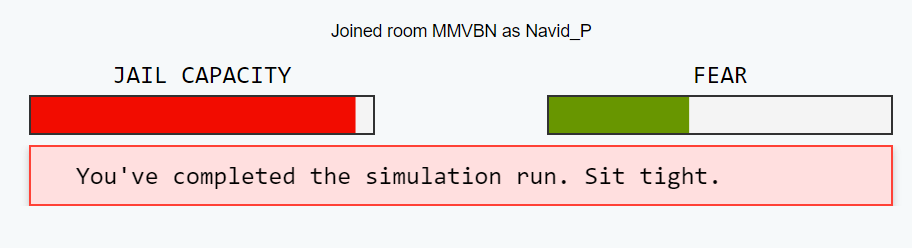

Task 11: Detain/Release

The detain and release task had me change my own internal bias midway through the activity as I noticed a trend and adjusted my own internal set of rules, my algorithm, for judging if a criminal should be detained or released. Due to my own internal belief in fairness I favoured “[sacrificing] enormous efficiencies for the promise of fairness” (O’Neil, 2017a). Which meant individuals who had minimal evidence in their court cases and who were not at risk to reoffend were released. Usually those with drug offenses were marked as low risk of flight and reoffending but I noticed a trend developing, most of the drug offenses I released with low risk of flight ended up not appearing for their court date which resulted in me changing my detainment protocol and becoming far more willing to detain individuals. At the same time, crimes that seemed less dangerous such as Fraud ended up committing another violent crime.

The algorithms seemed to relate fraud with low chances of reoffending which show an “algorithm going bad due to neglect” (O’Neil, 2017b). Which made me realise that even though Jack Maple had good intentions to make a safer city for New York and how COMSAT initially was effective, it was the misunderstanding of its efficacy and bureaucratic malpractice that led to its abuse by authorities (Vogt, 2018). Even algorithms for social media were initially intended for users to find like minded groups and products for their interests. Yet now they are being used by the highest bidder to push forth a specific narrative or product to enrich the few or push an ideological ideal.

AI-informed decisions just like algorithms were designed to make the lives of workers and legal venues more objective and efficient. But these AI programs themselves are built with bias due to the prior cases and case laws already present in our world, inherently creating an ill-informed decision. Algorithms and AI should not take the final decision, but instead should be used to advise and recommend a path which should ultimately be left up to the judge, a council, or for a classroom, the teacher.

References:

O’Neil, C. (2017a, April 6). Justice in the age of big data TED. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

O’Neil, C. (2017b, July 16). How can we stop algorithms telling lies? The Observer.

Vogt, P. (2018, October 12b). The Crime Machine, Part II (no. 128) [Audio podcast episode]. In Reply All. Gimlet Media.

Great post, Navid! Your mention of the “algorithm going bad due to neglect” (O’Neil, 2017) made me think about how quickly that can happen when we blindly trust systems without constantly questioning the data behind them. I teach in a school with a very diverse student population, and I’ve been thinking a lot about how similar patterns might play out in education; like predictive tools used for early intervention or behavioral tracking. If these tools are based on biased or incomplete data, they risk reinforcing the very inequities they claim to fix. I am wondering, how do you think educators can actively challenge or counteract algorithmic biases in predictive tools, especially when these systems are often implemented at a district or policy level?