Introduction

Since Korea’s economic crisis of 1997, Korea’s job market has been undergoing dramatic modification. Higher education has been rapidly growing and economic growth has provided a job market for college graduates. Rapid industrialization and competitive work environment, however, have brought about many cultural issues in recent years, affecting the Korean employee’s work values, attitude, and behaviour. In this paper, the recent drama Misaeng (tvN, dir. Kim Won-Seok, 2014) will be used to support my argument of how Korean workplace become an intense and pressured environment due to hierarchical behaviour and gender issues.

Misaeng is a South Korean television series directed by Kim Won-Suk. This 20-episode Korean drama aired in 2014, centered around four interns and mainly showing a story of corporate office workers in the trading company One International. The drama follows main protagonist Jang Geu-rae, a young man who failed to become a professional baduk player. Through a family acquaintance, he is hired as an intern at a large trading company One International with only a high school equivalency exam on his resume. He begins work life as the intern of Sales Team 3 and meets his boss, Chief Oh Sang-Shik, who is a workaholic and has a warm personality. Throughout the drama, we see a wide spectrum of characters who, with their varying personalities, navigate the interpersonal work relationships and office politics in the work force but also their own personal lives. When the drama aired, Misaeng received lots of responses. Many people saw their own lives reflected in the drama because of its realistic portrayals of work life and its associated struggles and politics.

According to Choi (2007, 213), multi-level analyses of data from a Korean electronics company showed that gender and hierarchical status and group diversity in hierarchical status were negatively related to employee creative behaviour. Workers not only receive pressure from job-related stressors but also interpersonal stressors. In this paper, I am going to argue that Korean work environment is so intense and pressured due to interpersonal problems involving generalized hierarchical behaviour and gender issues are highly prevalent and significantly linked with Korean workplace.

Hierarchical Behaviours

South Korea is a country with high power distance and hierarchy (Lee 2012, 184). People or groups are ranked one above the other according to status, authority and job titles. Koreans are used to rely on hierarchy because it can help a system to manage well and classifies things according to relative importance. In South Korean society, authority is traditionally concentrated at the higher levels in the hierarchy and authoritarian styles are generally accepted (Chen 2004). Limitations are set by the hierarchy of the company and how much power you have. However, through the realistic reflection of Korean office life in the drama, a deep and dark side of hierarchy in the workplace has been revealed, and many hierarchical behaviours between different positions are shown in Misaeng.

Mr. Choi (Executive director): “Shouldn’t the Resource Team be doing this (the North Korean Earth Resources Project) instead?”

Everyone remains silent.

Mr. Choi: “Of course this should be done by the Resource Team. Mr. Kim, since it’s overlapping, why don’t we just make it one item?”

Mr. Kim (Department Head): (after a long time of silence) “Yes, sir.”

Mr. Choi: “Why go through all this when we have professionals? Find an item that fits Sales Team Three.”

Misaeng ep. 7 (1:03:10-1:04:21)

Figure 1. The executive director orders Resource Team to take Sales Team 3’s project.

In Misaeng episode 7

After Mr. Oh and Sales Team 3 go through all the difficulties and find the solution for the project, Mr. Choi realizes it is a good project and it will get an outstanding achievement. He took Mr. Oh’s idea and grabbed this project. In Figure 1, we can see that the executive director tells Sales Manager Kim that the resource team will be taking (stealing) this project. It is not a rare scene in the drama that the high-ups try to take subordinates’ good work as their own. Just because the executive director has a higher title and an older age compared to most of the people in the company, he can order his subordinates do anything he wants and subordinates dare not refuse the request. This rigid hierarchy in Korea leads to unfairness and a lot of bullying psychologically and physically at all levels. Pressure and obstructs brought by the superiors make for a much more challenging and ineffective working environment. Hard works are easily being taken away and people have to swallow their disappointment and sadness in front of the pressure. It is difficult and troubling to work within a workplace when the high-ups are unfair or reluctant and stubborn to listen to the workers.

Different with western management style, this K-Type management consists of top down decision-making, paternalistic leadership, personal loyalty and high mobility of workers (Lee 2012, 184). The organization structure of companies is highly centralized and formalized with authority concentrated in senior levels. In the present context of a Korean organization in which seniority is highly respected in the group (Hofstede, 2001), the power is distributed unequally. A salary man has nothing besides paychecks and promotions. Being in a position of power is a very important goal in business since promotion is as vital as paychecks. A person’s hierarchical status is the most apparent indicator of his/her power within the organization, however, dissimilarities in hierarchical position will hamper social integration of members and decrease willingness to share ideas that may not be accepted by others within the group (Choi 2007, 213). Because subordinates are less likely to contradict their superior in public, they prefer to use a more compromising style in solving interpersonal conflict with their supervisors in a Korean company (Kim 2007, 23). The perceptions of hierarchical culture relate negatively to group working. Senior managers working in organizations that have a strong hierarchy culture were likely to show bureaucratic and rules-oriented approaches.

Bureaucracy defined as a system of organization in which most of the important decisions are made by officials rather than by elected representatives. Top management typically utilizes bureaucratic controls to resolve intergroup conflicts in Korean firms. The top-down decision making system, many operational rules and procedures, and strict hierarchy of authority represent the bureaucratic organization. On the other hand, less specialized and separate tasks show a low level of formality and standardization in the organization (Lee 1987, 75).

As we discussed in class, there are also many hierarchical behaviours at dinner as well as in the office. We understand subordinates try to make conversations sound polite and respectful by using honorifics and talking in a low profile, whereas these behaviours also limit, put down and claim authority over younger generation especially when it comes to Korean office culture demonstrated in Misaeng. Having a dinner party together after working is a common thing in the Korean company. For instance, Sales Team 3 often discusses their work in a restaurant while they are drinking alcohol. It is also the time to enhance the relationship within a group but workers cannot relax vigilance at this point. There are many hierarchical behaviours and drinking etiquette on the wine desk. Things like pouring for others and “one shot” the alcohol are the behaviours subordinates should do to show the respect to high-ups and follow the hierarchy.

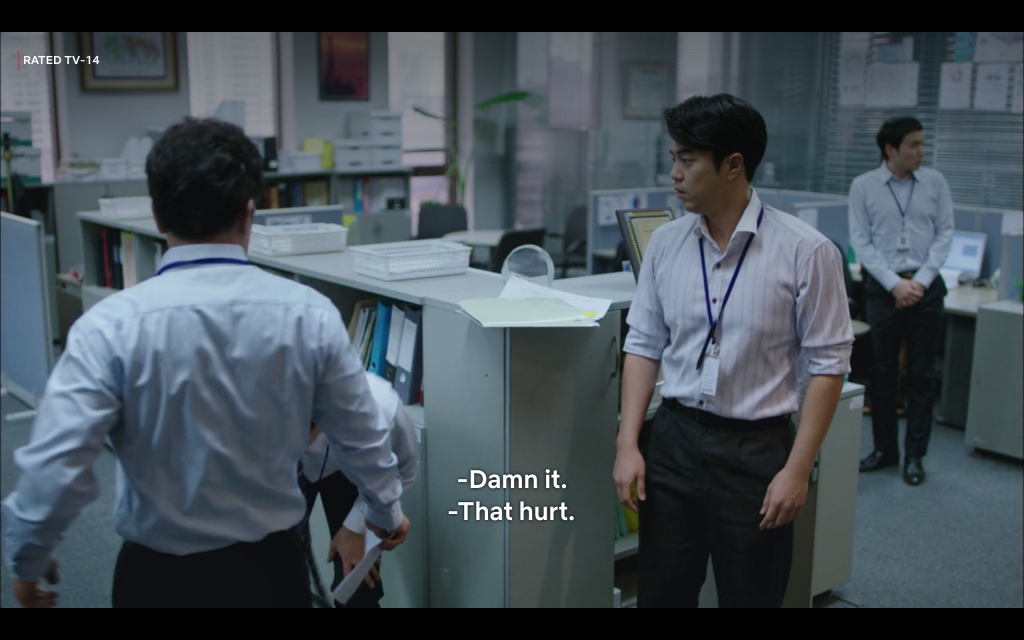

Figure 2 and 3. Manager Ma kicks and hits his subordinate, section chief Jung Hee-Seok, during scolding.

In Misaeng episode 15 and 16 respectively

The drama depicts personal insults by a person who is older and holds a superior position as a common phenomenon in Korean office culture. Sometimes the high-ups even attack subordinates physically during scolding. We can see from Figure 2, Chief Jung gets a kick in the shin by Manager Ma because his subordinate didn’t find the contract at once. This abuse is a one-direction phenomenon as it only goes from the people with higher position to the lower position in the company. Usually subordinates won’t fight back under the huge pressure since those high-ups have the power to promote them or change their career lives. Employees are harmonious in work just to avoid confrontations with their managers. Just as children must repress hostility towards parents, subordinates must repress hostility towards their superiors (Oh 1991, 49). The lack of superior to subordinate obligations has let to dysfunction in some respects. It results in the displacement of hostility downward to the lower ranks in the hierarchy. After a general staff been promoted in a company, it is a large chance he will treat his subordinates the way he been treated before.

In Figure 3, Manager Ma literally shoves the phone into the guys’ chests as he yells at them for not doing their jobs properly, and just as he’s about to poke the phone into Young-yi’s forehead, Chief Jung interrupts and tells Manager Ma to not touch his or his staff’s bodies again. Everyone stands in tense nervousness as Manager Ma silently stares them down and then leaves. Later on, Chief Jung shocked and scared by the way he just confronted Manager Ma while others are trying to comfort and praise him. We can see this reaction as a fight back to the higher authority. There is always a limitation for the tolerance or restraint. Every unfair phenomenon is seen by each subordinate. Hierarchy culture is a unique and species lesson for every Korean to respect people who older than them and who have higher level. However, true respect and deference need to be earned through wise actions and admirable behaviour, not simply given based on a person’s age or position. A harmonious environment is needed for people to keep a good mood and do effective works.

Gender Inequality

The increasing female employment has become one of the most remarkable social transformations in Korea. The sexist issues and the problem of gender stereotypes continue to exist in Korean society for a long time. Respecting gender differences and treating women fairly in the workplace have been increasingly important to accomplish social equity and justice for women, just as Korean mainstream media and pop culture increasingly create misogynist characters in popular media, and display the sexist problems to encouraging audiences to fight against sexist oppression. As a powerful influencer on society, mainstream media has the responsibility to educate audiences the true meaning of gender equality. It is reported that gender, race and age result in either high or low status and competence expectations of a particular individual (Tsui et al. 2002, 899). Given that Korean society has historically been male-dominated and that males have been ascribed with more dignity and social power, gender also signifies a meaningful source of status differentiation among members.

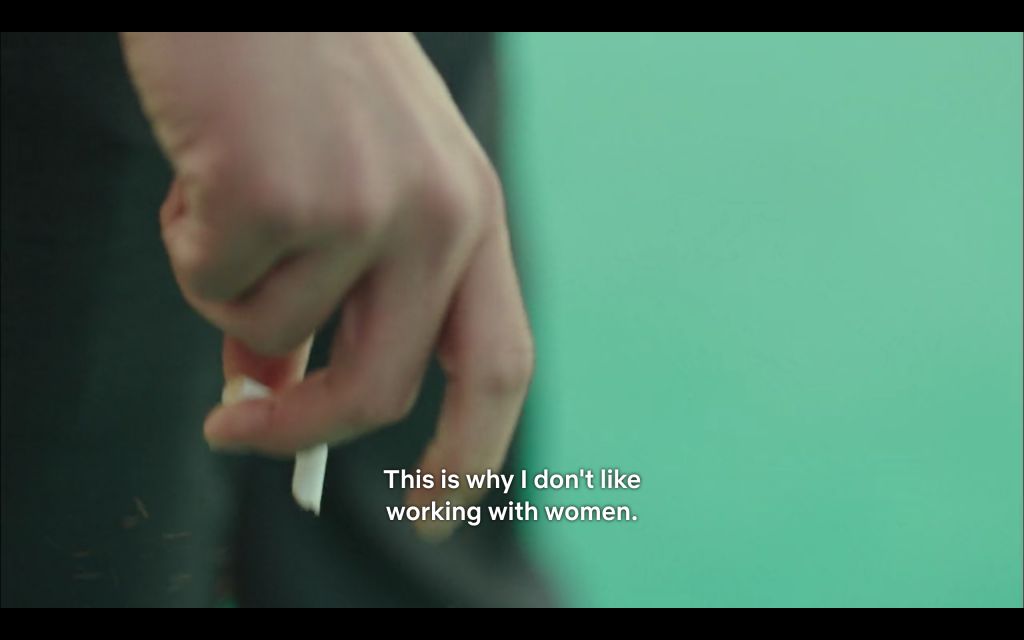

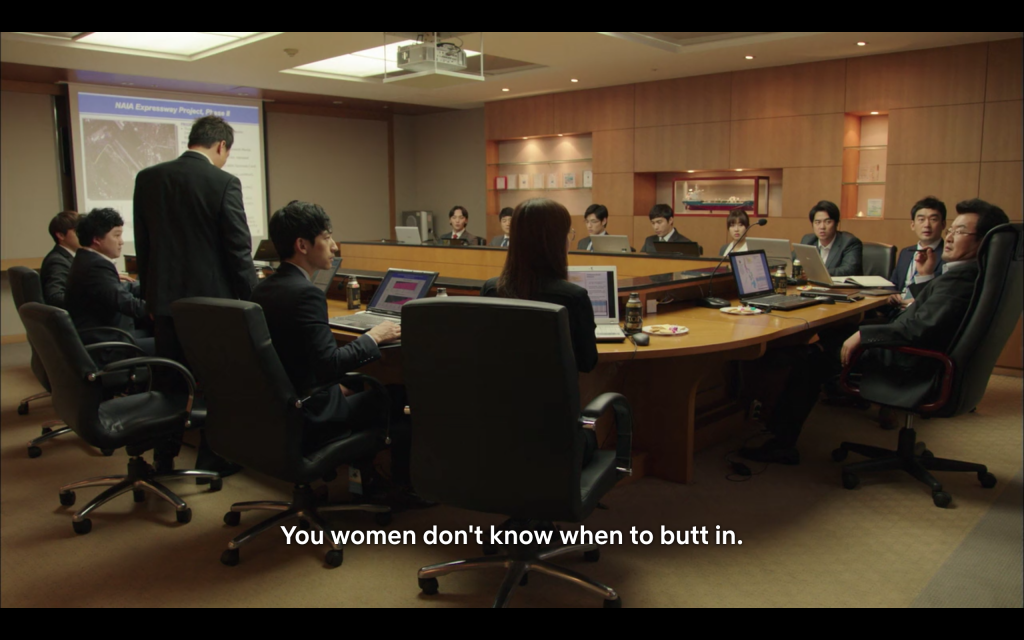

Figure 4. Young-yi manager scolds her and says women have no sense of sacrifice.

Figure 5. Manager Ma orders Ms. Sun to stay put because she is a woman.

Both in Misaeng episode 5

There are two main female characters in Misaeng: Young-yi and Manager Seon. Young-yi represents female newbies in a new company, while Manager Seon represents working moms in Korea. The two of them react differently when both confront circumstances that are unmistakably sexist and misogynistic. We can see misogyny practically everywhere throughout the narrative, from gender discriminative to sexual harassment.

Much of the gender discriminative actions in Misaeng are focused on violent language harassment which are visible to viewers. According to Figure 5, when Manager Ma accuses Chief Oh of embezzlement, Deputy Director Sun tries to placate him, but he tells her that women need to know their boundaries and stop butting in on these discussions. Ms. Sun started to get angry and then left the meeting room after Manager Ma yells at her. In contrast, Figure 4 shows that Young-yi is scolded by her resource team senior for not completing a task assigned to her. The team senior shakes his hand and ashes his cigarette at her feet, complaining that women don’t understand the sacrificial mindset. He condescendingly commands her to apologize, and she does so stoically. In this situation, Young-yi chooses to bear the taunt and abuse this time, as well as every time she follows managers instructions even through those male workers are looking down on her. Two female characters give different reactions to the superiors but both scenes arouse people’s awareness to fight against sexist oppression. Female viewers will get mad and infuriating after watching other women get offended.

As we talk about gender inequality, sexual harassment is another very serious form of employment discrimination.

Mr. Ma: “Why is that sexual harassment? The one who wore plunging neckline is at fault. So did I touch her or even look at her? I asked her why she wore something like that if she’s going to cover it every time she bends over. Is that considered sexual harassment?”

Male workers shake their head sideways to show what he is saying is reasonable.

Mr. Ma: “What I was trying to tell her is for her not to wear something like that.

Male workers nod their head with an awkward smile to show agreement.

Ms. Sun: “‘Even if you leave it be, there’s nothing to look at anyway.’ You also said that.”

Mr. Ma: “That’s true. Is that sexual harassment? (Shouting with a fierce tone of anger) Young-yi, what do you think?”

Young-yi: “If the person being told that feels sexually harassed, I think it is sexual harassment.”

Misaeng Episode 5, 29:43-31:42

Young-yi gives audiences a rational definition of sexual harassment. The criterion and boundary of sexual harassment are often hard to define but it should be decided by the victim. All definitions of sexual harassment include the word “unwanted” and almost all include the concept of power (Maypole 1983, 385). Sexual harassment is the imposition of unwanted sexual requirements on a person within the context of an unequal power relationship. Sexual harassment in the workplace is perpetrated mainly by male supervisors against women and it has been identified as one of the most damaging and ubiquitous barriers to career success and satisfaction for women (Willness 2007, 127).

A large increase in the female employment has become the most noticeable social transformation in Korea since urbanization. Despite the rapid increase, women in employment have not been treated fairly in important personnel procedures and decisions, such as work assignments and promotion. The problem of glass ceiling is often neglected and overlooked in Korean society. Male-oriented cultures and politics may have critical impacts on personnel decisions. The drama also illustrates the impact of Korea’s glass ceiling for career women. This actual problem in society is realistic and is crucially disadvantaging females from getting hired and promoted. To address the issue, the Korean government has passed legislation that promotes representation of women and prohibits discrimination against women in important personnel decisions and procedures. However, the legislation is equivocal and does not provide detailed definitions of gender or opinions to offer additional guidance for managers by clarifying and interpreting the statutory requirements in Korea. The governmental policy to end gender-based discrimination in employment has not only been superficial but also ineffective in correcting gender inequity in the workplaces (Choi 2014, 119). Women’s sex roles, sex stereotypes, and male-oriented organizational culture are the three barriers continually be challenging to women who seek to reach higher positions in the Korean company. One solution would be having more female managers in decision-making positions will be helpful to prompt greater attention to the interests of women and foster women-friendly organizational cultures. More female managers and executives may contribute to reduce sex stereotypic views on women that women are not qualified for leadership roles with decision-making responsibilities (Choi 2014, 119).

While gender equity in employment has been addressed in many different cultures, in Korea there is limited scholarly effort in public administration to understand women’s working conditions and needs in the workplaces (Choi 2014, 119). Misaeng makes a good example in mainstream media and causes wide attention on gender equity issues.

Conclusion

Compared to other traditional Korean dramas, Misaeng uses less romantic storyline and more description about career stories to show audiences a realistic workplace. It uses different storylines to reveal that Korean workplace has an intense and pressured atmosphere due to interpersonal stressors, such as generalized hierarchical behaviour and gender issues, are highly prevalent and significantly linked with Korean workplace. Korea is going through a lot within its pursuit of equality for all. After Misaeng aired in 2014, we wish there will be less interpersonal pressure in the workplace and everyone can focus on their workload peacefully.

Bibliography

Choi, Jin Nam. “Group composition and employee creative behaviour in a Korean electronics company: Distinct effects of relational demography and group diversity.” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 80, no. 2 (2007): 213-234.

Choi, Sungjoo, and Chun-Oh Park. “Glass ceiling in Korean civil service: Analyzing barriers to women’s career advancement in the Korean government.” Public Personnel Management 43, no. 1 (2014): 118-139.

Hofstede, Geert. Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. Sage publications, 2003.

Kim, Tae-Yeol, Chongwei Wang, Mari Kondo, and Tae-Hyun Kim. “Conflict Management Styles: The Differences among the Chinese, Japanese, and Koreans.” International Journal of Conflict Management 18, no. 1 (2007): 23-41.

Lee, Choong Y. “Korean culture and its influence on business practice in South Korea.” The Journal of International Management Studies 7, no. 2 (2012): 184-191.

Lee, Sang M., and Sangjin Yoo. “The K-type management: A driving force of Korean prosperity.” Management International Review (1987): 68-77.

Oh, Tai K. “Understanding managerial values and behaviour among the gang of four: South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Hong Kong.” Journal of Management Development 10, no. 2 (1991): 46-56.

Maypole, Donald E., and Rosemarie Skaine. “Sexual harassment in the workplace.” Social Work 28, no. 5 (1983): 385-390.

Misaeng (also known as: “An Incomplete Life”). Directed by Kim Won Seok. South Korea: Number 3 Pictures, 2014. Netflix.

Tsui, Anne S., Lyman W. Porter, and Terri D. Egan. “When both similarities and dissimilarities matter: Extending the concept of relational demography.” Human relations 55, no. 8 (2002): 899-929.

Willness, Chelsea R., Piers Steel, and Kibeom Lee. “A meta‐analysis of the antecedents and consequences of workplace sexual harassment.” Personnel psychology 60, no. 1 (2007): 127-162.