Whites against integration. Image borrowed from:http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Little_Rock_integration_protest.jpg

“The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line” -W.E.B. Du Bois in The Souls of Black Folk (1903/2009, p. 16)

In the chapter “Panopticism,” Foucault illustrates the plague society where a “strict social partitioning” effectively quarantined the sick to prevent the spread of disease (1975/1995, p. 198). Under these conditions, state bureaucracies were deployed to reinforce social boundaries using methods of surveillance, supervision, confinement, and inspection. As Foucault states: “The plague-stricken town, traversed throughout with hierarchy, surveillance, observation, writing; the town immobilized by the functioning of an extensive power that bears in a distinct way over all individual bodies–this is the utopia of the perfectly governed city” (p. 198). While Foucault illustrates the plague society as the blueprint for modern methods of punishment through containment, the plague-stricken town as a quarantined populous of undesirable individuals can also serve as a tool for understanding America’s dark history of racial segregation.

Throughout slavery, the era of Jim Crow, and even throughout the second half of the twenty-first century, African-Americans were considered inferior to whites and deemed a race that was not worthy of civil liberties and political rights. As a result, racial prejudices firmly established a racial caste system that divided a nation based on racial identity, a division that still haunts America to this day. After the Reconstruction Amendments failed to grant African-Americans their freedom, African-Americans slipped into the vicious laws of Jim and Jane Crow: a legal commitment to racial segregation. Resembling Foucault’s model of the plague society, African-Americans were quarantined into American inner cities, while whites surveyed black activity from the outside. Today, geographical boundaries based on race are still a contending issue in American society, particularly when it comes to wealth distribution, health, education, crime, and voting rights.

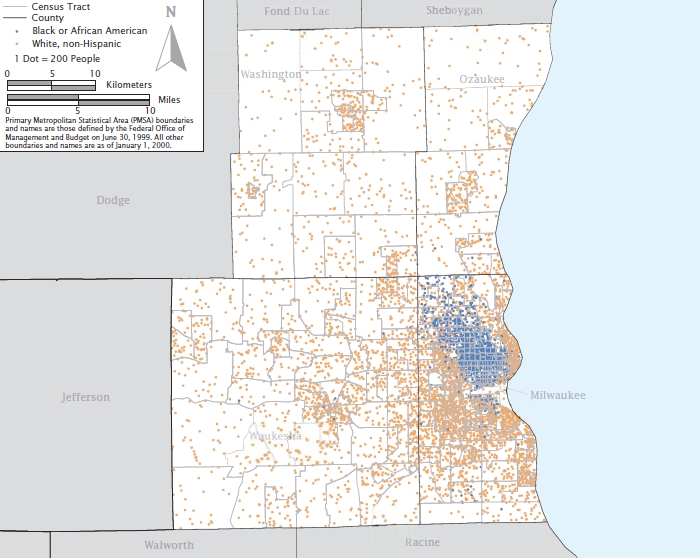

Milwaukee as of 2000. Image borrowed from: http://en.wikipedia.org/ wiki/Racial_segregation_in_the_United_States

The quality of life in the United States continues to be racially segregated, with major American inner cities and rural Southern counties dominated by blacks having the largest concentration of poverty. According to the United States Census Bureau Current Population Report, in 2004, “whites had a household net worth of $534,000 compared to $101,400 for blacks” (as cited in Dyson, 2008, p. 96). Furthermore, as Michael Eric Dyson states: “Many more black children than white children live in concentrated poverty, where the majority of people who live around them are just as destitute. For instance, while only 25% of poor white children in Chicago lived in high-poverty neighborhoods, more than 90% of poor black children found themselves in the slums” (p. 103). When it comes to education, Dyson suggests racial segregation is just as prevalent: “White students typically attend schools where less than 20% of the student body comes from races other than their own. By comparison, black and brown students go to schools composed of 53-55% of their own race. In some cases, the numbers are substantially higher; more than a third of black and Latino students attend schools with a 90-100% minority population” (p. 104).

Foucault’s description of the plague society, where those diseased are socially partitioned, can be attested by the African-American experience throughout their history in America as individuals who have historically led the nation in social ills and have been confined to their own communities. While racial segregation in America is no longer legal, the social implications of the color-line have an immense impact on America’s race relations, particularly with disproportionate rates of black inmates, and of course, the racial boundaries between whites and blacks throughout American cities.

*Video: Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five on the plague-stricken town, otherwise known as the inner city.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O4o8TeqKhgY