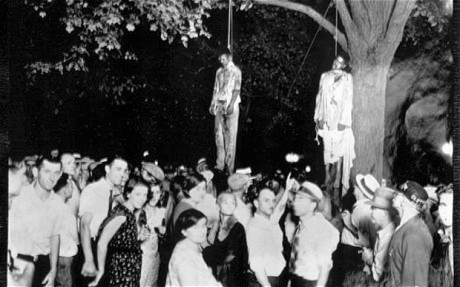

The public spectacle of lynching blacks. Image borrowed from:http://mtwsfh.blogspot.ca/2008/02/1885-1894-more-invasions-more-racism.html

“The aim was to make an example, not only by making people aware that the slightest offence was likely to be punished, but by arousing feelings of terror by the spectacle of power letting its anger fall upon the guilty person” -Michel Foucault in Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (1975/1995, p. 58)

In the beginning of Foucault’s Discipline and Punish (Part 1: chapters 1 & 2), Foucault illustrates the public spectacle of punishment as it was exercised in the punitive city, where precise, hierarchical forms of punishment were commanded down from the highest echelons of the state and displayed for the public. Foucault’s historical example was Damiens, a French citizen who was tortured in public for attempting to assassinate King Louis XV of France. The public execution was quite gruesome, as it involved methodical procedures of drawing and quartering Damien’s body.

Foucault highlights the body of the condemned as the bearer of punishment, a powerless entity that is carved by the state. The act itself, with the body at center stage, is characteristic of a theatrical play, as it requires everything that is needed for a successful play: a theatrical producer, a writer, stage designers, performers, an audience, and of course, the art of choreography. The sequence of blows and incisions carried out by the executioners, the agonized cadences of the condemned, the priest’s comforting prayers of salvation, the success and failures in commanding the horses, and the astonished presence of the public, all exemplify the state’s theatrical production of public execution. The mechanisms of power that are involved in such a production are what Foucault attempts to illustrate with the first two chapters.

However, it is important to understand that Foucault explains these forms of punishment from the punitive city as a historical period that quickly declined with the emergence of more humane laws and practices, mainly brought forth by enlightenment ideals and a growing capitalist political economy. As Foucault states: “It was an important moment. The old partners of the spectacle of punishment, the body and the blood, gave way. A new character came on the scene, masked. It was the end of a certain kind of tragedy; comedy began, with shadow play, faceless voices, impalpable entities. The apparatus of punitive justice must now bite into this bodiless reality” (1975/1995, p. 16).

For Foucault, the late eighteenth century marked the end of the punitive city and its spectacle of punishment through torture and executions, as new forms of punishment based on rehabilitation became the dominant practice of criminal justice. However, in the United States, public executions and techniques of torture did not end in the late eighteenth century, as African-Americans were subjected to terroristic elements of white supremacy that continued well into the twentieth century.

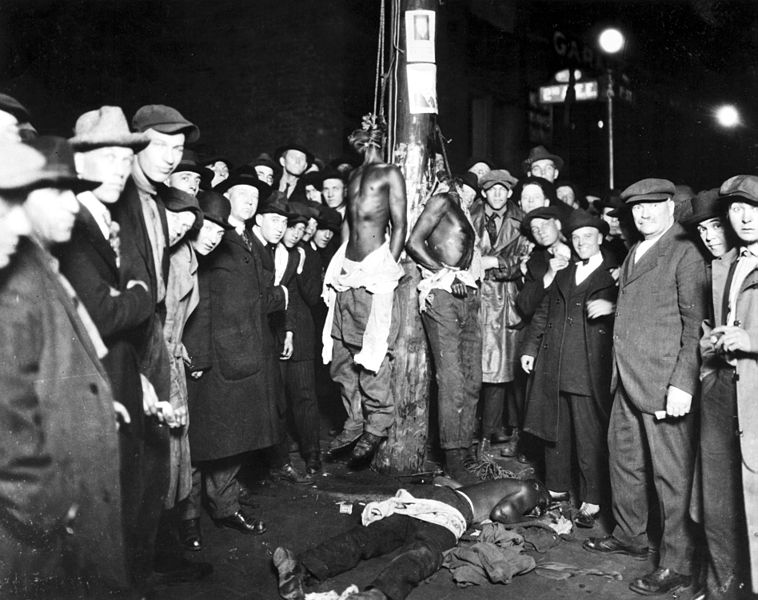

Throughout slavery and Jim Crow laws, thousands of blacks were hung, shot, burned, and castrated, as whites sought to reinforce the racist ideology of white supremacy throughout local communities. While reasons for the lynchings varied, there was one underlying motive: a bitter and racist contempt for blacks and the need to maintain white supremacy. For many of the lynchings, particularly in the South, the community was invited to watch, as black bodies were showcased for public amusement. In some communities, lynchings became a ritual, which often gave whites an incentive to search for blacks, detaining them on charges of vagrancy, being drunk, challenging white authority, or most significant, looking or talking to white women inappropriately. The degree of which whites had justification in lynching blacks was endless, and with a deeply entrenched racist society it was certainly “open season” on African-Americans.

Crowds watch the hanging of three black men in Nebraska (1919). Image borrowed from:http://yeyeolade.wordpress.com/2011/05/02/lynching-in-amerikkka-origin-of-the-word-picnic-is-pick-a-nigger/

In Discipline and Punish, Foucault states: “The public execution is to be understood not only as a judicial, but also as a political ritual. It belongs, even in minor cases, to the ceremonies by which power is manifested” (1975/1995, p. 47). Just what does this statement mean? Well, for Foucault, the power behind the execution, with all its strict choreographed sequences, is more or less a power that functions as an extension of the state. So in the case of Damiens and King Louis XV, the public spectacle of torture and death was necessary for the state to reassert its dominance and authoritative position in society. In other words, the death of Damiens established an equilibrium of order and peace in society, which had been temporarily skewed by the attempted assassination of King Louis XV of France. However, in the United States, there was a form of power that was distinct from the power Foucault illustrates with the punitive city: the power of race.

Although the power structures of race are intrinsically linked with political and state power, the elements of race are nevertheless easily distinguished from all other forms of power, particularly with the malicious fervor found in racial caste systems. In many respects, political power is determined by the power structures of race. With this in mind, there is a sharp contrast between Foucault’s depictions of state power, as exemplified by King Louis XV of France, and the power of white supremacy found in the United States. The most obvious distinction is how Foucault describes public executions as a method of justice distinct to the eighteenth century, and how both the state and public no longer justified these brutal techniques of punishment. Yet, in the United States, the racist fervor of white supremacy continued and operated as an autonomous power structure that was well supported by many local communities.

While I am simply highlighting American history, the point is this: Foucault puts an end to the punitive city towards the end of the eighteenth century, while in the United States, because of the prevalence of race, the public spectacle of lynching blacks continued on for another two hundred years. This historical phenomenon is certainly worth mentioning, as it locates Foucault’s depiction of the punitive city within the confines of America’s troubled history, and allows North American readers to fully grasp his concepts with modern examples that are closer to home.

*Video: Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IscrQnhg6l8