Synopsis:

[Ep. 18] Manager Oh decides to accept the Director’s proposal, but the team quickly runs into difficulties with the project. Kim Dong-shik and the rest of Sales Team 3 suggest to withdraw, but Manager Oh thinks otherwise as he struggles to find balance in his values and the workplace politics. Han Seok-yool takes matters in his own hands on a delivery company and is suspicious of his Assistant Manager’s actions.

[Ep. 19] Sales Team 3 is uneasy after Geu-rae voices his suspicisions about the Director’s project with Seok (the employee from the Poshin company). The Head Office launches an investigation on Geu-rae’s team and the Director’s involvement with the project. Han Seok-yool continues to investigate Assistant Manager Sung.

There are many ramifications for countries that provide the necessary resources and incentives for its citizens with job security. Reflecting from previous discussions, as well as in the drama: Misaeng 미생 (also called “An Incomplete Life” 아직 살아 있지 못한 자 ) (2014), contemporary Korean society and South Korean (hereafter Koreans) citizens, have led a tough and intense transition for building its ‘brand image’ and reputation it has created today – through its complex history, Korean popular culture, modernization, tourism, etc. However, despite the efforts of restructuring work and progress in Korean society, has also emerged socio-economic pressures on Korean citizens, which are highlighted in the episodes, such as: overworking, workplace bullying, high industrial accidents, high education inflation, gender and status gap, duality in employment rates, financial security, etc. (Lambert & Webster 2010: 596). As a result of Korea’s abrupt restructuring process, has impacted many citizens and families struggle to adapt to these growing changes as mentioned above – as well as issues like, mental health, or “stress and uncertainty,” etc. in society have emerged – to support themselves and the household (Ibid., 596). In this paper, I will look into the struggles of job security in Korean society and how this is represented in episode 18 and 19.

According to the OECD (The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) data collected as of 2015, the trend results show that Korea’s labour compensation per hours worked have slightly increased and decreased over the years since 1999, with a significant drop in 2012; and despite gaining recovery in 2013, labour compensations have continued to drop. This is interesting to take note of, since Misaeng (2014) was currently airing around this period, and the development of the plot shows the discrepancies with issues of corruption that happens around the business politics in major companies, like One International. In one incidence, it is also curious to note that in episode 18 and 19 (or the drama as a whole), the Executive Director or the higher ups, do not mention what specifically are the labour compensations and incentives offered to their employees, other than job promotions. However, what seems to be done under the table and behind closed doors, is the idea of accepting briberies and taking advantage of the business connections to cover up parts of the business contract or deals, which is a common trend as shown throughout the episodes.

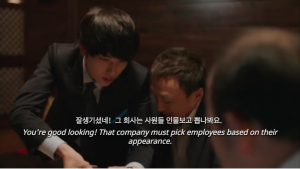

(Misaeng 2014: Ep. 18)

(Misaeng 2014: Ep. 18)

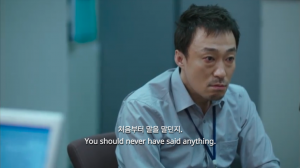

(Misaeng 2014: Ep. 19)

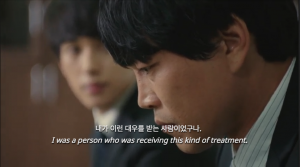

(Misaeng 2014: Ep. 19)

Analyzing the relationship between Manager Oh and Jang Geu-rae in both episode 18 and 19 proves to show an example of job security, especially for temporary workers and permanent workers as well. The OECD shows that the trend report for temporary employment is 20. 6% in Korea for 2017, which is ranked fairly high compared to other countries. This suggests that temporary employment creates both job opportunities and job destruction, which eventually increases unemployment rates in Gyeongjoon Yoo and Changhui Kang’s article (2012: 581). According to Yoo and Kang, they state that Korea implemented a labour reform in 2007, on regulating temporary contracts by shortening the maximum allotted work period on temporary workers from an unspecified length to two years (2012: 579). Manager Oh and the employees around Geu-rae know that if the project with Poshin (Sales Team 3’s business partner that is based in China) goes well, Geu-rae can stand a chance to become a permanent worker at One International. Theoretically, as stated by Yoo and Kang: “under the new regulation, a temporary contract should be either converted into a permanent contract,” or be dismissed within two years after signing the contract with no costs (Ibid., 579). As evident in the episode, this appears to be the case for Geu-rae who faces this reality.

(Misaeng 2014: Ep. 18)

However, the application process is not that easy since “employee conditions in South Korea vary greatly, depending on the type of employment, the size of the company, occupation, etc.” (Jung & Cho 2016: 5). This can be seen in the scene in episode 18, where Geu-rae speaks to his mother on the phone about looking for work during the time he was going to intern (Misaeng 2014: time 1:15:17-1:15:40). With these conditions, this seems to indicate keeping the protection of permanent workers, rather than equal employment protection on the level of employment for all employees (Yoo & Kang 2012: 579).

(Misaeng 2014: Ep. 18)

Although Korea ranks significantly high in working hours, according to the results in the 2017 trend reports from the OECD, a case study shows the stark reality that citizens with low job security, could lead to negative effects and signs of higher risk or exposure to mental health issues, such as depression, suicide, etc. (Kim et al 2017: 668). This can be seen in episode 18, when Ahn Yeong-yi is confronted by her father again to pay off his debts, as viewers see the stern look across her face to escape his grasps; thus, confirming the reality of the financial struggles to support oneself and the conflicts between families that exists for a secure job (Misaeng 2014: time 59:48-1:00:40).

(Misaeng, 2014: Ep. 18)

To conclude, the dual reality of labour force policies that are set-up in Korean society, does not entirely benefit part-time workers, temporary workers, and the self-employed, or female employees, who are applying for or receiving benefits to keep their jobs due to the structures of the labour force market (Jung & Cho 2016: 5-6). Viewers have come to learn the drastic effects and socio-economic measures that define one’s status to succeed in Korean society. One of those factors suggest that obtaining higher education would guarantee financial stability with a qualifying white collar job, but is not always the case when competition and favouritism on certain jobs stratifies a widening gap to attain job security (Kim & Choi 2015: 448, 456-457). As Misaeng (2014) comes to reach its finale, the turning point within these episodes demonstrates the struggles of finding job security in South Korea with temporary work. As the inevitable fate for Geu-rae’s job standing arises – as his colleagues try to find ways for Geu-rae to secure him a permanent job position – it is also a matter of time and further study into the question of creating more diversity and equality with job security for citizens, to find a good work-life balance.

Question(s):

At the beginning of the drama, Geu-rae narrates the quote: “A path is opened to everyone, but not everyone can have that path.” (Misaeng 2014: Ep.1, time 5:53-5:58). What do you think this means after watching these 2 episodes or the stories progress in terms of job security?

What other alternatives could be offered to South Korean society for job security?

In essence of this episode, if you were in Geu-rae’s position, would you accept the challenge (of the project) as a career opportunity to secure a job position in the company or would you likely stay or keep your doors open for something else?

** Photos are screenshots from the drama, no copyright infringement is intended **

Bibliography

Jung, Hanna and Joomo Cho. “Quality of Jobs for Female Workers: A Comparative Study of South Korea and Australia.” Applied Research Quality Life 11 (2016): 1-22.

Kim, Doo Hwan and Yool Choi. “The Irony of the Unchecked Growth of Higher Education in South Korea: Crystallization of Class Cleavages and Intensifying Status Competition.” Development and Society 44, no. 3 (2015): 435-463.

Kim, Min-Seok, Yun-Chul Hong, Ji-Hoo Yook, and Mo-Yeol Kang. “Effects of Perceived Job Insecurity on Depression, Suicide Ideation, and Decline in Self-Rated Health in Korea: A Population-Based Panel Study.” International Archives of Occupational Environmental Health 90 (2017): 663-671.

Lambert, Rob, and Edward Webster. “Searching for Security: Case Studies of the Impact of Work Restructuring on Households in South Korea, South Africa and Australia.” Journal of Industrial Relations 52, no. 5 (2010): 595-611.

Misaeng 미생 (also called 아직 살아 있지 못한 자 “An Incomplete Life”). Directed by Kim Won Seok. South Korea: Number 3 Pictures/tvN, 2014. Streaming video. https://www.viki.com/tv/20812c-incomplete-life?locale=en.

OECD. “Hours worked.” (Indicator). 2018. doi: 10.1787/47be1c78-en (Accessed on 21 June 2018)

—-. “Labour compensation per hour worked.” (Indicator). doi: 10.1787/251ec2da-en (Accessed on 21 June 2018)

—-. “Temporary employment.” (Indicator). doi: 10.1787/75589b8a-en (Accessed on 21 June 2018)

Yoo, Gyeongjoon and Changhui Kang. “The Effect of Protection of Temporary Workers on Employment Levels: Evidence From the 2007 Reform of South Korea.” ILR Review 65, no. 3 (2012): 578-606.