What is a change agent?

What are some of the reasons that change is required in organizations?

Traditional change management versus change through “positive deviance”:

When you think of deviance, this may be what comes to mind:

Positive deviance is similar, but instead of the difference offending people, it’s uplifting or pleasing. The key point is that positive deviance is uncommon.

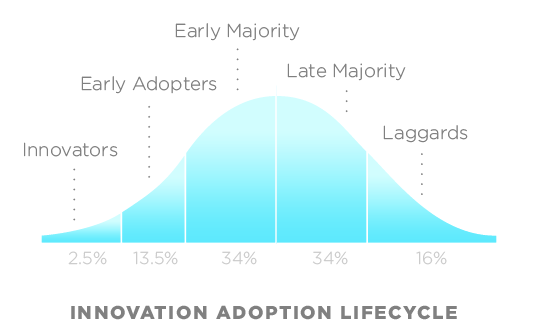

Groups of people respond to technological change differently, and this applies to other types of change as well: Innovators, Early Adopters, Early Majority, Late Majority and Laggards.

Source: Everett Rogers Technology Adoption Lifecycle

Traditional change management utilizes authority to implement change. Why is this far from ideal? (think of how you feel when someone in power tells you to do something you don’t necessarily want to do, or didn’t think to do).

Authority can be effective, even if it’s not ideal: organizations often seek out the causes of problems, then hire experts or import “best-of-breed” practices. This traditional change management is sometimes effective when applied using authority. But only one-third of change projects actually lead to meaningful, long-term improvements!

That indicates authority is only gets you so far, and that Positive Deviance (or other methods that promote people to “buy-in” to change) is the better method to make change. This applies to your family lives, politics, and most other areas in society: you persuade people by nudging them, yet letting them feel in control.

Article from Harvard Business Review: https://hbr.org/2005/05/your-companys-secret-change-agents

How did we address the high dropout rates in Argentina’s rural elementary schools? A workshop on positive deviance sponsored by the World Bank brought together two dozen teachers and principals. They shared a strong suspicion that the nation’s Ministry of Education was trying to implicate them in the high dropout rates and deflect attention from the ministry’s accountability for a woefully underfunded education system. Although 86% of children in Argentina completed elementary education, only 56% of children in the rural province of Misiones did so.

Imagine the setting: a stark cafeteria with concrete floors and steel chairs. The teachers and principals are seated, with their arms folded across their chests. Their body language speaks volumes: “OK, dazzle us with your expertise. This problem involves a whole bunch of things we can’t control. We’re angry. We haven’t been paid in six months. We don’t want to be here.” Blame for the dropout problem lay elsewhere, in lazy students, uninterested parents, and lousy facilities.

The atmosphere changed when workshop participants turned their attention to the question of whether any schools plagued by the same constraints had a better track record. This reframing was reinforced by dropout statistics for all 120 schools in the Misiones district. Working in small groups, the educators found plenty of schools clustered near the median. But they were flabbergasted to discover that one school had retained 100% of its pupils through sixth grade and that ten had retained nearly 90%. “How,” they asked themselves, “do these schools retain so many students?” After all, their teachers presumably hadn’t been paid either. The mood shifted from self-righteous anger to surprise and curiosity.

The workshop participants visited the high-retention schools and discovered that the differentiating factor had little to do with what was happening in the classroom. The teachers there were negotiating “learning contracts” with rural parents before the beginning of each school year. In effect, the teachers were enrolling illiterate parents as partners in their children’s education. As the children learned to read, add, and subtract, they could help their parents take advantage of government subsidies and compute the amount earned from crops or owed at the village store. With parents as partners, students showed up at school and did their assignments. The teachers and principals who had participated in the workshop began negotiating similar contracts with families of at-risk children. One year later, dropout rates in Misiones had reportedly decreased by half.

Thus: Creating change is more than telling people what to do. Remember: “Every action has an equal and opposite reaction. In organizations, that reaction comes in the form of avoidance, resistance, and exceptionalism thinking”. We as leaders are the guides, we make people feel safe and comfortable with new practices and provide them the incentive the implement change.

Complete the assignment here: