Speculative Futures

This week’s task was to create two speculative narratives on our potential relationship with media, education, text and technology in the next 30 years, and I’ve fictionalized myself for both narratives.

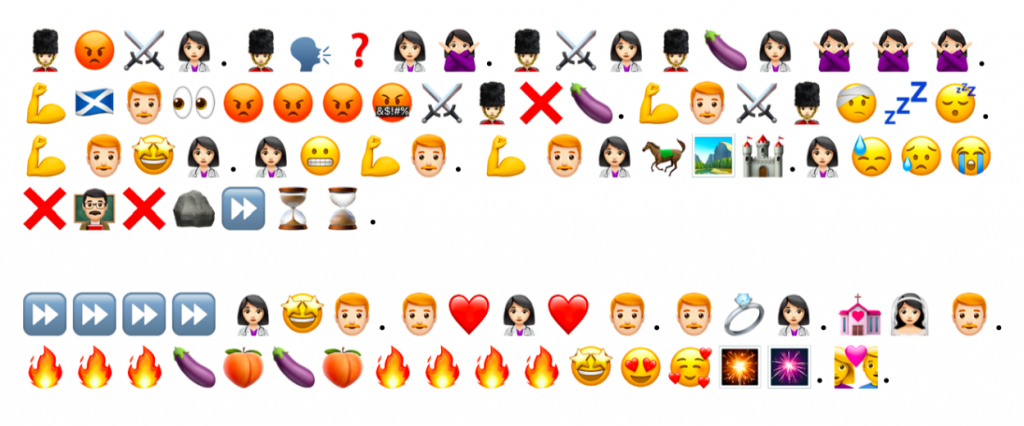

The first narrative is an interactive vignette about brain/computer interfaces in Inklewriter and the second is a chat story created with the TextingStory app on iPhone – the upload exceeded the 20mb file size for WordPress, so I’ve hosted it here.

Speculative Genres

My introduction to speculative design and fiction was through Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake trilogy, mentioned by Dunne & Raby (2013) as not only a masterful example of speculative literature but a provocation of ideas surrounding “social, cultural, and ethical implications of science and technology.” What makes the trilogy speculative instead of sci-fi is that everything in the post-apocalyptic world Atwood designs could have technically existed within the possibilities of 2003 and beyond’s technology and science. If you think lab-grown but non-animal protein Beyond Meat or an Impossible Burger is disgusting, how do you feel about lab-grown chicken? But only the edible parts of a chicken – like the breasts – without the rest of the chicken, or at least without the unnecessary parts? If you want to read for yourself, check out the book, or read this blog site’s excerpt from Oryx and Crake regarding the chicken, or ChickieNobs. There’s a nod to this in the first narrative.

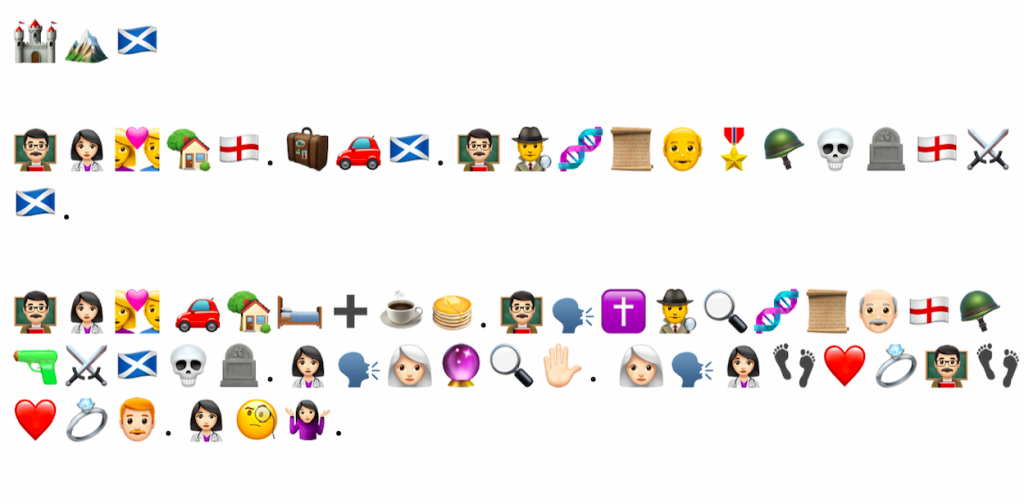

My narratives take inspiration from coursework in ETEC 522 and ETEC 523 and my exploration of exciting emerging technologies such as chatbots (Alex in the second narrative is an AI chatbot), VR/AR and immersive experiences, the upcoming 5G revolution and its impact on Internet of Things and device connectivity, the potential of posthumanistic brain/computer interface technology via neuralnanobot implants. I’ve also been inspired by the 2020 dystopian adolescent fiction novel Feed by M.T. Anderson, where the feed is a brain/computer interface in a society driven by consumerism and corporate interests (sound familiar?) and the Netflix show Upload where the less resourced 2 gigs run out of data and exist on pause until the next month’s data recharge.

The first narrative also touches briefly upon the issues of the quantified self and our desire to learn more about ourselves and the world in quantitative ways: whether it’s through DNA testing, FitBit or Apple Watch daily steps tracking, social media and app use to check into locations, keeping up with our likes/faves and streaks, maintain a record of the beers we’ve imbibed or birds we’ve seen, we are chasing our quest for knowledge, our goals, our self-esteem and happiness using digital technologies. Admittedly, I engage in some of the above mentioned forms of tracking and measure my quantified self through social media and app use, and I have an understanding of some of the risks in sharing my personal data for the enjoyment I receive in return. Rutsky (2018) explains the draw and risks:

The attraction of these technologies lies precisely in their promise to allow users to be free, active creators and producers. Yet, this promise of increased freedom, creative expression, and mastery is premised upon converting virtually every aspect of life, nature, and culture into quantitative terms, into data – including human life.

As the world becomes more digitized and technologically advanced, some of the speculative futures imagined by revered thinkers such as Kurzweil, Orwell, Atwood, Anderson, Huxley, and even Musk have or will become a reality instead of science fiction, and one thing is certain: our lives have become inextricably linked with technology. And we are either unwilling or unable to remove ourselves from it completely. When I began the MET program I was much more of a tech Pollyanna and bought into the idea of techno-utopianism much more than I do now. I personally find it impossible to rid myself of everyday technologies I know might be harmful or exploitative from a personal and collective data point of view, and I think we have all had to embrace technology in ways that have expanded our comfort zones to remain relevant, either culturally, socially, or economically. Dunne & Raby (2013) and countless others have cautioned against wholeheartedly accepting technology for all its promise and possibilities without a consistent and vigilant critique of it – and ourselves. Technology is not a runaway train or autonomous being. We have created it, and we must act ethically and reflectively in our creation and use of it.

References

Dunne, A., & Raby, F. (2013). Speculative everything: Design, fiction, and social dreaming. MIT Press.

Rutsky, R. L. (2018). Technological and posthuman zones. Genealogy of the Posthuman. https://criticalposthumanism.net/technological-and-posthuman-zones/

I started gardening when I move to Toronto which is a little bit Ironic considering that there’s a lot more land to Garden on in Texas but when I live there I live in Austin with roommates in apartments and really didn’t have my own space where I can grow things I declared myself to have a green thumb because I would kill any indoor plant that was given to me or that I purchased So eventually I just stopped buying them one of the things that it’s funny about growing plants indoors is that everybody over Waters them constantly and that’s what causes their death death by love and overwatering that first year in Toronto I grew tomatoes peppers basil planted some flowers like Marigold and has some peas growing up a trellis in the backyard we didn’t have much space and I had to lay down some cardboard and build a raised bed to make it happen but eventually the second year I used up a lot more space by making more red raised beds I really got into gardening do when we moved from Toronto to Niagara so I can go to school in the greenhouse technician program that’s when they really took off a lot of methods and the science behind growing and so that’s giving me the confidence to do what I do at my own home I’m really into native gardening as well as vegetable gardening and I really like growing weird vegetables but then sometimes it takes an effort to figure out what to do with them in the kitchen but my interest in gardening kind of stems from my interest in eating food and then learning how to cook food I like to eat at home as opposed to going out all the time now the focus has shifted a bit from gardening just for vegetables and herbs to planting a lot more native plants to attract pollinators and birds to the garden I really enjoyed this winter watching all of the birds come to the yard and eat from the feeders but also take away the seeds leftover on the plants that I didn’t clean up when they all died in the fall and early winter things like native Ironwood Woodland sunflowers echinacea and ask her little birds like juntos and sparrows are constantly picking at the ground and flying under the feeder to pick up the scraps of what’s left over that dropped but then they migrate toward those plants it really makes me happy that all these efforts are not being wasted in the summer it’s a particularly enjoyable for me to watch the bees and the butterflies and even lesser-known pollinators such a wise and beetles land on the flowers and is it a wide variety of plants need it or not it’s still pretty cool to see one plant that really kind of shocked me as far as having a lot of different diversity of pollinators visit it was still little native bees wasps swallowtail butterflies that lay their eggs on it visited the dill and I just couldn’t bear 2 remove it from the garden when it was really time to do so so in the spring I think I’ll have a lot of different little tail plants popping out from where it all went to seed and dispersed All Over the Garden The spring am starting more native plants by sowing the seeds while it’s still cold so they undergo the cold stratification. They need to pop up in the spring so things like golden Alexander and pearly Everlasting which are two flowers that are native and attract different native butterflies Elsa want to find my peppers and tomatoes this year even though I know how to start them because I really find that greenhouse-grown tomatoes and peppers do a lot better in the garden the ones I try to start indoors myself I’ll probably start some herbs and some brassicas like kale and brussel sprouts so I really haven’t had much success with the brussel sprouts last year when I started spinach and various lettuce says they did pretty well when I transplant them into the garden so I plan on doing that again I’ll direct sow some peas carrots beets radishes and other root vegetables probably a couple weeks before the frost date comes in May so that they give a little bit of a head start and I think I’ll do the same with lettuce as well since there really is a short. Of time in the spring you can grow it before it gets too hot in the summer in the weather starts to bolt or try to flower and become bitterThe other thing I want to do is correct a misstep I made last year when I planted some of my flowering plants on the bottom level of my garden the red plants like red cardinal flower and salvia against which is pineapple sage attracts hummingbirds what was the use of planting them far away in the garden and not being able to actually see the hummingbirds when they come to visit

I started gardening when I move to Toronto which is a little bit Ironic considering that there’s a lot more land to Garden on in Texas but when I live there I live in Austin with roommates in apartments and really didn’t have my own space where I can grow things I declared myself to have a green thumb because I would kill any indoor plant that was given to me or that I purchased So eventually I just stopped buying them one of the things that it’s funny about growing plants indoors is that everybody over Waters them constantly and that’s what causes their death death by love and overwatering that first year in Toronto I grew tomatoes peppers basil planted some flowers like Marigold and has some peas growing up a trellis in the backyard we didn’t have much space and I had to lay down some cardboard and build a raised bed to make it happen but eventually the second year I used up a lot more space by making more red raised beds I really got into gardening do when we moved from Toronto to Niagara so I can go to school in the greenhouse technician program that’s when they really took off a lot of methods and the science behind growing and so that’s giving me the confidence to do what I do at my own home I’m really into native gardening as well as vegetable gardening and I really like growing weird vegetables but then sometimes it takes an effort to figure out what to do with them in the kitchen but my interest in gardening kind of stems from my interest in eating food and then learning how to cook food I like to eat at home as opposed to going out all the time now the focus has shifted a bit from gardening just for vegetables and herbs to planting a lot more native plants to attract pollinators and birds to the garden I really enjoyed this winter watching all of the birds come to the yard and eat from the feeders but also take away the seeds leftover on the plants that I didn’t clean up when they all died in the fall and early winter things like native Ironwood Woodland sunflowers echinacea and ask her little birds like juntos and sparrows are constantly picking at the ground and flying under the feeder to pick up the scraps of what’s left over that dropped but then they migrate toward those plants it really makes me happy that all these efforts are not being wasted in the summer it’s a particularly enjoyable for me to watch the bees and the butterflies and even lesser-known pollinators such a wise and beetles land on the flowers and is it a wide variety of plants need it or not it’s still pretty cool to see one plant that really kind of shocked me as far as having a lot of different diversity of pollinators visit it was still little native bees wasps swallowtail butterflies that lay their eggs on it visited the dill and I just couldn’t bear 2 remove it from the garden when it was really time to do so so in the spring I think I’ll have a lot of different little tail plants popping out from where it all went to seed and dispersed All Over the Garden The spring am starting more native plants by sowing the seeds while it’s still cold so they undergo the cold stratification. They need to pop up in the spring so things like golden Alexander and pearly Everlasting which are two flowers that are native and attract different native butterflies Elsa want to find my peppers and tomatoes this year even though I know how to start them because I really find that greenhouse-grown tomatoes and peppers do a lot better in the garden the ones I try to start indoors myself I’ll probably start some herbs and some brassicas like kale and brussel sprouts so I really haven’t had much success with the brussel sprouts last year when I started spinach and various lettuce says they did pretty well when I transplant them into the garden so I plan on doing that again I’ll direct sow some peas carrots beets radishes and other root vegetables probably a couple weeks before the frost date comes in May so that they give a little bit of a head start and I think I’ll do the same with lettuce as well since there really is a short. Of time in the spring you can grow it before it gets too hot in the summer in the weather starts to bolt or try to flower and become bitterThe other thing I want to do is correct a misstep I made last year when I planted some of my flowering plants on the bottom level of my garden the red plants like red cardinal flower and salvia against which is pineapple sage attracts hummingbirds what was the use of planting them far away in the garden and not being able to actually see the hummingbirds when they come to visit