The Growth and Transformation Plan (GTP) is a national strategy to coordinate growth polices across government agencies in Ethiopia. The first 5-year plan was released in 2010 and was replaced by the second plan (GTP II) in 2016, effective until 2020 (European Commission, 2016). The overarching goal of both plans is to reach middle-income status by 2025 –driven by resource-led growth. Within both plans, electricity generation and universal access are foundational pillars, and renewable energy is considered an especially critical “priority sector” – both on and off-grid (Gordon, 2018). The first GTP set a goal of increasing generation capacity from 2 GW to 4 GW over the five-year plan. While this goal was not achieved, the second plan (GTP II) is considerably more ambitious, with a goal of reaching 17 GW of generating capacity by 2020.

Reaching the target of 17 GW in the next two years is incredibly unlikely, considering the total installed generating capacity of Ethiopia is currently 4.5 GW in 2018. Despite this shortcoming, the government has several large electricity projects planned, including one of the largest hydropower projects in the world – the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam; the largest (planned) geothermal project in Africa – the Corbetti project; and five new wind farms. These new projects aim to bring total installed generating capacity to 5 GW by 2020 (Gordon, 2018).

For the remaining two years under the GTP II it is unlikely that this focus on large, utility-scale generating projects will change. This is largely a function of the centralized structure of the government – described below in Section 1.2. It should also be noted that this policy strategy aims to limit development of fossil-fuel electricity generation; however, Gordon (2018) Identified an urgency to diversity the mix of electricity sources as Ethiopia is currently over-dependent on large hydropower and with increasing drought frequency in recent times, relying on generation capacity from this single source is expected to become less reliable in the future (Norton Rose Fulbright, 2016).

PRIMARY ENERGY

Primary energy use is supplied through national resources with very little being imported. These inland resources are dominated by biomass fuels for cooking and domestic heating which is driving deforestation in the country. The agricultural sector, and the coffee industry in particular, produces substantial bio-waste and currently this material is under-utilized. As of 2011 the domestic production of bio-waste from this sector was estimated to be 38 million tonnes annually, with only 6 million tonnes being utilized (Ministry of Water & Energy, 2013).

SECONDARY ENERGY

There are three main sources of secondary energy in Ethiopia: refined petroleum, bioethanol and electricity. Of the total 37.3 TWh of refined petroleum, diesel fuel is the main product (20.1 TWh) – used as a transport fuel but also for both public and private thermal generation in areas where access to the electricity grid is limited. Gasoline use is only 13% (2.7TWh) to that of diesel. Kerosene use is also a large component (at 8.8 TWh) and is mainly used for lighting and jet fuels – as Ethiopian Airlines is currently the largest airline in Africa (IEA, 2014). Bioethanol is produced in six sugar factories in Ethiopia, with twelve more facilities planned to be operational by 2020. As of 2016, bioethanol production accounted for 0.1% of global production, and is used to blend gasoline (gasohol E10) and for cookstoves for domestic use (Ethiopian Sugar Corp, 2018). Electricity is on course to replace refined petroleum as the main energy carrier. The amount of petroleum growth is increasing (107% increase, 2004-2013), but the rate of electricity growth is increasing faster (243% increase, 2004-2013) (IEA, 2014). Among Sub-Saharan countries, Ethiopia ranked the second highest in installed generation capacity at 4.5 GW (as of 2018), and has a relatively advanced infrastructure network, as compared to other countries on the continent (Gordon, 2018). Further, the World Bank found that in 2018 approximately 80% of the population of Ethiopia was living within proximity to medium voltage transmission lines (World Bank, 2018).

The majority of electricity production is delivered via large hydro projects (see Figure 1) and the World Bank estimates that large hydro will remain the primary source of baseload electricity in the near future. The Growth and Transformation Plan II (2015-2020) endeavours to supplement this baseload with new geothermal projects and intermittent sources of renewable electricity to meet peak demand (Gordon, 2018).

Figure 1 – Ethiopia Electricity Generation by Fuel Type

FUTURE PROJECTIONS

Based on assessments completed by the Ministry of Water and Energy, Ethiopia has identified 45 GW of economically feasible hydroelectric potential, 1,350 GW from wind, 5.2 GW from solar photovoltaic and 7 GW from large geothermal (Ministry of Water and Energy, 2013). Assuming even a high degree of error in these calculations, potential for expansion of renewable electricity in Ethiopia is substantial.

Measuring the total length of transmission lines in country is a rough way to estimate electricity penetration over time. In 2015 Ethiopia had approximately 10,869 kms of installed transmission lines, however this is expected to increase substantially by 2020, as the government (through the National Electrification Program) plans to build 114 new transmission substations to service 13,540 kms of new transmission line (Norton Rose Fulbright, 2016).

The government of Ethiopia has also crafted plans to increase electricity export to neighboring countries in an effort to increase regional connectivity. As a member of the East Africa Power Pool, Ethiopia already provides electricity to Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda, Sudan and Djibouti (East African Power Pool, 2018). This plan provides added incentive for investors and increases the market potential for electricity projects in Ethiopia, though at this time the system favours larger on-grid projects. This plan will also provide the government with an external source of revenue generation and will increase the share of renewable generation of the region, as Ethiopia is set to export electricity from large hydroelectric generation.

ENERGY POLICY

Ethiopia emerged from a communist-style government in 1991 and has been making considerable progress toward democratization of its governance systems. Progress has been slow and there remain legacy effects of socialism in Ethiopia today which, despite their drawbacks, in many ways work to centralize and stream-line decision-making power. The economic, political and business sectors have thus evolved together in an interconnected, economy-first approach which has often been compared to that of China (Gordon, 2018) with the logic that top-down resource-led growth will drive social development. This centralization/coordination of decision-making power has been recognized as the driver of a phenomenal double-digit growth trajectory for over a decade and led to the third-highest rate of public investment in the world. However, this growth in public investment has come at the cost of stagnant private-sector investment – sitting at the sixth-lowest rate of private investment in the world – as of 2016. As a result, state-run enterprises and companies associated with the ruling party have dominated the sector (World Bank, 2016).

While the government may prefer to utilize public investment in the electricity sector, it acknowledges the limitations (especially capital limitations) of such a plan and in recent years has taken steps to diversify investment flows to include international investors. In 2017 the government signed its first Independent Power Producer (IPP) contract for a geothermal electricity project (Bloomberg, 2018). Building on this turning point, earlier this year the government began talks to partially privatize the state owned Ethiopian Electric Power (EEP) (Reuters, 2018). These developments indicate a serious, coordinated effort toward growth and transformation of the electricity sector in Ethiopia.

An on-going policy challenge involves tackling the disaggregated structure of rural electrification agencies in the country. There are currently at least six agencies overseeing the electricity sector and these agencies often have overlapping or worse, contradictory policies. Many communities are not serviced by the central grid and instead rely on privately financed micro and off-grid projects to generate electricity; however, investors of these projects need to coordinate with these agencies yet face increasing uncertainty in whether the policy changes being enacted will lead to competition with the large state-run grid once these areas become serviced (ODI, 2016).

REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT

While the policy changes from the GTP II have led to encouraging results along many metrics, regulations have not matched pace and remain sparse in many areas. For example, there have been no polices to support mechanisms like feed-in-tariffs or net metering commonly used to add certainty to pricing for producers to sell electricity to the central grid. Further, regulations are currently geared toward development of large-scale projects with little attention to distributed generation (Reuters, 2018). These gaps in regulation add to the already uncertain policy regime of the electricity sector and work to undermine predictability of private investment, especially for small-scale or community projects. According to the REN21 report, there are currently 128 countries with policies to support feed-in-tariffs or net metering (REN21, 2018) however Ethiopia will remain uncompetitive if it does not move toward support of these tools.

Despite these regulatory challenges, the government has demonstrated sustained support through incentives and expedited access to decision makers – especially for investors of on-grid renewable electricity projects, relative to neighboring countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Investors in off-grid projects have not received the same support (Gordon, 2018). In line with the GTP II goal of achieving universal access by 2025, the government has set a target of 35% of electricity to be generated by off-grid sources – acknowledging that these private projects are important for rural electrification. While it is noteworthy to acknowledge this, there has been a lack of coordinated effort to support this goal and the central, top-down approach of the government has continued to dominate the sector, stifling investment and innovation in off-grid generation (Gordon, 2018).

ASSOCIATED RISKS

Ethiopia has a relatively unique land allocation and ownership system, as all land is government owned. While this reduces access challenges and asset risk, it also has many negative consequences, both social and environmental (Gordon, 2018). The corruption and security risks in Ethiopia are less than neighboring countries, providing a stable and improving climate for foreign investment, relative to other developing jurisdictions (Plummer, 2012). Reputational risk exists in the form of criticism for benefitting from the consequences of controversial land policies including forced relocation with inadequate compensation (Human Rights Watch, 2012). Other risks exist in the electricity sector, including currency shortages and weak labour rights, however, these risks are much smaller than those mentioned above (US Department of State,2017).

SUMMARY OF THE SECTOR

While there has been movement toward liberalization of the electricity market in Ethiopia, public sector dominance is expected to remain strong. This feature has led to a reliance on large scale generation projects and despite encouraging progress resulting from the two Growth and Transformation Plans, there remains a dearth of regulatory guidance in the sector which creates uncertainty for investors and increases negotiation cost and time. Underdevelopment of the regulation is partially offset by favourable government incentives and improvements to the risk landscape of infrastructure projects in Ethiopia, compared to other sub-Saharan countries; however, off-grid and distributed projects continue to face substantial obstacles as the incentives are mainly targeted toward large generating projects, supressing investment and innovation in small to medium alternative sources. For these reasons, many of the commercially-proven mechanisms and technologies used in other developing jurisdictions may not be replicable in Ethiopia. Factoring in all of these unique features of the Ethiopian electricity sector, it becomes increasingly clear that large, utility-scale projects are favoured to private off-grid and distributed projects, and this trend is expected to continue. This finding is quite unique on the continent of Africa, where many countries build a policy environment conducive to private small to medium projects while large generating projects face a greater risk portfolio and often a lack of transmission infrastructure capacity.

PROJECTED DEVELOPMENT IN A SUSTAINABLE MANNER

Public-Private Partnerships to Finance and Deliver Low GHG Electricity

Given the predisposition of the Ethiopian government to maintain central public control over the electricity sector, any strategy to move the system toward a low GHG trajectory must account for this pre-condition. As illustrated in Figure 2, infrastructure investment needed in 10 African countries (including Ethiopia) to meet the Sustainable Development Goal of universal access to electricity will be approximately 5% of GDP (GIH, 2018). The challenge the Ethiopian government faces with the strategy of central control is access to the necessary upfront capital to invest in expensive infrastructure projects with long payback periods.

Figure 2 – Infrastructure Investment Needs in 10 African Countries (Source: GIH, 2018)

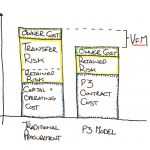

The electricity sector in Ethiopia has been operated exclusively as a state monopoly, controlled by the Ethiopian Electric Power Corporation (EEPCo) – with the exception of off-grid electricity transmission and supply which was opened to private investors in 2003 (Kifle, 2018). Private participation (when allowed) has been limited to design and construction, with turnover of the project to the owner (government) upon completion. For example, the 120 MW Ashegoda wind farm was constructed in 2013 by a concessional loan from a French Development Agency and, upon completion, it was turned over to EEPCo as the full owner and operator (Power Technology, 2013). This procurement method, often called a public-private-partnership (or P3) is frequently used in developed countries like Canada, the UK and Australia. The motivation for this model is the cost savings realized by allocating the risks associated with project construction, operation and maintenance to the actor best suited to bear the risk, including transfer of some of these risks to the private sector partner. There is a market incentive for the private partner to reduce costs and capitalize on the innovation of the private sector.

The full value of a P3 is only realized when it includes life-cycle operation and maintenance (O&M) over a set time period. The government contracts a private firm to design, build, operate and maintain the infrastructure project and pays back the up-front construction cost plus O&M in scheduled payments amortized over the life of the contract. The contract also has performance indicators to ensure that the infrastructure is adequately maintained, and the service provided to the public is consistent. In Ethiopia, private partnerships have been limited to design and construction only, so to capitalize on the full value of this procurement model it is essential that the government relinquish control over O&M (but not necessarily ownership) of future projects and allow deeper participation and realize cost savings.

While this model has been shown to provide significant value for money in developed countries, experiences from its deployment in developing countries yields mixed results. One of the pre-requisites of a successful P3 is an established and functional legal and regulatory framework. Given the limitations described above (plus the fact that private investment in the electricity sector is a new feature) clear regulation, law and policy will need to be built to support increased private participation (World Bank, 2017). Once these obstacles are overcome, there is great opportunity to unleash the potential of private sector investment in the electricity sector.

Transport Fuels

Urban congestion and pollution are serious problems in the capital city of Addis Ababa, with the majority of commuters using private minibuses – largely fueled by diesel. One of the pillars of the GTP II is managing rapid urban growth and progress has been made in Addis in the last decade, with expanding bus services and the construction of a light rail system in 2015 (Zerihun et al., 2016). Like the electricity sector, these services require additional and rapid investment. With the considerable renewable energy potential of the country (described in Section 1.1.4), and an existing stable transmission network, there is an opportunity to scale up these services to displace petroleum consumption transport within the urban area and build a low GHG system. As described in Section 2.1, private finance can also be leveraged for funding these projects using the P3 procurement model (including system operation and maintenance).

The global share of renewable energy in transport consumption is slowly increasing to approximately 3% today (World Bank, 2018b). While the cost of ultra-low emission vehicles (ULEVs – including electric and hybrid) are declining globally, they remain much too high for the average Ethiopian. Additionally, considering the poor state of road infrastructure in many areas, larger 4-wheel drive vehicles are preferred (and indeed needed) as compact cars are unable to maneuver over much of the terrain. As the cost of ULEV technologies continue to decrease, it is likely the technology will extend to larger vehicles better suited for the environment of Ethiopia. In order to realize the true value of these technologies, government support is needed both in developing charging stations and incentives to purchase these vehicles, but more importantly, road infrastructure improvement is needed to facilitate a greater range of vehicle use.

Outside of Addis Ababa, road infrastructure is much less developed with many roads impassable at times of the year and a lack of interconnectivity across the regions. Given the existing infrastructure and local knowledge of bioethanol production from sugar factories, plus the underutilized 32 million tonnes of bio-waste from coffee production, there is great potential to open the industry to private finance to further develop biodiesel for rural transport.

REPORT SUMMARY

Ethiopia has considerable resource potential to develop domestic, large-scale, dispatchable and renewable electricity. While there has been movement toward liberalization of the electricity market, public sector dominance is expected to remain strong. To finance an energy transition to a low GHG-trajectory while rapidly expanding services, the government would benefit from leveraging private-sector investment and innovation through the use of the public-private partnership model. This procurement model is ideally suited to develop the electricity sector, but is also appropriate for the transport sector – both for public transit in urban areas as well as biofuel production facilities to support rural transport. Recent changes in the government suggest political will to change and adopt new technologies and processes is strong, but the main barriers to realize these changes are access to finance (both government and individual capacity), existing corruption and accountability of decision-makers, and behavioural change.

LITERATURE CITED:

Bloomberg (2018). Ethiopian Geothermal Is Private Equity’s Next $4-Billion Bet. Available from: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-02-05/ethiopian-geothermal-is-private-equity-s-next-4-billion-bet [Accessed December 8, 2018]

Eastern Africa Power Pool (2018). Website homepage. Available from: http://eappool.org/ [Accessed November 28, 2018]

Ethiopian Sugar Corporation (2018). Ethiopian Sugar Industry Profile. Available from: http://ethiopiansugar.com/index.php/en/factories [Accessed December 4, 2018]

European Commission (2016). Growth and Transformation Plan II (GTP II). EuropeAid Resilience Building in Ethiopia (RESET), International Cooperation and Development. Available from: https://europa.eu/capacity4dev/resilience_ethiopia/document/growth-and-transformation-plan-ii-gtp-ii-201516-201920[Access on December 2, 2018]

Global Infrastructure Hub (2018). Global Infrastructure Outlook: Infrastructure Investment Need in the Compact with African Countries. Global Infrastructure Hub/Oxford Economics. A G20 Initiative

Gordon. E. (2018). The Politics of Renewable Energy in East Africa. University of Oxford, Institute for Energy Studies. OIES Paper No. EL 29.

Human Rights Watch (2012). Ethiopia: Forced Relocations Bring Hunger, Hardship. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/news/2012/01/16/ethiopia-forced-relocations-bring-hunger-hardship [Accessed December 7, 2018]

IEA (2014). IEA Key World Energy Statistics. Available from: https://www.iea.org/statistics/kwes/ [Accessed on December 4, 2018]

Kifle. L. (2018). The Legal Basis for Power Purchase Agreements in Ethiopia. Mehrteab Leul & Associates, Available from: https://www.mehrteableul.com/resource/blog/item/27- the-legal-basis-for-power-purchase-agreements-in-ethiopia.html[Accessed December 7, 2018]

Ministry of Water and Energy (2013). Ethiopia’s Renewable Energy Power Potential and Development Opportunities. Government of Ethiopia, Ministry of Water and Energy.

Norton Rose Fulbright (2016). Investing in the Ethiopia Electricity Sector: Ten Things to Know. Available from: https://www.insideafricalaw.com/publications/ethiopia-investing-in-the-african-electricity-sector-ten-things-to-know [Accessed on November 25, 2018]

ODI (2016). Accelerating Access to Electricity in Africa with off-grid Solar: Off-grid Solar Country Briefing: Ethiopia. Country Study, January 2016. Available from: https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/10247.pdf[Accessed December 8, 2018]

Plummer. J. (2012). Diagnosing Corruption in Ethiopia: Perceptions, Realities, and the Way Forward for Key Sectors. Directions in Development – Public Sector Governance, Washington DC: World Bank.

Power Technology (2013). EEPCO Begins Operations of 120MW Ashegoda Wind Farm in Ethiopia. Available from: https://www.power-technology.com/uncategorised/newseepco-begins-operations-of-120mw-ashegoda-wind-farm-in-ethiopia/ [Accessed December 4, 2018]

REN21 (2018). Chapter 2: Policy Landscape. Global Status Report, 2018. Available from: http://www.ren21.net/gsr-2018/chapters/chapter_02/chapter_02/ [Accessed November 28, 2018]

Reuters (2018). Ethiopia Loosens Throttle on Many key Sectors, but Privatization Still far off. Available from: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-ethiopia-privatisation/ethiopia-loosens-throttle-on-many-key-sectors-but-privatization-still-far-off-idUSKCN1J21QV [Accessed December 1, 2018]

Stein. C. (2018), Worsening Ethiopian Drought Threatens to end Nomadic Lifestyle. PhysOrg, Available from: https://phys.org/news/2018-02-worsening- ethiopian-drought-threatens-nomadic.html [Accessed December 1, 2018]

US Department of State (2017). Ethiopia 2017 Human Rights Report. Available from: https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/277243.pdf [Accessed December 7, 2018]

World Bank (2016). Ethiopia: Priorities for Ending Extreme Poverty and Promoting Shared Prosperity. Available from: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/913611468185379056/pdf/100592-REVISED-P154064-PUBLIC-Ethiopia-SCD- March-30-2016-web.pdf [Accessed December 8, 2018]

World Bank (2017). Linking-Up: Public-Private Partnerships in Power Transmission in Africa. The World Bank/International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Washington DC.

World Bank (2018). Ethiopia’s Transformational Approach to Universal Electrification. Available from: http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2018/03/08/ethiopias-transformational-approach-to-universal-electrification[Accessed November 28, 2018]

World Bank (2018b). Tracking SDG7: The Energy Progress Report 2018. The World Bank/International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Washington DC.

Zerihun. A, Wakaiga. J, & Kibret. H (2016). African Economic Outlook – Ethiopia 2016. United Nations Development Programme, OECD, AfDB.