate, to personal expression/composition digitally without the need for concrete, textual transcription. Music is constantly undergoing its own evolution/transition just as any other language.

References:

Agawu, V. Kofi (Victor Kofi). (2001). African music as text. Research in African Literatures, 32(2), 8-16. https://doi.org/10.1353/ral.2001.0037

Cross, I., & Woodruff, G. (2009-04-23). Music as a communicative medium. In The Prehistory of Language. : Oxford University Press. Retrieved 7 Dec. 2021, from https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199545872.001.0001/acprof-9780199545872-chapter-5.

Davis, L. (2021, April 3). Listen to the enchanting sound of the world’s oldest song, the Hurrian hymn. Classic FM. Retrieved December 8, 2021, from https://www.classicfm.com/music-news/videos/oldest-song-melody/.

Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. (n.d.). Guido d’arezzo. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved December 8, 2021, from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Guido-dArezzo-Italian-musician.

Gaare, M. (1997). Alternatives to Traditional Notation. Music Educators Journal, 83(5), 17–23. https://doi.org/10.2307/3399003

Haines, J. (2008). The origins of the musical staff. The Musical Quarterly, 91(3-4), 327-378. https://doi.org/10.1093/musqtl/gdp002

Hall, S., & Hall, S. A. (2021, November 4). Engraved on a tombstone almost 2000 years ago, this is Music’s oldest surviving composition. Classic FM. Retrieved December 8, 2021, from https://www.classicfm.com/discover-music/seikilos-epitaph-oldest-surviving-composition/.

How was musical notation invented? A brief history: How to classical. WQXR. (n.d.). Retrieved December 8, 2021, from https://www.wqxr.org/story/how-was-musical-notation-invented-brief-history/.

Hope, C. (2019, July 19). Animated notation means music’s on the move – literally. Monash Lens. Retrieved December 8, 2021, from https://lens.monash.edu/@politics-society/2019/07/19/1375851/the-future-of-music-notation-in-a-digital-world.

Interlude. (2021, April 13). How do musicians communicate while performing? Interlude. Retrieved December 7, 2021, from https://interlude.hk/communication/.

Magnusson, T. (2014). Scoring with code: Composing with algorithmic notation. Organised Sound : An International Journal of Music Technology, 19(3), 268-275. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355771814000259

Stewart, J. (2017, August 2). Timeline 002: Pythagoras and the connection between music and math. Vermont Public Radio. Retrieved December 8, 2021, from https://www.vpr.org/vpr-classical/2015-05-04/timeline-002-pythagoras-and-the-connection-between-music-and-math.

The Optical Neume Recognition Project a tool to investigate early staff-less music notation. The Optical Neume Recognition Project. (n.d.). Retrieved December 8, 2021, from https://www.cs.bham.ac.uk/~aps/research/projects/neumes/neumes.php.

Magnusson, T. (2014). Scoring with code: Composing with algorithmic notation. Organised Sound : An International Journal of Music Technology, 19(3), 268-275. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355771814000259

Music 101: What is musical notation? learn about the different types of musical notes and time signatures – 2021. MasterClass. (n.d.). Retrieved December 7, 2021, from https://www.masterclass.com/articles/music-101-what-is-musical-notation-learn-about-the-different-types-of-musical-notes-and-time-signatures#what-is-musical-notation.

Oxford English Dictionary. (n.d.). Retrieved December 7, 2021, from Home : Oxford English Dictionary (ubc.ca)

Park, S.J. (2017). Sound and Notation: Comparative Study on Musical Ontology. Dao, 16, 417-430.

Reisenweaver, A., & Cedarville University. (2012). Guido of arezzo and his influence on music learning. Musical Offerings, 3(1), 37-59. https://doi.org/10.15385/jmo.2012.3.1.4

Sanders, E. (2016, July 4). Music and mathematics: A Pythagorean perspective. University of New York in Prague. Retrieved December 8, 2021, from https://www.unyp.cz/news/music-and-mathematics-pythagorean-perspective.

Wikimedia Foundation. (2020, December 3). Hurrian songs. Wikipedia. Retrieved December 8, 2021, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hurrian_songs.

Williams, V. (n.d.). Notation: The evolution of music notation. mymusictheory.com. Retrieved December 8, 2021, from https://www.mymusictheory.com/reference/345-the-evolution-of-music-notation.