Title:

⚔️⭐????

Synopsis:

????♂️????????

????????????♂️

????????????

????♂️➕????????☮️

????????????♀️

????♀️????????⁉️

????♀️????????????♂️

????♀️????????????

????♂️????????????

????♀️➕????????????????

I’m currently watching numerous series, but when I consider how many of these series would be widely known, I settled on this particular one. For the title I relied on words/parts of words to translate to one symbol, while for the synopsis I went with a combination of words and ideas.

To connect this task with Kress (2005), perhaps due to the translational nature of this assignment I found that I followed the temporal conventions of written English text. Events are ordered in rows going left to right, and later events are placed below earlier ones. In this task, the emoticons are more “text” than an image where one could use the affordances of space to provide different messages.

As I went through this task, I found myself contrasting alphabets as discussed in Gnanadesikan (2011) with logograms as discussed in Bolter (2001). I find that unlike alphabet based languages, logographs such as emojis (and as I’ll discuss later, Chinese) do not have the base unit, an alphabet. While English words have base units in Roman alphabets that can be arranged to produce numerous combinations, and the arrangement of the alphabets provide hints to the sound of the word, emojis cannot be broken down further. The availability of a limited amount of base units (too many base units and a keyboard may be unwieldy) contributes to the speed at which one sends information: with English, by memorizing the locations of all the base units on a keyboard, I can type quickly to combine base units into words and transmit that to others. With emojis that lacks base units and are numerous, I have to constantly go through all the emojis listed to select the correct one, as seen below in my screenshot of the emoji library of Signal, one of the instant messaging apps I use. Similar to the point made in Gnanadesikan 2011, “to make a truly different symbol for each word of a language would result in far too many symbols” (p. 6).

![]()

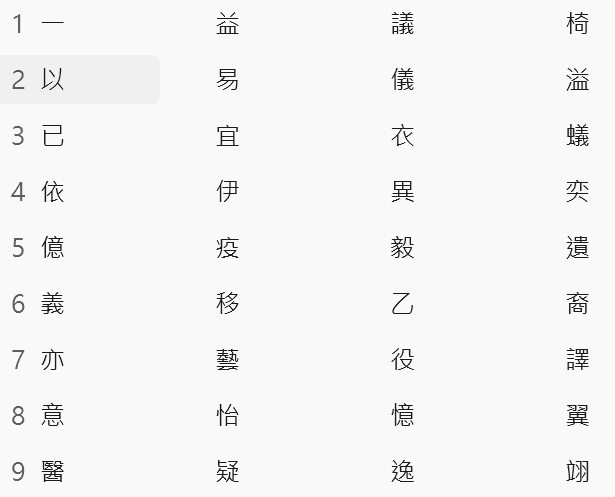

I found a similarity between this process and the pinyin Chinese input method, where one types the sound in English, look at the words/symbols/characters that come up, and select the correct one. For example, typing “yi” provides the following this of homonyms using the Microsoft Windows Traditional Chinese input method:

Like emojis, a list is given, each with a different meaning, and I need to select the correct one. Similar to the points brought up in Gnanadesikan (2001), I believe the root cause of this similarity is due to the lack of an alphabet and a wide variety of symbols available, resulting in an extra step needed to select from a list instead of simple typing (although in Chinese input method, this process is slightly sped up, as the nine most commonly used symbols can be selected with a press of the corresponding number key).

One other connection I made between emojis and Chinese, thanks to Bolter (2001), is that they can be both considered as logograms. In Chinese, the characters for one, two, and three, are essentially number of sticks somewhat similar to Roman numerals (一,二,三). Field is 田, showing sectioned off rice patties, while the character for mountain, 山, showcases peaks. Door/gate, 門, looks like old saloon doors, and river looks like 川.

If this is the case, then there is an implication that there would be less usage of emojis for people typing in Chinese since there is no need for an image to replace a character/symbol/word, since the character/symbol/word itself takes up as much as an image and would take around the same amount of time to input.

Indeed, I find that my conversations with family members and friends, “stickers,” rather than emojis, are used instead. Stickers are popular stock images that one can send in, for example, Line, the top instant messaging app in Taiwan. Unlike emojis that depict one object, stickers typically depict a situation. For example, as shown in the screenshot below, one of the default stickers in Line is a bear is holding a mug of beer, emitting a music note, while a plate of a burger and some fries are in front of them. To translate this sticker, it would take approximately four emojis. As per arguments made in Kress (2005), stickers are images that can utilize space where all elements are simultaneously present, as opposed to emojis in this exercise that are more “text” that have a logic to their order.

This task also led to a lot of comparison between English and logographs such as emojis and Chinese. As aforementioned, English is made up of base units, and emojis are not. Although Chinese has visual base units called radicals (for example, 忍, to endure, is a combination of 刃, blade, and 心, heart), they’re not widely used as an input method, and I suspect the main reason is visual (text) vs aural (speech). The radical Chinese input method is not popular since radicals are based strictly on written text, while the popular Chinese input methods, pinyin in China and bopomofo in Taiwan, are based on sound. Pinyin uses the Roman alphabet for Chinese word sounds, while Taiwan’s bopopmofo creates a new series of symbols for the sound of a character.

References

Bolter, J. D. (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Gnanadesikan, A.E. (2011). The first IT revolution. In The writing revolution: Cuneiform to the Internet (pp. 1-12). John Wiley & Sons.

Kress, G. (2005), Gains and losses: New forms of texts, knowledge, and learning. Computers and Composition, 2(1), 5-22.