Throughout history, fishery has been an important pillar industry in Norway. Norway has been one of the world’s leading fishery country due to its geographical characteristics, a more than 83000 km coastline and moderate climate. In 2006, with catches of around 2.4 million tonnes, Norway was the 10th largest fisheries producer in the world. In 2009, Norway ranked eleventh in global capture fisheries production. Norway’s fishing and fish farming together account for 0.7 percent of the GDP in 2010 (FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture 2011)[i]. Cob and herring are the most important stocks in fishery industry in Norway along with sea and river fishing of salmon, and capelin.

Government intervention in fishery industry started early in Norway. In this blog, I will focus on one of the fishery policies in Norway known as the Individual Vessel Quota system (IVQ-system).

(1) What is IVQ-system and its implemented time, and specific limits?

In the last 1980s, there was a sudden and unexpected sharp decline of the Norwegian Arctic cod stock resulting in a most severe crisis in Norwegian fisheries in modern times. In response to the situation, first, the total quota was reduced significantly, from 630 000 tons in previous year to 340 000 tones. Besides, in 1989, the coastal fisheries were closed for almost the whole year (closed after only three and a half months). Then, in the fall of 1989, the Individual Vessel Quotas system (IVQ-system) was established and implemented for the 1990 season in the costal fleet (Fisheries Policy Reform: National Experiences 2011)[ii].

“IVQ-system is a management mechanism to distribute the Norwegian total allowable catch (TAC) amongst different segments of the fishing fleet. The fleet is divided into several groups according to size and fishing technique (trawlers, purse seine, etc). Each vessel group is then allocated a group quota which is then shared among the participating vessels in fixed and (more or less) guaranteed portions.”

–Fisheries Policy Reform: National Experiences 2011.

Therefore, IVQ-system’s geographic and biological reach would be consistent with that of Norwegian TAC.

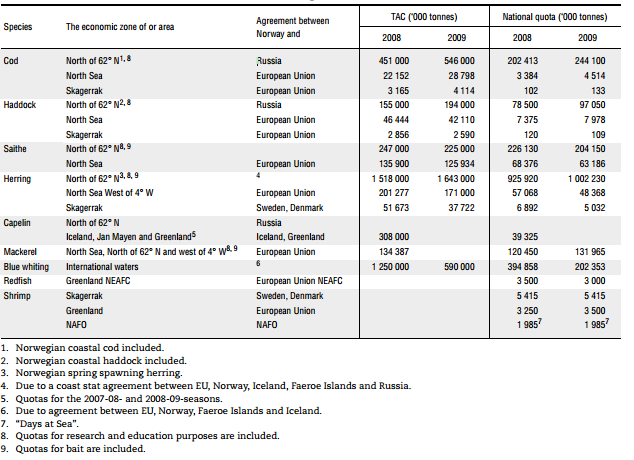

Due to the special geographical location of Norway, most of its commercial fishery stocks are shared with other countries. IVQ-system is the quota for each vessel group (TAC divided by vessel groups), so it is implemented when the TAC is settled through international negotiations (mainly between Russia and other European countries). Important species included in TAC and IVQ-system are cod, haddock, salthe, herring, capelin, and so on (OECD Review of Fisheries 2011)[iii]. The specific limitation of different species are shown in the table below.

Table 1TACs and national quotas in 2008-09 for some important species

Resource: OECD (2012), “Norway: Norway”, in OECD Review of Fisheries 2011: Policies and Summary Statistics.

According to the regulation, trade in quota is not allowed in IVQ-system, although there is an informal market.

(2) Enforcement mechanism

The IVQ-system was a two-tiered system. The vessels or fishermen were divided into two groups, the most active vessels and the less active vessels, according to the quantity of cod landed in the years from 1987 to 1989. For the most active vessels (the priority group I vessels), the quotas were exclusive, it means the vessel owner had the decision-making power to decide when or where to fish under the quota requirements. For the less active vessels (group II vessels), they were allowed to fish under a group quota, this implies the fishery activities would be more competitive. There were no restrictions for fishermen to participate to this fishery group, as long as they fulfilled the obligation and requirements of being a registered fisher. The difference of quota levels between two groups was relatively large, the quota allocated to group II was only about 10% of that allocated to group I.

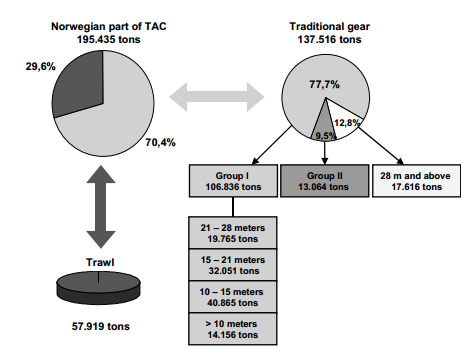

Figure 1Northeast Atlantic Cod. Distribution of National Quota 2002

Resource: Country Note on National Fishery Management System – Norway

As shown in the figure above, the Norwegian part of the TAC is divided into quotas for each vessel group. Then each group quota is shared between vessels within the group according to the size of the vessels (OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Norway, 2011)[iv]. There are three stages of the quota system: the negotiated national quota – the group quotas – IVQ-system.

(3) Potential advantages and disadvantages

The initiatives of the IVQ-system was to deal with the resource (cod stocks) crisis and supposed to be abolished once the situation returned to normal. However the IVQ system has become permanent. After the crisis, the main goal of the IVQ-system has been linked to two main pillars: one is the secure a decentralized ownership and the other one is to avoid unprofitable overcapacity as means to provide an economic viable fleet (Standal and Aarset, 2008)[v]. A major advantage of IVQ-system compared to the ordinary individual transferable quota system is that IVQ-system integrates quotas and vessels and is a bundled system. The IVQ-system has led to a huge concentration of quota ownership and severe changes in fleet structure.

However, there are some arguments about the disadvantages of this quota system. Some argues that political decision system cannot provides the most efficient allocation of a society’s resources, which is a common argument on the government intervention. Others argue that the system did not consider the vessels’ poor economy and the potential for changes in ownership, and Norwegian management regime seems to be the very suited for the strongest actors rather than some small companies in rural fishing-dependent areas (OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Norway, 2011). These concerns may lead to the opposite side of the original goal of IVQ-system.

Together with other quota policies, the Norwegian fishing industry has changed from a heavily subsidized and capital highly concentrated industry to a relatively competitive one. Based on the results of-IVQ system, the government intervention has leave the duty of adjusting the capacity to those competitive power in the industry, which means it could secure high profit for who has the available resources to improve fishing technology. However, to be an efficient management instruments, IVQ-system requires improvement and adjustment, such as introduction of tradable quota which could encourage the fishermen’s per

[i] FAO Fisheries & Aquaculture – Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles – The Kingdom of Norway (2011). http://www.fao.org/fishery/facp/NOR/en#pageSection2

[ii] OECD (2011), “Introducing market-based reforms to manage overcapacity in Norway”, in Fisheries Policy Reform: National Experiences, OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264096813-5-en

[iii] OECD (2012), “Norway: Norway”, in OECD Review of Fisheries 2011: Policies and Summary Statistics, OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/rev_fish-2011-33-en

[iv] OECD (2011), “Nature and Biodiversity”, in OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Norway 2011, OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264098473-10-en

[v] Dag Standal, Bernt Aarset. (2008). The IVQ regime in Norway: A stable alternative to an ITQ regime? Marine Policy, 663-668.