Where are the women in conflict? (pol318)

Trigger warning: rape and gendered violence

It is clear to see that women are disproportionately affected by conflict, and that women experience conflict very differently to men. Women are the targets of rape as a war crime, to the extent that 94% of displaced households in Sierra Leonne have experienced sexual violence. Women are forced to marry or to be ‘comfort women‘ – a term which exists as evidence of the efforts to normalise and legitimise sexual slavery in times of conflict. Women are under-represented in the armed forces, and the contributions that they are typically expected to make in conflict zones (providing shelter, acting as couriers, donating money, etc) are considered secondary to the contributions of men. These are facts, they are real things that happen to real people. As such, it would not be untrue or misleading to use such facts and stories in the media, or to inform aid policies or education programs.

However, at a certain point such efforts to address the suffering of women in conflict go too far, and act to further victimise and homogenise women. There appear to be two tasks at hand to the feminist international relations scholar, to improve the lived experiences of women on the ground in conflict, and to empower women to participate more in the peace-keeping process. Are these two goals in conflict? Is the idea of ’empowering’ a person or group of people problematic, as it is predicated on the binary distinction between those with power and those without? This blog will explore these issues, and show that it is possible to address the problematic lived reality of many women in conflict without necessarily homogenising and victimising those women.

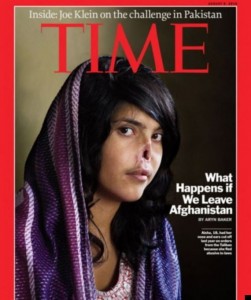

Depictions of women in conflict in the media can be hugely problematic and contribute enormously to the victimisation and homogenisation of women in conflict. The headlines above are examples of this, and depict individual women’s experiences as exemplary of the shared female experience. Adorned with captions such as ‘what happens if we leave Afghanistan’, ”…Manchester can help’, and ‘Gaddafi on the run with 40 virgins’ only serve to reinforce the message that these images and the suffering they tell of are representative of a more widely shared, or even universal, experience. Furthermore, these headlines bring with them remnants of a colonial-era salvation complex, and imply that the women in question are in need of rescuing. The assumption then is that as it is women in the Global South who are being victimised, it is men from the Global North who are best positioned to do the rescuing. The center headline is particularly problematic, as the 40 women in question were actually highly trained guards of Gaddafi, and yet the headline chose to portray them as victims rather than to discuss their rational and willing involvement in the conflict.

Campaigns to ’empower’ women share a key feature with the media’s victimising representation of women in conflict; their focus on the usual powerlessness of the women. Both aim to better the female experience of conflict, either by bringing the help of other powerful figures or by encouraging women in conflict to be strong and powerful. However despite this noble goal, the reliance on the ‘truth’ of the ordinary powerlessness of women in conflict is problematic and acts contrary to feminist goals. Rosie the Riveter is the most significant example of this, and has been critiqued not only for implying that in order to be powerful women must adopt typically masculine traits, but also for failing to recognise the already existing power of women in everyday life.

Cynthia Enloe challenges this assumption and discusses women’s power in everyday conflict scenarios; their power as consumers, as workers, wives, and in other everyday roles. She provides the example of a woman’s rights activist in Cairo (below) who painted her protest placard in both English and Arabic, so that her feminist political statement could be seen throughout the English speaking world as well as the Arabic one.

The challenge at hand for feminist global politics scholars (and the media) is to genuinely appreciate and counter the suffering experienced by many women in conflict, without homogenising all women in conflict to a group of passive victims. We know they are not this.

The challenge at hand for feminist global politics scholars (and the media) is to genuinely appreciate and counter the suffering experienced by many women in conflict, without homogenising all women in conflict to a group of passive victims. We know they are not this.

So how should we go about such a campaign to re-conceptualise the view of women in conflict? My first recommendation is simple and fundamental. Enough with ‘representing’ and ‘giving a voice to’ women in conflict. They do not need representation, they already are enough. They do not need a voice, we simply need to listen. An easy and important place to do this is in peace negotiations, where women are hugely under-represented. Of all of the peace treaties, ever signed, women make up only four percent of the signatories. Those peace agreements which do include women are 64% more likely to succeed than those without. It seems only logical that in order for the female experience of conflict to be considered, women must be fairly represented in the peace making and peace keeping process.

South Sudanese peace talks, with a notable absence of women. Photograph: Carl De Souza/AFP/Getty Images

Overall we must seek to find a balance between recognising both the genuine suffering experienced by many women in conflict and the power of these same women. The best policies are those which combine a recognition of both, such as the greater inclusion of women in the peace-making process.