David Novak argues that “appropriation is a creative act” (2010:42) and suggests that remediation, the “repurposing [of] media for new contexts of use” (2010:41), resonates with the cosmopolitan subject’s capitalism-fuelled sense of alienation. While he notes that the Heavenly Ten Stems’ live performance of the Indian song “Jaan Pehechaan Ho” triggered accusations of cultural imperialism, Novak seemingly sanctions the outcome, valorizing the incident as a watershed moment for “revealing the fantastic aspects of global popular music as a multidirectional social imaginary” (2010:60). Can a similar defense be made of two other examples of media reuse: the Bollywood-inspired ice-dancing performance by Americans at the 2010 Winter Olympics, and Man Ray’s photographs of African art? While the former example was generally embraced for its expression of multiculturalism, the latter is problematic when viewed through a postcolonial, postmodernist lens.

Meryl Davis and Charlie White’s Olympic ice dance performance for the “folk music” round of the competition used music from the 2002 Bollywood film Devdras to complement Bollywood-inspired choreography and costuming (Armour 2010). I was in attendance at this event; the Americans’ performance was well received, both by the judges and the audience, particularly in light of the fact that they followed Oksana Domnina and Maxim Shabalin, the Russian team whose Aboriginal-inspired routine, which did not use traditional music, was almost universally deemed culturally insensitive (suggesting that media reuse would have been less problematic). The Indian response (both in India and in the U.S.) to the Americans’ routine, as characterized in the media, was cultural pride (Armour 2010)—this, despite the fact that Bollywood film music would not generally be characterized as traditional “folk music.” The skaters worked with a former Bollywood dancer and purchased clothing from an Indian store (Associated Press 2010). The knowledge that competitors were required to perform a type of “cultural drag” in a non-traditional setting (the skating rink) leaves one less inclined to fault the performers themselves; that the American duo consulted a cultural “authority” and used elements of “authentic” dress as inspiration helped them to evade the criticism their Russian counterparts faced. Gawker columnist Maureen O’Connor offered an additional explanation: “India, like America, is in the cultural export business, so imitation comes across as flattery instead of mockery.” Bollywood film is already a highly lucrative cultural industry for India; Davis and White are as much the intended consumers as anyone else watching, and the circulation of the film’s music in this internationally televised arena, did not, for many viewers, constitute a commodification of power or transfer of ownership.

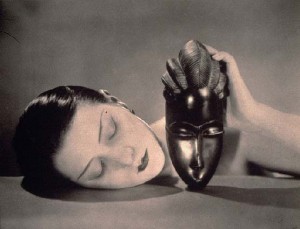

By contrast, the photographs of African art by modernist artist Man Ray, featured recently in an exhibit at the UBC Museum of Anthropology, involve a more complex relation of power. The exhibit explored the influence of Man Ray’s photos—such as “Noire et Blanche,” which depicts a white woman holding a dark-coloured African mask—on elevating African artifacts from ethnographic curiosities to works of art. As part of the avant-garde, artists such as Man Ray sought to expand post-WWI Western conceptions of art and beauty by presenting “primitive” culture in an aesthetically palatable contrast. Today, our postmodern and postcolonial perspectives have us question the commodification of culture inherent in the photographs, as well as the fetishistic nature of their portrayal: dramatic lighting and the use of white female models that reinforced an self/other dichotomy. The decontextualization of the African art is undoubtedly problematic given the power dynamics of colonial history. For its part, the MOA exhibit invited dialogue by allowing visitors to examine the photographs alongside the three-dimensional objects depicted in them.

Having examined these two disparate examples of media reuse that differ in historical context, target audience, medium of expression, and circulation in popular culture vs. high culture, I would suggest that it is extremely difficult—if not impossible—to develop guidelines for assessing what constitutes cultural reappropriation. I will say that I find Novak’s neutralization of the phenomena as a consumer critique or as a celebration of “new subjects within ‘alternative modernities’” (2010:42) to be too pat. If I can draw any lines, it would be these: reuse that attempts to reassign meaning, as in the case of Man Ray, should open discourse rather than sever its connection with the original; reuse that is more tributary in nature should strive for a sense of responsibility to the original to avoid a flattening out of cultural difference.

Works Cited

Armour, Nancy

2010 Davis-White’s Bollywood-style OD a hit in India. Associated Press website, Jan. 5. http://wintergames.ap.org/story.aspx?st=id&id=pf751416f0dc6429ca83c35e6368eb399

Associated Press

2010 Davis, White Set for Upset. ESPN.com, Jan. 23. http://sports.espn.go.com/olympics/winter/2010/figureskating/news/story?id=4851092

Novak, David

2010 Cosmopolitanism, Remediation, and the Ghost World of Bollywood. Cultural Anthropology 25(1): 40–72.

O’Connor, Maureen

2010 More Adventures in Olympic Racial Drag. Gawker.com, Feb. 22. http://gawker.com/#!5476940/more-adventures-in-olympic-racial-drag