This week’s material was a little more familiar to me and the task was fun to complete. It reminded me of the game Advert Attack I played when I was in elementary school, a game where you had to close different ads and pop-ups in order to steer your rocket ship to the finish line. This game was on Neopets, a virtual pet website that had been criticized for exposing children to subtle advertisements (later on, the company revised their website interface to ensure ads were clearly labelled as such). User Inyerface was more frustrating than challenging. As a person who has grown up using the internet and am still on it a lot, it was easy for me to see through the little tricks (though I’m sure that knowing I was going to be tricked contributed to my success).

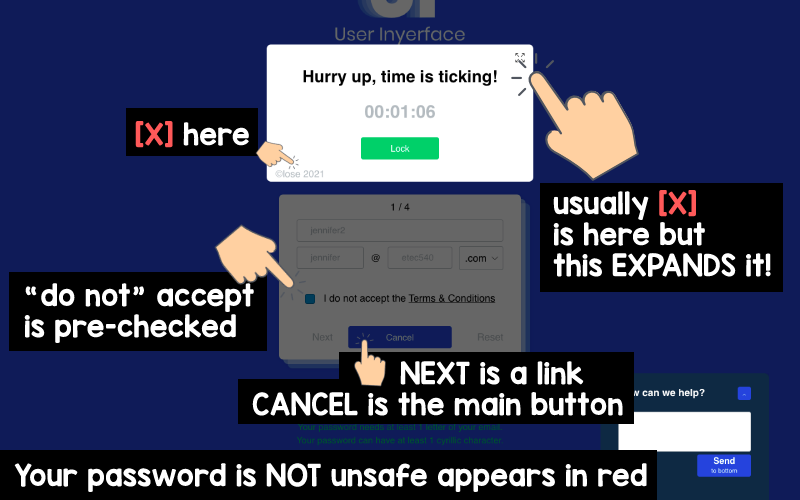

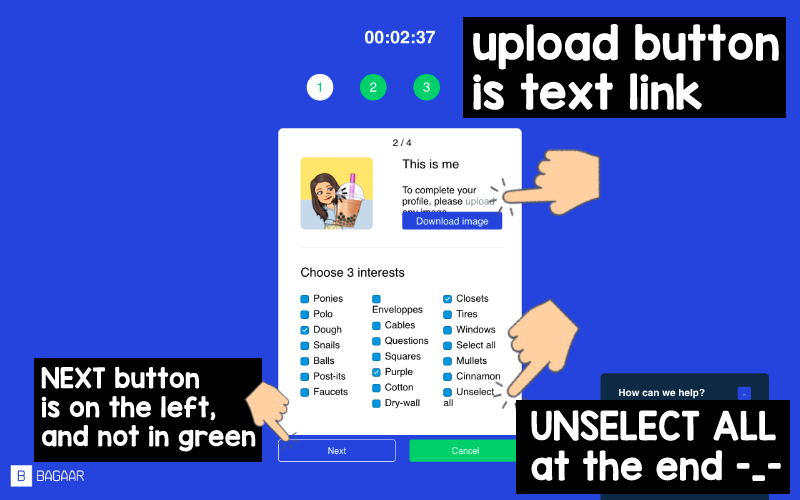

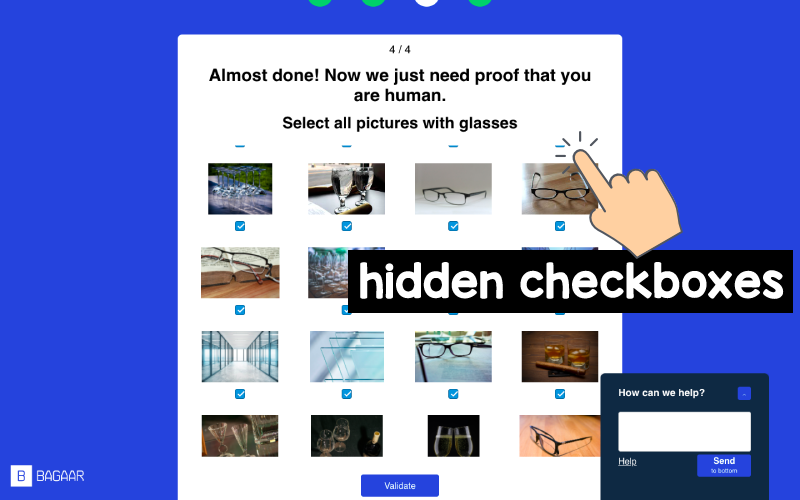

Here were some things I noticed while completing the game:

I’d imagine my parents would need a lot more time to go through this. First of all, English is their second language so reading through all the text would be time-consuming. If they were hasty, they may click on what looks obvious like a button (when in fact, you had to click a text link) which may lead them to agree to certain things or download programs they didn’t mean to. Speaking from experience of having to help them un-download unwanted apps, these “dark patterns” are definitely effective, especially against those who do not or cannot understand everything. The dark patterns work hand-in-hand with attention economy: there are limited blocks of attention and websites take advantage of our desire to move quickly, so that we can consume the next thing. Hence, tactics like ensuring the default options benefit the business at users’ expense but without them knowing, are often employed, as short-term quantitative measurement is much faster and easier to attain than building up credibility and brand image (Brignull).

Tristan Harris (2017) in his TED Talk, “How a handful of tech companies control billions of minds every day,” describes attention economy as this race “to the bottom of the brain stem” of our lizard brain (3:01). In particular, his example of the senseless ‘snap streaks’ illustrates how as consumers, we can be easily tricked into keeping up with something that doesn’t really matter. But teenagers aren’t exclusively victims of this tactic: mobile app games encourage us to log on every day for a free ‘prize’ and if we logon ten days in a row, we get a ‘super prize’ to use in the game.

In our discussion of algorithms last week, UI works with artificial intelligences on these websites to learn my viewing patterns and curate a feed that will keep me scrolling. The UI of Instagram makes it really easy to keep viewing ‘the next post’ (e.g., once I click on a certain post, it automatically scrolls down to the next post that is of a similar topic as the first one). A while ago, Instagram changed their UI completely and replaced the “likes and notification” button with a shopping tab! Users who were used to clicking that area were now forcefully brought to the shopping page.

It’s certainly unsettling to recognize that I am a target of engineers who “knew exactly how [my] psychology worked and orchestrated [me] into a double bind” with my social media (4:20). Yet at the same time, I couldn’t get on board with Harris’ idea of replacing timelines with what we want to ‘actually’ do in our lives. While I understand that the amount of screen time should decrease for most of us, there seems to be this bias of favouring face to face contact as more genuine and real. Speaking for myself, I do enjoy my screen time and endlessly reading articles. I’m fully aware that my internet has been ‘tailored’ to me to keep my attention. I know full well that not everyone’s feeds are filled with squishmallows, BTS, and news about anti-Asian hate crimes. Are companies benefiting from my attention and my data when my purchasing habits have not changed much, and my relationships with others have not been negatively effected?

However, Harris’ ending message does resonate with me and that is the need to figure out “what our boundaries would be” and to have those “honoured and respected” through the help of technology (14:02). Throughout this whole post, I’ve only reflected on myself but I do wonder and worry for my students who are already saturated in this world since they were little, and whether that would make them more savvy or more complacent. I agree with Harris that the first thing we must do is to be aware of how persuadable we are, and that this is especially important to teach students. My students are fairly defensive about their social media use and they already know the stigma and negative effects that come from it. I think teaching dark patterns and showing them why and how these companies trick all of us, is a good way to present this information to them so that they can make better, more informed choices.

References

Bagaar. (n.d.). User Inyerface. https://userinyerface.com/

Brignull, H. (2011, November 1). Dark Patterns: Deception vs. Honesty in UI Design. A List Apart. https://humanparts.medium.com/laziness-does-not-exist-3af27e312d01

Harris, T. (2017, April). How a handful of tech companies control billions of minds every day [Video]. TED. https://www.ted.com/talks/tristan_harris_how_a_handful_of_tech_companies_control_billions_of_minds_every_day

Hi Jenn!

I love the screenshots you took to really emphasize your frustration with this activity. I share your frustrations! I also can relate to your comment about growing up with the internet and about being able to see through some of the tricks in the game. This comment reminded me of the terms “digital natives” and “digital immigrants” and how older generations would not only be dealing with navigating dark patterns, but how just using the technology could be a challenge for them!

Hi Sarah, thanks for your comment! As I was researching for my final project, I came across those terms too. A different way of looking at that could be digital humans, and our ability to arrive at that stage where we are capable of navigating technology and handling dark patterns, regardless of age (as there are some young people who are just as bad at it while there are older people who have caught on very quickly). However, I completely agree with you that generally, from experience, the older generations do find it very challenging to not be tricked!