Hi again! Wow, term has flown by in the blink of an eye. Its hard to believe that another school year is over, but when I look back on everything I’ve learned over the past few months, I can see how much my perspective and world view have changed as a result of fully immersing myself in my courses and the GRS community. One of my favourite parts of university in general is being able to make connections between different seemingly unrelated disciplines. This post is inspired by the overlap between my gender studies course Decolonizing and Feminist Perspectives from Local to Global (GRSJ 102) and my Indian history course History of India (HIST 273). I enjoyed the two individual courses immensely, but taking both simultaneously helped me to connect with the material on a deeper level and identify linkages between theory, concept, and reality.

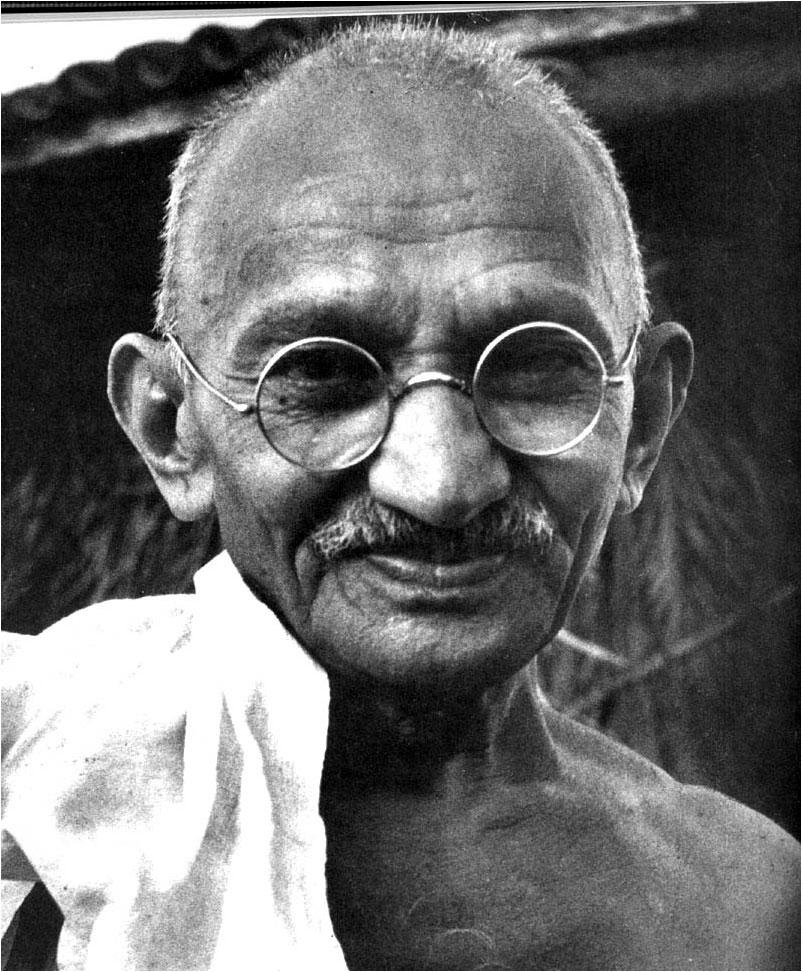

The following essay is a reflection on the role gender ideology played in Mahatma Gandhi’s Nationalist movement in pre-Independence India. It touches on themes of civilization vs. savagery, colonialism, religion, and politics in order to explore the socio-political milleu in which Gandhi espoused his ethics of non-violent or “passive” resistance.

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, affectionately referred to as Mahatma, or Saint by his supporters, was a prominent figure in the Indian nationalist movement of the late 19th and early 20th century. A revolutionary philosopher and activist, Gandhi pioneered the use of civil disobedience as a tool for political reform; moreover, his platform of non-violence and “passive resistance” set a precedent for independence movements around the globe, and permanently altered the dynamic between colonizer and colonized in the late modern world. Through his literary legacy, it can be seen that concept of civilization was central to Gandhi’s construction of British colonialism as an oppressive force in the subcontinent. Although Gandhi uses the term “civilization” to describe the socio-political milieu in both Britain and India, it is clear that he perceives British and Indian civilization as distinctly different entities. Gandhi characterizes British civilization as competitive, capitalist, and materialist; moreover, he attributes masculine traits such as dominance and violence to British colonial rule.[2] Conversely, he characterizes Indian civilization as spiritual and moral, and evokes the image of a “Mother India,” to which he attributes feminine traits such as nurturance and love. Through gendering the concept of civilization, Gandhi suggests that Britain and India are fundamentally different, and that British values are ultimately incompatible with India’s true nature. Thus, Gandhi portrays colonial rule in India as an aberration, and suggests that masculinization is the true “disease” of British civilization.[3]

Gandhi’s idea of civilization also challenges conventional notions of masculine strength and female frailty. In defiance of the Orientalist perception of a weak, effeminate India, Gandhi envisions “Mother India” as inherently powerful and strong. This vision plays an instrumental role in Gandhi’s political ideology, as both satyagraha and passive resistance emphasize feminine traits such as compassion, truth, and love.[4] In addition, the philosophy of passive resistance epitomizes self-sacrifice and suffering – traditionally aspects of a woman’s dharma – as courageous and moral means of challenging colonial oppression.[5] In contrast, Gandhi portrays violence as a cowardly act, suggesting that masculine traits such brute force and aggression are inferior to the feminine strength espoused by his political doctrine. As such, Gandhi encourages his supporters to “be strong as a woman is strong,” thus legitimizing female strength and non-violent means of revolt.[6]

However, Gandhi is inconsistent in his discourse on gender, violence, and passivity. In describing India as a “young woman attacked by a soldier,” he advocates that she “fight back with teeth and nails rather than submit to rape”; this metaphor is at odds with Gandhi’s platform of non-violent resistance, as it implies that “violence [is] preferable to cowardice.”[7] Furthermore, it contradicts Gandhi’s previous assertion that violence is itself cowardly, and that self-sacrifice is the only virtuous means of challenging oppression. In addition, Gandhi expresses conflicting views on femininity and masculinity. Despite encouraging members of the nationalist movement to embrace certain feminine traits, Gandhi suggests that the integrity of masculinity is important to preserve. He insists that “true men” stand up to their oppressors, fear “only god,” and practice brahmacharya (chastity); moreover, men who fail to conform to these standards are at risk of “emasculation.”[8] This fear of losing one’s “manhood” implies that femininity is inferior masculinity; although this notion reflects the patriarchal milieu of the time, it subtly undermines Gandhi’s promotion of female strength as the key to India’s liberation.

In this way, it is clear that Gandhi does not seek to eradicate the gender binary or establish gender equality within Indian society. Instead, he attempts to redefine masculinity within the existing socio-normative framework, in order to encompass aspects of satyagraha and passive-resistance that are conventionally labeled as feminine or weak. Just as Gandhi does not consider civilization itself to be evil – rather, the manifestation of civilization in British society is vilified – he does not perceive masculinity to be inherently wrong. However, he denounces traits commonly associated with the western construct of masculinity – such as aggression, violence, and dominance – which he perceives as “[un]natural to Indian soil.”[9] Therefore, the true “disease” of British Civilization lies in is its embodiment of western masculine traits, which threaten to corrupt Gandhi’s core values of peace, love, and truth. As such, when Gandhi advocates for India to harness a “’woman’s strength,” he does not imply that femininity is superior to masculinity; rather, he suggests that the success of India’s independence struggle hinges upon its ability to embrace a masculinity characterized by “soul-force,” self-sacrifice, and swaraj.

[1] Muhammad Iqbal, quoted in Barbara D. Metcalf and Thomas R. Metcalf, A Concise History of Modern India, 3rd ed. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 166.

[2] Barbara D. Metcalf and Thomas R. Metcalf, A Concise History of Modern India, 3rd ed. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 172.

[3] Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, Hind Swaraj (Gujarat: Gujarat columns of Indian Opinion, 1909), 7.

[4] Gandhi, Hind Swaraj, 8-9.

[5] Ibid., 9.

[6] Metcalf & Metcalf, Modern India, 172.

[7] Ibid., 206.

[8] Gandhi, Hind Swaraj, 11.

[9] Ibid., 14.

Image: Unknown. (20 Aug 2010). Gandhiji. [photograph]. Retrieved from http://antaryamin.wordpress.com/2010/08/20/how-mahatma-gandhi-influenced-the-influencial-minds/