I have always loved reading out loud. I like being read to and hearing stories told. But I especially love speaking the words myself. When I read I am often hearing the words spoken in my mind or reading aloud under my breath to myself. For me this also connects to loves of singing and poetry. I think words are amazing and I think voices are uniquely powerful.

Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water calls to be read loud. As discussed in previous posts, King is inspired by Harry Robinson’s oral syntax and often writes in a conversational or spoken manner, encouraging the reader to speak the text. Included in this effort to encourage his readers to speak, King’s novel is filled with allusions that can best be understood by being spoken. They’re basically puns!

Dr. Joe Hovaugh

Joe Hovaugh is an allusion to Jehovah. If, like me, you have very little religious knowledge, Jehovah is God’s true name in Jewish and Christian scripture. An English translation of the Hebrew word for God, Jehovah is revealed to be the name of God in The Bible. When we first meet Dr. Hovaugh, he sits behind his massive desk admiring his garden. This is the first of many connections to the Garden of Eden. Dr. Hovaugh represents a godlike figure in a number of ways throughout this novel. He is the head of the hospital where the four Indians are meant to be captive and he is tasked with tracking them down. He would, however, rather have their death certificates signed and be done with the matter. Quite a godlike action to decree that someone is dead without any proof. Marlene Goldman’s article Mapping and Dreaming, Native Resistance in Green Grass, Running Water also draws a likeness between Hovaugh’s massive wooden desk and the Tree of Knowledge. Cutting down the Tree of Knowledge to create what Hovaugh calls a “rare example of colonial woodcraft” (King, 11) creates a sense that colonialism has led to the destruction of knowledge.

Sally Jo Weyha

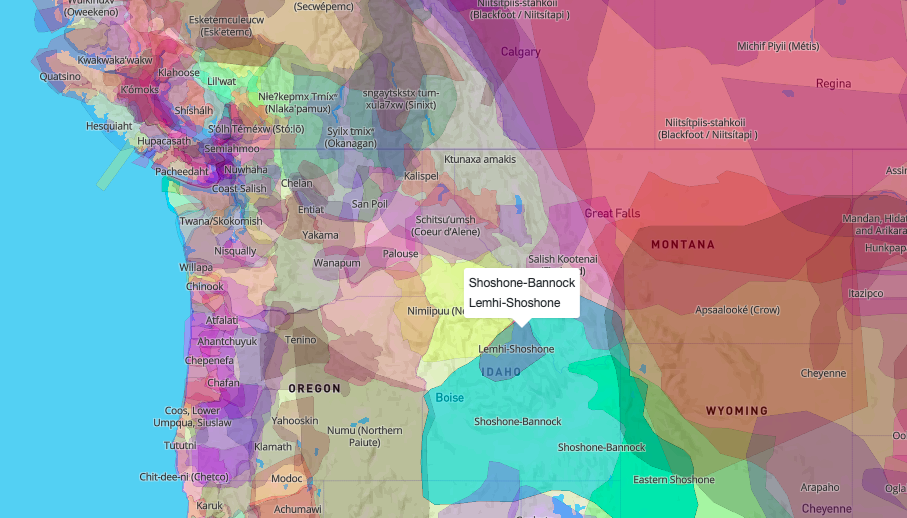

Sally Jo Weyha is an allusion to Sacagawea, a Lemhi Shoshone woman born around 1788 who was a guide and an interpreter for the Lewis and Clark expedition from Missouri to the Pacific Northwest (1804-1806).

[Image from Native-Land.ca where you can explore Indigenous territories, treaties and languages worldwide.]

Sacagawea was kidnapped by an enemy tribe early in her life and later became the property of (or was married to, depending on which text you read) French-Canadian fur trader Toussaint Charbonneau. Charbonneau was hired on to the Lewis and Clark expedition and Sacagawea accompanied (while six months pregnant and later with an infant). She is said to have been an integral part of the expedition and is held in high esteem in history books. History.com declares her one of the most memorialized women in the United States, and describes her impact as follows: “Her skills as a translator were invaluable, as was her intimate knowledge of some difficult terrain. Perhaps most significant was her calming presence on both the expeditioners and the Native Americans they encountered, who might have otherwise been hostile to the strangers.” In Green Grass, Running Water, Sally Jo Weyha is mentioned along with a number of other oral allusion names including Polly Hontas (Pocahontas) as Hollywood actors of various ethnicities (“Mexicans, Italians, Greeks, along with a few Indians, some Asians, and whites” (King, 93)) who are trying to make it in westerns and are stuck playing Indians every time. Sacagawea and Pocahontas both represent Indigenous people who are renowned in colonial history as helpers to white people. Their stories have been curated and morphed into fairy-tale-like narratives with a palatable Indigenous heroine, with mythical connections to the land and, as mentioned above, a ‘calming presence’. It is this stereotype of indigeneity that is working in Hollywood in King’s novel. If King feels that he is “not the Indian you had in mind”, Sally Jo Weyha likely is the Indian you had in mind.

Ahdamn

Although Ahdamn’s allusion to Adam from The Book of Genesis is quite obvious, King sends an interesting message through Ahdamn’s contrasting character traits. Unlike Adam, Ahdamn is not first in the garden. It is First Women’s garden and Ahdamn lives there without a clear origin. “That good woman makes a garden and she lives there with Ahdamn. I don’t know where he comes from. Things like that happen, you know” (King, 23). Right away, Ahdamn is not the central character and First Woman is surely not created from one of his ribs. Ahdamn loses more credibility in King’s story by his inability to complete the godlike task of claiming and naming things correctly. Pronouncing Ahdamn’s name when reading out loud I found two interesting things. The first was that when I first pronounced Ahdamn like Ah-dam (as opposed to Adam like A-dum), Ahdamn sounds like a dam. There is, perhaps, a connection here to later stories of the Grand Baleen Dam being the ruin of homes and communities. Another connection is the phrase ah, damn. Not only does this phrase connect Ahdamn/Adam to the damning and exile from the Garden of Eden, traditionally seen as Eve’s fault, but is perhaps a phrase to be uttered upon exile. Or, in Green Grass, Running Water, upon Ahdamn’s introduction into the story. Ah, damn.

Reading aloud

What I found stood out to me most when reading aloud was that I caught the flow and repetition within the novel more clearly. For instance, characters from one story line answering questions asked by characters in another storyline and the repetition of phrases throughout the novel. “Where did that water come from” mentioned in my previous post is an example of this overlapping.

I think King pushes his reader toward reading aloud in order to honour storytelling traditions and to encourage the reader to become the teller and the listener – another cyclical aspect of King’s writing. I also think that reading aloud forces us to grapple with what we do not know. When reading silently it is easy to skim or skip, even without meaning to. I read aloud to my students often and I am shocked sometimes to find names or words in texts I know well, that I’m actually not sure how to pronounce. When reading to ourselves we do not stop to investigate and we do not fumble. Reading aloud asks the reader/speaker to encounter that which they do not understand. The Cherokee words at the start of the novel are a great example of this. They are simple enough to skim past: Oh, another language. Let’s move on. But reading aloud we have to acknowledge that we do not know and are more likely to explore and research to find out. In addition when reading aloud we actually hold the words in our mouths and speak them into the world. “Higayv:ligé:i.” Hee..gay…vlee…giy…? No matter how fumbled or hesitant, the words exist when we speak them. They are words in the world, not just ideas of words.

————————————————————————————————–

Works Cited

Goldman, Marlene. Mapping and Dreaming: Native Resistance in Green Grass, Running Water. Canadian Literature, 161-162, Summer/Autumn, 1999, 18-41. https://canlit.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/canlit161-162-MappingGoldman.pdf. Accessed March 19, 2021.

King, Thomas. Green Grass, Running Water. Toronto, Harper Collins, 1993.

King, Thomas. “I’m not the Indian You had in Mind.” National Screen Institute, 2007, http://www.nsi-canada.ca/2012/03/im-not-the-indian-you-had-in-mind/. Accessed March 19, 2021.

Native Land. Native Land Digital, 2021. https://native-land.ca/. Accessed March 19, 2021.

Potter, Teresa and Brandman, Mariana. “Sacagawea”. National Women’s History Museum, 2021. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/sacagaweaAccessed March 19, 2021.

“Sacagawea”. HISTORY.COM, February 9, 2021, https://www.history.com/topics/native-american-history/sacagawea. Accessed March 19, 2021.

“Who is Jehovah?” Jehovah’s Witnesses. https://www.jw.org/en/bible-teachings/questions/who-is-jehovah/. Accessed March 19, 2021.

Hi Laura,

Your excellent discussion of Sally Jo Weyha / Sacagawea on p. 182 and that entire section about Charlie and Portland’s road trip to Hollywood reminded me of something that recently shocked me from the French film critic Jean-Louis Rieupeyrout (125). He quoted the St. Louis Globe, “… the white man is a wave that conquers, colonizes, and brings progress. Let us not shed tears over the miseries and the sad fate of the poor Indian….” Rieupeyrout was writing at the height of the Western genre, but the world has come a long way, it seems to me (though the Globe is still there), and no news-source would admit to writing such hate-speech now, I hope. But Rieupeyrout, in 1951, seems to approve of the genre, saying that viewers ignore the mostly bad reviews because they love the films. I’m hoping Western society is on the move, slowly coming to our senses, and most movie-goers would be offended to see 1951-era pictures now, except in historical context. But I’m still shocked that the St. Louis Globe could’ve ever held such awful ethics.

Cited:

Rieupeyrout, Jean-Louis. “The Western: A Historical Genre.” The Quarterly of Film, Radio, and Television, vol. 7, no. 2, 1952, pp. 116-128

Hi Joe. Yeah – this is an intense comment. In some ways I think you are right that the world has come a long way and in other ways I wonder if methods have just changed? You’re right that it seems no longer tolerated to write something like this in a professional newspaper. But, of course, just because the media isn’t writing it explicitly doesn’t mean it is not being written or spoken or thought…

Case in point:

https://globalnews.ca/news/2901979/saskatchewan-councillor-resigns-after-comment-about-killing-of-aboriginal-man/

Recent news is discussing the findings of an investigating into the handling of the case that shows a number of horrible ways the event was mishandled. The one that connects with our discussion about Indigenous stereotypes is that when RCMP went to Boushie’s home, after he had been killed, they showed up with weapons drawn. And when his mother fell to her knees upon hearing the news they asked if she was drunk and apparently multiple officers checked her breath. These stereotypes and prejudices run so deep.

https://www.aptnnews.ca/national-news/colten-boushie-rcmp-family-report/

A heavy response – but there you have it.

Thanks for your comment.

Hi Laura,

I absolutely loved your analysis of these different ‘disguised’ names throughout the novel. I especially love your point about Sally Jo Weyha/Sacagawea being “the Indian we had in mind” – I thought it is a super clever way of bringing King’s video/lecture into the conversation, especially given the theme of Indigenous pigeonholing in media. I also thought you made some excellent observations about Joe Hovaugh/Jehovah and his garden. There are also moments where Dr. Hovaugh’s language parallels Genesis, such as when he looks out on his garden and is “pleased” (King 16). I would add that his full name – Joseph – is also a personage in the Bible, Jacob’s son who is sold into slavery because of his brothers’s jealousy. I’m not sure what bearing this is meant to have on our understanding of Joe Hovaugh, but knowing Thomas King, I can hardly believe this was unintentional. In any case, I find it quite interesting that King chose to make his God character a doctor in specifically a psychiatric hospital; why do you think that this is the position that King gives his ‘God’ character? It does not really seem like THAT powerful of a position for a God character to have.

King, Thomas. Green Grass, Running Water. Toronto: HarperPerennial Canada, 2007. Print.

Great question Victoria!

I think maybe the fact that this isn’t really a very powerful position is sort of the point. Similar to how King writes that GOD is a mixed up version of Dog (Coyote’s dream), maybe he is purposefully creating a God-like figure that is not very powerful. He is sort of alone in his empty hospital and behind his big desk with his garden, and he doesn’t seem to actually want to do much. Also, I guess the head of a hospital is stereotypically quite a powerful role within western colonial culture. Not sure about the specific role as head of a psychiatric hospital…

Thanks for your comment!

Hi Laura,

I really enjoyed reading your blog post, particularly on the sections where you describe the importance of reading aloud and the benefits that come from it. From my experiences of reading stories, I think part of that investigative aspect of reading out loud allows us to remember the story in a deeper context as well. For example, there was a psychological study done at the University of Waterloo which tested how much we remember when we read aloud versus reading silently. The results suggested that we are able to remember close to 30% of what we read when we read aloud whereas we tend to only remember 10% when we read silently. My point is that we tend to have a better memory of the stories we study when we read it aloud which allows us to share more knowledge around the context of these stories.

Why you should read this out loud. (n.d.). Retrieved March 22, 2021, from https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200917-the-surprising-power-of-reading-aloud

– KO

Hi Kyle,

Good point! This makes total sense to me. I have done a lot of memorizing for theatre and I always speak everything out loud for it to stick. It’s interesting to take this idea of speaking being connected to memory and apply it to our understanding of oral storytelling. We’ve talked in this class a bunch about the process of storytelling being an act of creating and remembering over and over again.

Thanks!

Hi Laura,

Your blog post was very enlightening to read. I find myself somewhat embarrassed to have missed the allusion to the true people in the names such as Sally Jo Weyha and Polly Hontas.

I was particularly interested on your topic of Ahdam. I hadn’t thought of it as being “a dam” before you mentioned it; I was stuck on calling him “Ah, damn.” Though my inclination to say damn rather than dam I think has to do with where Ahdam is introduced into the story. He almost seems a bit of a nuisance with his getting the naming of creatures incorrect, and mostly being in the way. I wonder if perhaps we could look at this allusion further and think about whether or not this character stands in for Christianity in a general sense? Ahdam does seem to be there just to stir up unneeded trouble; though maybe his character is more about falling into “the category” of Indian that the white man wants him to be (thinking of how he gaily started to drawn pictures are the Fort once captured and just having a great time of it in general).

Either way, I liked you analysis of the character. Thank you.

~Cayla

Hi Cayla,

This book is so full that we all missed some things, I am sure. I like how you’ve proposed that Ahdam could stand in for Christianity in general. This, along with other things in the novel, paints a pretty clear picture of King’s views on Christianity!

Thanks!