The Feminist Gaze of “Amélie”

The protagonist of the French film Le Fabuleux Destin d’Amélie Poulain (“The Fabulous Destiny of Amélie Poulain”), is a shy, quirky Parisian with a fantastical imagination. She is depicted as content with her interior life and self-reliance, but a series of events lead her to seek out greater human connection and eventually pursue a male companion. Throughout the film, Amélie, frequently looks directly into the lens: either that of the film camera (at the viewing audience) or into the lens of a photo booth camera (an important setpiece). This narrative frame-breaking is not out of place in a film is populated by elements of magical realism (for example, people in photographs are able to talk), but it also provides a feminist reversal of the male gaze, the workings of which Laura Mulvey describes in her influential article, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (1975). I argue that Amélie is a feminist film that subverts conventions that would find the woman hemmed in as object of male conquest and pleasure.

The film provides several visual cues that undercut the effect of scopophilia, a Freudian instinct toward “taking other people as objects, subjecting them to a controlling and curious gaze” (Mulvey 1975:835). Early on, the film’s male omniscient narrator intones, “In 48 hours, her life will change forever, but she doesn’t know it yet,” over a shot of Amélie looking defiantly into the lens as if to challenge the notion of destiny, particularly that scripted by a male narrator, a male director (Jean-Pierre Jeunet) and male screenwriters (Jeunet and Guillaume Laurant). We later see Amélie in her bathroom, wearing her nightgown, as she dabs on perfume while watching a news report. She eventually switches the television off, but aims the remote at the lens/audience to do so, ending the scene and disrupting this intrusion into her private feminine ritual.

Following Freud, Mulvey notes that scopophilia taken to the extreme “can become fixated into a perversion, producing obsessive voyeurs and Peeping Toms, whose only sexual satisfaction can come from watching, in an active controlling sense, an objectified other” (1975:835). The diegesis of Amélie contains its share of would-be voyeurs. Joseph, the rejected lover of Gina, is a permanent fixture at the diner where Amélie and Gina work. He dictates into a tape recorder his paranoid perceptions of Gina’s interactions with male customers and his surveillance of the woman-run diner (“4:05. Blatant female conspiracy”).

But Amélie, too, is a Peeping Tom: she observes Dufayel, a frail, reclusive man in her building, at first through the window and then through binoculars. However, her surveillance is used to illustrate her stirrings for deeper human connection, rather than for sexual possession. She reserves this desire for Nino, in whom she senses a kindred spirit. He is an employee at a sex shop/peep show theatre and also works as a skeleton at a local carnival’s house of horrors attraction. As a hobby, he collects discarded identification photographs, appropriating the product of the camera’s gaze for his own fetishistic pleasure. Upon discovering this, Amélie is intrigued and sets out to ensnare him by presenting herself as the object of his gaze: she visits the carnival where in his role as skeleton, he stares at her and clearly yearns to touch her, yet she does not return his gaze at this point. She sets the terms of her pursuit, leaving clues Nino must assemble in order to meet her, including a direction to view her through observation binoculars. When he is within her grasp, she reverses the gaze, watching him from behind a glass at the diner. Her introversion keeps her from speaking to him, but he remains an object of desire.

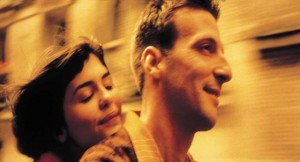

Meanwhile, Duyafel watches Amélie through binoculars and a camera he has trained outside his window, monitoring her slow progress toward love and using the camera to communicate his advice to her to follow her heart. Inspired by Dufayel’s words, Amélie opens her door to Nino, and Dufayel turns off the camera. While Dufayel clearly recognizes the impropriety of his continued surveillance, it could also be argued that this merely validates the power of the male gaze to advance the narrative and “mak[e] things happen” (Grey 2010:838). However, that the film ends with a shot of Amélie looking first into the lens and then with her eyes blissfully closed as she and Nino ride on a motorcycle, suggests otherwise: she has succeeded in her sexual pursuit and by seizing control of her own destiny and desire, she has no further need to engage with those who would try to objectify her.

Works Cited

Film: Amélie (2001: directed by Jean-Pierre Jeunet)

Gray, Gordon

2010 Film Theory. In Cinema: A Visual Anthropology, Pp. 35–73. Oxford, New York: Berg.

Mulvey, Laura

1999 [1975] Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. In Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings. Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen, eds. Pp. 833–844. New York: Oxford University Press.

April 26th, 2011 at 2:26 pm

interesting, well written, makes me go and watch it again…