Imaginary Homelands

In “Culture, Globalization, Mediation,” William Mazzarella traces the effects of globalization on anthropology to a shift in the 1990s that initially placed the onus of representing locality back on the informant. This later prompted a greater need for reflexivity, both on the part of the informant and—significantly for Mazzarella—the ethnographer (Mazzarella 2004). Mazzarella aligns this change in perspective with shifting processes of mediation that allow us to view ourselves as a “close distance” (2004:348): viewed at a remove, we can begin to imagine ourselves in new ways, and the world imagines alongside us.

Thus processes of globalization have inspired a “revalorization of the local” (2004:352), a sentiment Mazzarella observes companies and institutions have seized on in a bid to “recuperate the aura of authenticity” (2004:347). This search for authenticity extends to digital media, and as Mazzarella points out, we prefer to imagine this arena as an unfiltered, democratic mode of self-representation rather than acknowledging a mediating presence that “undercuts the romance of authentic, intuitive identification” (2004:348). What happens, then, when a local culture is mediated, by way of the internet, to a global audience—but the locality being represented ceases to exist, except in the minds of its mediators?

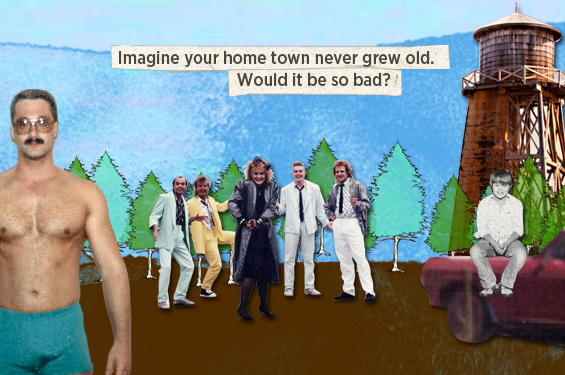

I recently encountered Welcome to Pine Point (www.pinepoint.nfb.ca), an interactive website produced by Michael Simons and Paul Shoebridge, two Vancouver-based creative directors, in association with the National Film Board of Canada. Pine Point was a planned mining town located in the Northwest Territories and at its peak, had a population of 1,200 (Wikipedia). After the mine’s resources were depleted and the site shut down in 1987, the government decided to raze the town completely. The website—part scrapbook, part documentary—is dedicated to remembrances of a place that “was left standing just long enough for a single generation to run through it” (Simons and Shoebridge). The result is a thoroughly engaging, emotionally arresting experience, unlike anything one would expect to have in an online environment. It is the story of a specific time and place, told through a digital interface that incorporates the voices of a handful of the town’s former citizens, photographs, animation, and video. What is striking about these testimonies (a term my boyfriend suggested after watching it, and one which I think is apt) is that in the absence of a physical location to house their memories, the community’s shared remembrances have come to stand in for that which is signified. One of the interview subjects articulates this phenomenon:

You create this fictional community in your head over the course of the years and what it tends to do is erases [sic] a lot of the negative stuff. And then, as you create this over the years, you do end up with a utopia. You think, there was nothing wrong, nothing bad ever happened. But in reality, it was a normal community—bad stuff happened all the time. What we’ve created for our hometown may be the better choice: an online community and the memories I have. I can go back there anytime I want and it hasn’t changed. (Simons and Shoebridge)

Viewed at a distance through this website, Pine Point becomes an exercise in the co-constituitive model of culture and media to which Mazzarella subscribes. The resulting mediation is a “relation of simultaneous self-distancing and self-recognition” (2004:357) where Pine Point is reconstructed and reimagined in a new global medium. In light of globalizing forces that threaten to erase difference, Mazzarella stresses the need to be more reflexive and examine “the places at which we come to be who we are through the detour of something alien to ourselves, the places at which we recognize that difference is at once constitutive of social reproduction and its most intimate enemy” (2004:356). The Pine Point website project celebrates the ephemerality of a specific community’s ethos, but its haunting, intangible qualities are a reminder that processes of globalization were partly responsible for the closure of the Pine Point mines. The localized website circulates as part of a larger discourse on transnational mining corporations and their impact on the surrounding communities. By congregating at a physical and temporal distance to mediate the culture of Pine Point, the documentary’s creators and participants attempt to reproduce a culture that ceases to exist—and in fact, may have never existed the way it does in their minds—and paradoxically achieve a cultural specificity that resonates on a transnational level. Their insistence that this is how it happened—“And who are you to judge?”, the narrative asks—reminds us that we remediate the story they are telling about themselves. As Clifford Geertz says, “We see the lives of others through lenses of our own grinding and […] they look back on ours through ones of their own” (2000:65).

Taken with the evocative storytelling of Pine Point, I posted a link to the site on my Facebook page, adding my own commentary: “Imagined communities, indeed.” Half an hour later (about the amount of time needed to interact with the site), a friend who lives in Victoria, Australia, posted a comment: “That was wonderful.”

Works Cited

Geertz, Clifford

2000 Available Light: Anthropological Reflections on Philosophical Topics. Princeton: Princeton UP.

Mazzarella, William

2004 Culture, Globalization, Mediation. Annual Review of Anthropology 33:345–367.

Simons, Michael and Paul Shoebridge

2011 Welcome to Pine Point. Produced by the National Film Board of Canada. http://www.pinepoint.nfb.ca, accessed Jan. 20, 2011.

Wikipedia

Pine Point, Northwest Territories. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pine_Point,_Northwest_Territories, accessed Jan. 20, 2011.