Entrance to Auschwitz (http://northernbullets.wordpress.com/2013/05/07/let-auschwitz-die/)

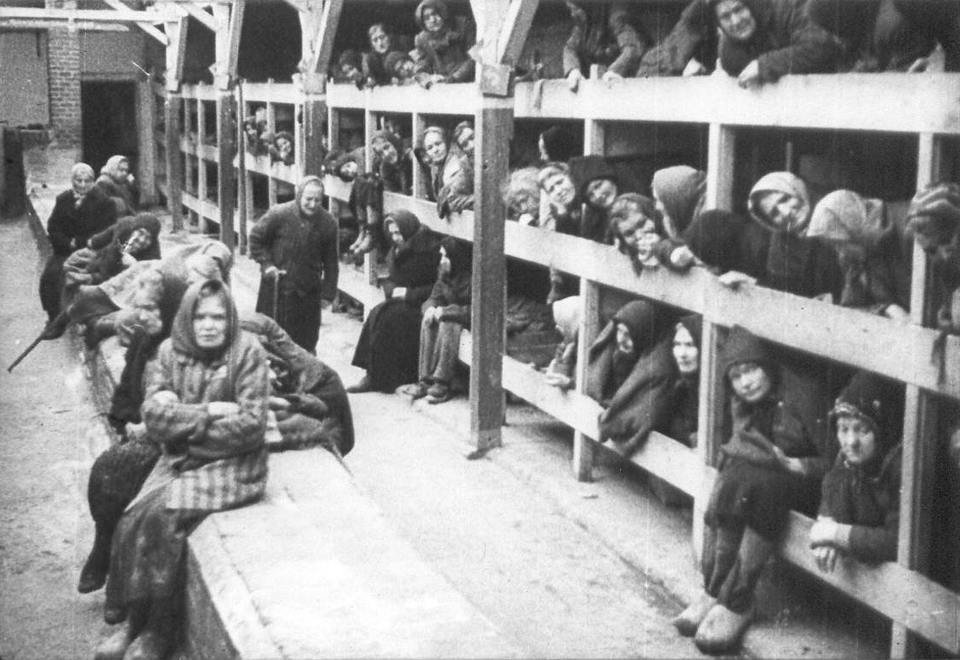

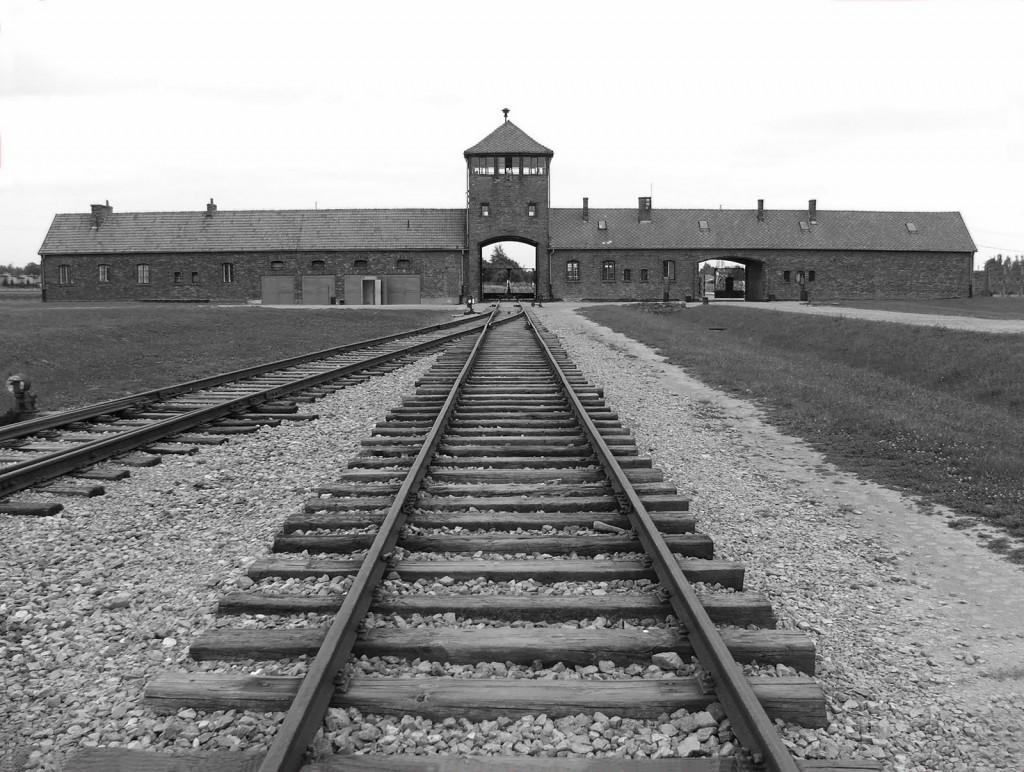

As I think more deeply about Chute’s stress on “bearing witness” (93) when talking about the aim of Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis in her article “The Texture of Retracting in Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis” (http://www.jstor.org/stable/27649737), I am reminded of an experience I went through that also allowed me to bear witness to an historical event: visiting the Auschwitz Nazi concentration camp in Poland. Chute talks about how the representation of memory and testimony through the graphic novel form “makes the snaking lines of history forcefully legible” (93), which is what I also experienced while at the concentration camps. She relates this statement to the political and ethical work of narrative and the traumas shown visually in the comics, allowing these themes and historical events to present themselves directly to the audience. This immediately reminded me of how I felt when I visited Auschwitz and saw, with my own eyes, the dirty, cramped, smelly living conditions of the Jewish prisoners, the long train tracks where they were brought into the camps, stuffed in the train cars like cattle, and the rows upon rows of electric fencing surrounding the wooden bunkers and concrete ovens where they burned the bodies. I remember seeing the piles of shoes, clothing and suitcases piled up, each displaying a deeply personal aspect, taken from the prisoners as they arrived. There was even a mountain of cut hair, shaved from the heads of the Jews when they arrived to prevent the spread of lice. I remember walking through underground concrete “showers” where families were sent thinking they were simply going to be cleaned before entering the camp, but where they were in fact sprayed with poisonous gas, murdered en masse because they were thought too weak to work. I saw torture devices and photos of hundreds and hundreds of starved men, women and children, barely alive or dead and piled on top of each other. I read letters from husbands to wives, saying goodbye and wishing the best for their families, and letters describing the terrible conditions, with barely any food and surrounded by senseless violence. I watched video interviews of concentration camp survivors describing their awful experiences, for which they will forever be scarred.

Sleeping Quarters (http://michaelatures.wordpress.com/author/michaelatures/page/2/)

Railway at Entrance (It still looks exactly like this today) http://adventuresinpoznan.blogspot.ca/2011/05/auschwitz.html

This deeply emotional and visual experience based around remembrance made vivid connections for me while reading Persepolis, especially in the way that visuals and words are used in describing trauma (or, as Chute words it, the “hybridity” (93) of a graphic novel). In both experiences (reading Persepolis and visiting the Auschwitz museum), I heard from the people who struggled through these awful events firsthand, and I also experienced them visually, adding to the emotional effect and the sense of “bearing witness.”

One of the main purposes of turning the Auschwitz concentration camp into a museum is to encourage remembrance and discourage ignorance, as well as serving to promote “not forgetting” (Chute 94). This was also Chute’s take on Satrapi’s reason for writing Persepolis. Part of her conceptual summary of the graphic novel could even be used to describe the Auschwitz museum. She writes, “Persepolis is about the ethical, verbal and visual practice of “not forgetting” and about the political confluence of the everyday and the historical…” ( 94). As I was looking online for recent articles on Auschwitz, I came across this one: (http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/aug/25/auschwitz-first-world-war-tourism-teaching) which raises the ethical question of, basically, how far we should go with acting as witnesses and remembering. The article brings up the topic of stag party organizers that include a visit to Auschwitz in their program as a “lads must-see,” and describes it as “a top bonding experience,” similar to other, more trivial events they do, such as “running with bulls and oil wrestling” (Bennett). People are starting to worry that these traumatic historical events, such as the Holocaust, are starting to be “trivialized” and becoming only tourist attractions for people to gawk at, forget about and then grab a beer. They have even allowed the Harlem Shake to be filmed in the Auschwitz concentration camp. I also remember that two days after I visited museum, I read in the news that the famous Arbeit Macht Frei (“Work Makes You Free” in German) sign (see picture at beginning of post) at the entrance of the camp was stolen by two young men. These multiple examples of disrespect are proof that people today are not taking these distressing historical events seriously. They don’t care about remembering or being a witness. The article goes on to talk about steps that are being taken to “fight ignorance” and hopefully teach the next generation to learn, remember, and care. The article also goes on to talk about how studies have shown that visual experiences are more impacting and effective on emotions than simply hearing or reading. This, I feel, is why graphic novels, and specifically in this case, Persepolis, are a much more effective way of allowing readers to bear witness, remember so as to heal and work to prevent recurrences, and feel the emotions of others who struggled through those difficult times.